A History of the Crusades (36 page)

Read A History of the Crusades Online

Authors: Jonathan Riley-Smith

PLATE

15 Crusader’s vigil. A romanticized image of a lone crusader by the German artist Carl Friedrich Lcssing.

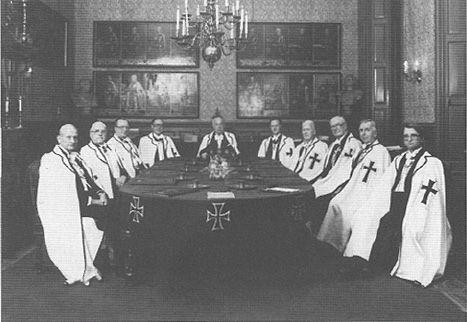

PLATE

16 The only surviving Teutonic knights. Members of the Protestant Bailiwick of Utrecht of the Teutonic Order in chapter. The portraits on the wall behind them arc of their chief commanders who, until recently, were painted in armour.

from pious idealists and refugees from Palestine to prosecute the jihad against the Latin settlements. Leading civilian intellectuals, like al-Qadi al-Fadil and Imad al-Din al-Isfahani, both of whom worked in Saladin’s chancery, incessantly nagged their master, exhorting him to cease fighting against neighbouring Muslims and to turn his armies against the infidel. Al-Qadi al-Fadil and his subordinates were to turn the chancery into a major instrument of propaganda for Saladin, and, in letters dispatched all over the Muslim world, they presented Saladin’s activities as having one ultimate goal, the destruction of the Latin principalities. When partisans of the house of Zangi and other enemies of Saladin attacked him as a usurper and as a nepotist bent on feathering his family’s nest, Saladin’s supporters were able to point to his prosecution of the jihad as something which legitimized his assumption of power. Even so, Saladin was not really very active in the field against the Christians until 1183, after Zangid Aleppo had recognized his supremacy.

Although the armies that Saladin led against the Latin principalities were formally dedicated to the jihad, they were not composed of

ghazi

s. Instead, Saladin’s army, like those of Zangi and Nur al-Din, was primarily composed of Turkish and Kurdish professional soldiers. Most of the officers, or emirs, received an

iqta

, an allocation of tax revenue fixed upon a designated village, estate, or industrial enterprise, which they collected for themselves and in return for which they performed military service. Despite being the recipients of

iqta

, they also expected handouts on campaign. In addition Mamluks, or slave soldiers, formed an important part of Saladin’s élite force, as they did of almost every medieval Muslim army. Saladin and his contemporaries also recruited mercenaries, and the Seljuks in Anatolia even made use of Frankish mercenaries. Finally, the numbers of Saladin’s armies on campaign were swelled out by tribal contingents of bedouins and Turkomans who fought as light cavalry auxiliaries in expectation of booty.

The élite Turkish troops were experts in the use of the composite recurved bow made of layers of horn and sinew and commonly about a metre in length when unstrung. Like the English longbow, the Turkish bow could only be handled by someone who had been trained and who had developed the necessary muscles. Unlike the English longbow, it was an offensive cavalry weapon and it had more penetrating power and an even longer target range than the longbow. However, the mass of bedouin and Turkoman auxiliaries used simpler bows, whose arrows had much less force, and hence those accounts of the English crusaders marching towards Arsuf in 1191, so covered with arrows that they looked like hedgehogs, even though they were more or less unscathed. Muslim troops in close combat generally made use of a light lance, javelin, or sword. Although most men were protected only by leather armour—if that—the emirs and Mamluks in lamellar armour or mail were as heavily protected as their knightly opponents. With the exception of the introduction of the counterweight mangonel as a launcher of projectiles for siege purposes, there were no significant innovations in Muslim military technology in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Kitab al-It‘ibar

(‘The Book of Learning by Example’) sheds an interesting light on encounters between Muslims and Christians on and off the battlefield. Its aristocratic author, Usamah ibn Munqidh, was born in Shayzar in northern Syria in 1095 and died in 1188. He was almost 90 when he wrote his treatise on how divinely ordained fate determines everything, especially the length of a man’s life. Since most of the examples (

‘ibrat

) are taken from Usamah’s own life, the book has the appearance of an autobiography. Viewed as autobiography it is however an extremely gappy and evasive piece of work and it presents a wilfully fragmentary account of his numerous dealings with the Franks. In fact, during the early 1140s Usamah and his patron, Mu‘in al-Din Unur, the general who controlled Damascus, were in regular communication with King Fulk and both visited the

kingdom of Jerusalem on diplomatic business. But business was often mixed with pleasure and, for all his ritual cursing of the Franks, Usamah went hunting with them and he had plenty of opportunities to get to know them socially.

According to Usamah the ‘Franks (may Allah render them helpless!) possess none of the virtues of men except courage’. But this was the virtue that Usamah himself valued above all others, and, in his remarkably balanced account of the customs of the Franks, he is at pains to point to both positive and negative aspects. On the one hand, some Frankish medical procedures are stupid and dangerous; on the other hand, some of their cures work remarkably well. On the one hand, the Frankish judicial procedure of trial by combat is grotesque and absurd; on the other hand, Usamah himself received justice from a Frankish court. On the one hand, some Franks who have newly arrived in the Holy Land behave like barbarous bullies; on the other hand, there are Franks who are Usamah’s friends and who have a real understanding of Islam.

While Usamah chose to stress the many times he had encountered the Franks in hand-to-hand combat, his book is singularly free of any reference to jihad. In part this may reflect retrospective embarassment about his diplomatic dealings with the Franks, but it is also the case that Usamah was, like the rest of the Banu Munqidh, a Shi‘ite Muslim and therefore he had no belief in the special religious validity of a jihad waged under the leadership of a usurping warlord like Saladin.

Incidentally, quite a number of Usamah’s contemporaries, eyewitnesses of the crusades, also wrote autobiographies, which we only know about from quotations in the works of others. ‘Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi (1161/2–1231/2), an Iraqi physician, wrote one such book. Had it survived, it might have been even more interesting than Usamah’s autobiography, for ‘Abd al-Latif, an exceptionally intelligent man who led an interesting life, visited Saladin during the siege at Acre and then later at Jerusalem after the peace with the Richard. ‘Abd al-Latif also wrote a refutation of alchemy, in which he discusses the alchemists’ belief that the Elixir was to be found in the eyeballs of young men. ‘Abd al-Latif remembered being present at the aftermath of one of the battles

between the crusaders and the Muslims and seeing scavenging alchemists moving from corpse to corpse on the bloody field and gouging out the eyeballs of the dead infidel.

In his own times Usamah was famous not as an autobiographer, but as a poet. Although he had studied the Qur‘an with care, his moral values were only drawn in part from the Qur‘an and both the code of conduct he subscribed to and the language in which he described his battles with the Franks and others owed at least as much to the traditions of the pre-Islamic poetry of the nomadic Arabs of the Hijaz. In this respect, Usamah was no different from many of the leading protagonists in the Muslim counter-crusade. The council of advisers around Saladin in the 1170s and 1180s included some of the most distinguished writers of the twelfth century. Imad al-Din al-Isfahani, who worked in Saladin’s chancery, was not only a panegyric historian, but also one of the most famous poets of his age. Al-Qadi al-Fadil, who headed Saladin’s chancery, was similarly a poet. He was also a crucially influential innovator in Arabic prose style and his metaphor-laden, ornate, and bombastic prose style was to be imitated by Arabic writers for centuries to come.

Usamah was said to know by heart over 20,000 verses of pre-Islamic poetry. Usamah’s mnemonic powers were exceptional. But even Saladin, a Kurdish military adventurer, was nevertheless steeped in Arabic literature. Not only did Saladin carry an anthology of Usamah’s poetry about with him, he had also memorized the whole of Abu Tammam’s

Hamasa

, and he delighted in reciting from it. In the

Hamasa

(‘Courage’), Abu Tammam (806?–845/6) had collected bedouin poems from the pre-Islamic period and presented them to his readers as a guide to good conduct. In the Ayyubid period ‘people used to learn it by heart and not bother to have it on their shelves’. According to Abu Tammam, ‘The sword is truer than what is told in books: In its edge is the separation between truth and falsehood.’ The poems he had selected celebrated traditional Arab values, especially courage, manliness, and generosity.

More generally the genres, images, metaphors, and emotional postures pioneered by the pre-Islamic poets helped to dictate the forms of the poetry commemorating defeat and victory in the war against the crusaders and indeed to form the self-image of the élite of the Muslim warriors. Thus tropes developed for boasting about hand-to-hand combat and petty successes in camel raiding in seventh-century Arabia were revived and re-applied to a Holy War fought by ethnically mixed, semi-professional warriors in Syria and Egypt. Saladin’s kinsmen and successors shared his tastes and quite a few of them wrote poetry themselves. Al-Salih Ayyub, the last great Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt (1240–9) employed and was advised by two of the greatest poets of the late Middle Ages, Baha al-Din Zuhayr and Ibn Matruh.

Muslim and Frankish military aristocrats were capable of enjoying each other’s company and might go hunting together. There was also a lot of trade between Muslim and Christian and, in particular, merchants passed backwards and forwards between Damascus and the Christian port of Acre. The traveller Ibn Jubayr observed that ‘the soldiers occupied themselves in their war, while the people remained at peace’. However, though there were numerous contacts between Muslims and Christians, there was little cultural interchange. Proximity did not necessarily encourage understanding. According to the

Bahr al-Fava

‘

id

, the books of foreigners were not worth reading. Also, according to the

Bahr

, ‘anyone who believes that his God came out of a woman’s privates is quite mad; he should not be spoken to, and he has neither intelligence nor faith.’

Although Usamah could not speak French, it is clear from his memoirs that several Franks could speak Arabic. They learned the language for utilitarian purposes. Rainald of Châtillon, the Lord of Kerak of Moab, spoke Arabic and worked closely with the local bedouin in the Transjordan. Rainald of Sidon not only knew Arabic, but he employed an Arab scholar to comment on books in that language. However, no Arab books were translated into

Latin or French in the Latin East, and the Arabs for their part did not interest themselves in western literature. King Amalric employed an Arab doctor, Abu Sulayman Dawud, whom he had brought back from Egypt some time in the 1160s, and this doctor was to treat his leper son, Baldwin. Far more common though was the Muslim use of native Christian doctors. Speculations about the transmission from East to West, via the Latin East, of such things as the pointed arch, heraldic blazons, sexual techniques, cookery recipes, and so forth remain just speculations. Muslim and Christian élites in the Near East admired each other’s religious fanaticism and warrior-like qualities. They had no interest in each other’s scholarship or art. The important cultural interchanges had taken place earlier and elsewhere. Arabic learning was mostly transmitted to Christendom via Spain, Sicily, and Byzantium.

Saladin occupied Aleppo in 1183 and Mayyafariqin in 1185 and he received the nominal overlordship of Mosul in 1186. Only then did he embark on his greatest offensive against the kingdom of Jerusalem. In June 1187 he crossed the Jordan with an army of perhaps 30,000, of which 12,000 were regular cavalry. Some of the remainder were

mutawwiun

, civilian volunteers for the jihad, and Muslim chroniclers noted the role that these volunteers had, performing such tasks as setting light to the grass in advance of the Christian army. Saladin may have been hoping to capture the castle of Tiberias. He was probably not expecting to encounter King Guy of Jerusalem’s army in battle and he does not seem to have made advance preparations to take advantage of the sensational victory he did win at Hattin. Most of the distinguished Christians taken in the battle were eventually ransomed, but Sufi mystics in Saladin’s entourage were granted the privilege of beheading the captured Templars and Hospitallers.

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Saladin moved swiftly to occupy a series of weakly defended places on the coast and elsewhere, before turning against Jerusalem, the surrender

of which he received on 2 October. Saladin had failed to take the great port of Tyre and this would later serve as an important base for the Third Crusade. In a conversation a couple of years after Hattin, as they were riding towards Acre, Saladin told his admiring biographer, Baha al-Din ibn Shaddad, of his dream for the future: ‘When by God’s help not a Frank is left on this coast, I mean to divide my territories, and to charge [my successors] with my last commands; then, having taken leave of them, I will sail on this sea to its islands in pursuit of them, until there shall not remain on the face of this earth one unbeliever in God, or I will die in the attempt.’ However Saladin and his advisers failed to anticipate that the fall of Jerusalem to the Muslims would result in the preaching of yet another great crusade in the West. In the meantime, Saladin’s chancery officials wrote to the caliph and other Muslim rulers. Their letters boasted of the capture of ‘the brother shrine of Mecca from captivity’ and insinuated that Saladin’s earlier wars against his Muslim neighbours could now be seen to be justified in that they had enforced unity in service of the jihad.