A History of the Crusades-Vol 1 (16 page)

From Walter Nicetas must have learnt that Peter

was not far behind, with a far larger company. He therefore moved up to

Belgrade to meet him and made contact with the Hungarian governor of Semlin.

Peter left Cologne on about 20 April. The

Germans at first had mocked at his preaching; but by now many thousands had

joined him, till his followers probably numbered close on 20,000 men and women.

Other Germans, fired by his enthusiasm, planned to follow later, under

Gottschalk and Count Emich of Leisingen. From Cologne Peter took the usual road

up the Rhine and the Neckar to the Danube. When they reached the Danube, some

of his company decided to travel by boat down the river; but Peter and his main

body marched by the road running south of Lake Ferto and entered Hungary at

Oedenburg. Peter himself rode on his donkey, and the German knights on

horseback, while lumbering wagons carried such stores as he possessed and the

chest of money that he had collected for the journey. But the vast majority

travelled on foot. Where the roads were good they managed to cover twenty-five

miles a day.

King Coloman received Peter’s emissaries with

the same benevolence that he had shown to Walter, warning them only that any

attempt to pillage would be punished. The army moved peaceably through Hungary

during late May and early June. At some point, probably near Karlovci, it was

rejoined by the detachments that had travelled by boat. On 20 June it reached

Semlin.

There its troubles began. What actually

happened is obscure. It seems that the governor, who was a Ghuzz Turk in

origin, was alarmed by the size of the army. Together with his colleague across

the frontier he attempted to tighten up police regulations. Peter’s army was

suspicious. It heard rumours of the sufferings of Walter’s men; it feared that

the two governors were plotting against it; and it was shocked by the sight of

the arms of Walter’s sixteen miscreants still hanging on the city walls. But

all might have been well had not a dispute arisen over the sale of a pair of

shoes. This led to a riot, which turned into a pitched battle. Probably against

Peter’s wishes, his men, led by Geoffrey Burel, attacked the town and succeeded

in storming the citadel. Four thousand Hungarians were killed and a large store

of provisions captured. Then, terrified of the vengeance of the Hungarian king,

they made all haste to cross the river Save.

Peter Enters the

Empire

They took all the wood that they could collect

from the houses, with which to build themselves rafts. Nicetas, watching

anxiously from Belgrade, tried to control the crossing of the river, and to

oblige them to use one ford only. His troops were mainly composed of Petcheneg

mercenaries, men that could be trusted to obey his orders blindly. They were

sent in barges to prevent any crossing except at the proper place. He himself,

recognizing that he had insufficient troops for dealing with such a horde, retired

back to Nish, where the military headquarters of the province were placed. On

his departure the inhabitants of Belgrade deserted the town and took to the

mountains.

On 26 June Peter’s army forced its way across

the Save. When the Petchenegs tried to restrict them to one passage, they were

attacked. Several of the boats were sunk and the soldiers aboard captured and

put to death. The army entered Belgrade and set fire to it, after a wholesale

pillage. Then it marched on for seven days through the forests and arrived at

Nish on 3 July. Peter sent at once to Nicetas to ask for supplies of food.

Nicetas had informed Constantinople of Peter’s

approach, and was awaiting the officials and military escort that were coming

to convoy the westerners on to the capital. He had a large garrison at Nish;

and he had strengthened it by recruiting locally additional Petcheneg and

Hungarian mercenaries. But he probably could not spare any men to act as Peter’s

escort until the troops from Constantinople should meet him. On the other hand

it was impracticable and dangerous to allow so vast a company to linger long at

Nish. Peter was requested therefore to provide hostages while food was

collected for his men and then to move on as soon as possible. All went well at

first. Geoffrey Burel and Walter of Breteuil were handed over as hostages. The

local inhabitants not only allowed the Crusaders to acquire the supplies that

they needed, but many of them gave alms to the poorer pilgrims. Some even asked

to join the pilgrimage.

Peter s Arrival

at Constantinople

Next morning the Crusaders started out along

the road to Sofia. As they were leaving the town some Germans who had

quarrelled with a townsman on the previous night wantonly set fire to a group

of mills by the river. Hearing of this, Nicetas sent troops to attack the

rearguard and to take some prisoners whom he could hold as hostages. Peter was

riding his donkey about a mile ahead and knew nothing of all this till a man

called Lambert ran up from the rear to tell him. He hurried back to interview

Nicetas and to arrange for the ransom of the captives. But while they were

conferring, rumours of fighting and of treachery spread round the army. A

company of hotheads thereupon turned and assailed the fortifications of the

town. The garrison drove them off and counterattacked; then while Peter, who

had gone to restrain his men, tried to re-establish contact with Nicetas,

another group insisted upon renewing the attack. Nicetas therefore let all his

forces loose on the Crusaders, who were completely routed and scattered. Many

of them were slain; many were captured, men, women and children, and spent the

rest of their days in captivity in the neighbourhood. Amongst other things

Peter lost his money-chest. Peter himself, with Rainald of Breis and Walter of

Breteuil and about five hundred men, fled up a mountain-side, believing that

they alone survived. But next morning seven thousand others caught them up; and

they continued on the road. At the deserted town of Bela Palanka they paused to

gather the local harvest, as they had no food left. There many more stragglers

joined them. When they continued on their march they found that a quarter of

their company had been lost.

They reached Sofia on 12 July. There they met

the envoys and the escort, sent from Constantinople with orders to keep them

fully supplied and to see that they never delayed anywhere for more than three

days. Thenceforward their journey passed smoothly. The local population was

friendly. At Philippopolis the Greeks were so deeply moved by the stories of

their suffering that they freely gave them money, horses and mules. Two days

outside Adrianople more envoys greeted Peter with a gracious message from the

Emperor. It was decided that the expedition should be forgiven for its crimes,

as it had been already sufficiently punished. Peter wept with joy at the favour

shown him by so great a potentate.

The Emperor’s kindly interest did not cease

when the Crusaders arrived at Constantinople on 1 August. He was curious to see

its leader; and Peter was summoned to an audience at the court, where he was

given money and good advice. To Alexius’s experienced eye the expedition was

not impressive. He feared that if it crossed into Asia it would soon be

destroyed by the Turks. But its indiscipline obliged him to move it as soon as

possible from the neighbourhood of Constantinople. The westerners committed

endless thefts. They broke into the palaces and villas in the suburbs; they

even stole the lead from the roofs of churches. Though their entry into

Constantinople itself was strictly controlled, only small parties of sightseers

being admitted through the gates, it was impossible to police the whole

neighbourhood.

Walter Sans-Avoir and his men were already at

Constantinople, and various bands of Italian pilgrims arrived there about the

same time. They joined up with Peter’s expedition; and on 6 August the whole of

his forces were conveyed across the Bosphorus. From the Asiatic shore they

marched in an unruly manner, pillaging houses and churches, along the coast of

the Sea of Marmora to Nicomedia, which lay deserted since its sack by the Turks

fifteen years before. There a quarrel broke out between the Germans and the

Italians on the one side and the French on the other. The former broke away

from Peter’s command and elected as their leader an Italian lord called

Rainald. At Nicomedia the two parts of the army turned westward along the south

coast of the Gulf of Nicomedia to a fortified camp called Cibotos by the Greeks

and Civetot by the Crusaders, which Alexius had prepared for the use of his own

English mercenaries in the neighbourhood of Helenopolis. It was a convenient

camping-ground, as the district was fertile and further supplies could easily

be brought by sea from Constantinople.

Raids of the

Crusaders

Alexius had urged Peter to await the coming of

the main Crusading armies before attempting any attack on the infidel; and

Peter was impressed by his advice. But Peter’s authority was waning. Both the

Germans and Italians, under Rainald, and his own Frenchmen, over whom Geoffrey

Burel seems to have held the chief influence, instead of quietly recuperating

their strength, vied with each other in raiding the countryside. First they

pillaged the immediate neighbourhood; then they cautiously advanced into

territory held by the Turks, making forays and robbing the villagers, who were

all Christian Greeks. In the middle of September several thousand of the

Frenchmen ventured as far as the gates of Nicaea, the capital of the Seldjuk

Sultan, Kilij Arslan ibn-Suleiman. They sacked the villages in the suburbs,

rounding up the flocks and herds that they found and torturing and massacring

the Christian inhabitants with horrifying savagery. It was said that they

roasted babies on spits. A Turkish detachment sent out from the city was driven

off after a fierce combat. They then returned to Civetot, where they sold their

booty to their comrades and to the Greek sailors who were about the camp.

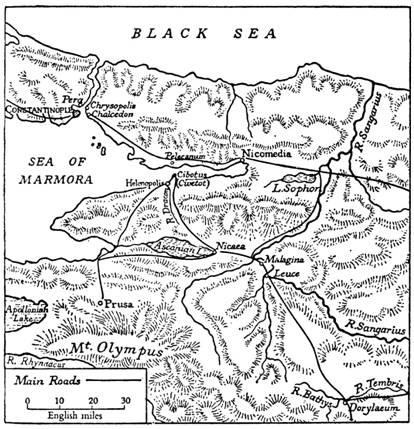

Environs of

Constantinople and Nicaea at the time of the First Crusade

This profitable French raid roused the jealousy

of the Germans. Towards the end of September Rainald set out with a German expedition

of some six thousand men, including priests and even bishops. They marched

beyond Nicaea, pillaging as they went, but, kinder than the Frenchmen, sparing

the Christians, till they came to a castle called Xerigordon. This they managed

to capture; and, finding it well stocked with provisions of every sort, they

planned to make it a centre from which they could raid the countryside. On

hearing of the Crusaders’ exploit, the Sultan sent a high military commander

with a large force to recapture the castle. Xerigordon was set on a hill, and

its water supply came from a well just outside the walls and a spring in the

valley below. The Turkish army, arriving before the castle on St Michael’s Day,

29 September, defeated an ambush laid by Rainald and, taking possession of the

spring and the well, kept the Germans closely invested within the castle. Soon

the besieged grew desperate from thirst. They tried to suck moisture from the

earth; they cut the veins of their horses and donkeys to drink their blood;

they even drank each other’s urine. Their priests tried vainly to comfort and

encourage them. After eight days of agony Rainald decided to surrender. He

opened the gates to the enemy on receiving a promise that his life would be

spared if he renounced Christianity. Everyone that remained true to the faith

was slaughtered. Rainald and those that apostasized with him were sent into captivity,

to Antioch and to Aleppo and far into Khorassan.

The Disaster at

Civetot

News of the capture of Xerigordon by the

Germans had reached the camp at Civetot early in October. It was followed by a

rumour, spread by two Turkish spies, that they had taken Nicaea itself and were

dividing up the booty for their benefit. As the Turks expected, this caused

tumultuous excitement in the camp. The soldiers clamoured to be allowed to

hasten to Nicaea, along roads that the Sultan had carefully ambushed. Their leaders

had difficulty in restraining them, till suddenly the truth was discovered

about the fate of Rainald’s expedition. The excitement was changed to panic;

and the chiefs of the army met to discuss what next to do. Peter had gone to

Constantinople. His authority over the army had vanished. He hoped to revive it

by obtaining some important material aid from the Emperor. There was a movement

in the army to go out to avenge Xerigordon. But Walter Sans-Avoir persuaded his

colleagues to await Peter’s return, which was due in eight days’ time. Peter,

however, did not return; and meanwhile it was reported that the Turks were

approaching in force towards Civetot. The army council met again. The more

responsible leaders, Walter Sans-Avoir, Rainald of Breis, Walter of Breteuil

and Fulk of Orleans, and the Germans, Hugh of Tubingen and Walter of Teck,

still urged that nothing should be done till Peter arrived. But Geoffrey Burel,

with the public opinion of the army behind him, insisted that it would be

cowardly and foolish not to advance against the enemy. He had his way. On 21

October, at dawn, the whole army of the Crusaders, numbering over 20,000 men,

marched out from Civetot, leaving behind them only old men, women and children

and the sick.