A History of the Crusades-Vol 1 (18 page)

At Cologne Emich decided that his work in the

Rhineland was completed. Early in June he set out with the bulk of his forces

up the Main towards Hungary. But a large party of his followers thought that

the Moselle valley also should be purged of Jews. They broke off from his army

at Mainz and on 1 June they arrived at Trier. Most of the Jewish community

there was safely given refuge by the archbishop in his palace; but as the

Crusaders approached some Jews in panic began to fight among themselves, while

others threw themselves into the Moselle and were drowned. Their persecutors

then moved on to Metz, where twenty-two Jews perished. About the middle of June

they returned to Cologne, hoping to rejoin Emich; but, finding him gone, they

proceeded down the Rhine, spending from 24 to 27 June in massacring the Jews at

Neuss, Wevelinghofen, Eller and Xanten. Then they dispersed, some returning

home, others probably merging with the army of Godfrey of Bouillon.

News of Emich’s exploits reached the parties

that had already left Germany for the East. Volkmar and his followers arrived

at Prague at the end of May. On 30 June they began to massacre the Jews in the

city. The lay authorities were unable to curb them; and the vehement protests

of Bishop Cosmas were unheeded. From Prague Volkmar marched on into Hungary. At

Nitra, the first large town across the frontier, he probably attempted to take

similar action. But the Hungarians would not permit such behaviour. Finding the

Crusaders incorrigibly unruly they attacked and scattered them. Many were slain

and others captured. What happened to the survivors and to Volkmar himself is

unknown.

Gottschalk and his men, who had taken the road

through Bavaria, had paused at Ratisbon to massacre the Jews there. A few days

later they entered Hungary at Wiesselburg (Moson). King Coloman issued orders

that they should be given facilities for revictualling so long as they behaved

themselves. But from the outset they began to pillage the countryside, stealing

wine and com and sheep and oxen. The Hungarian peasants resisted these

exactions. There was fighting; several deaths occurred and a young Hungarian

boy was impaled by the Crusaders. Coloman brought up troops to control them and

surrounded them at the village of Stuhlweissenburg, a little further to the

east. The Crusaders were obliged to surrender all their arms and all the goods

that they had stolen. But trouble continued. Possibly they made some attempt to

resist; possibly Coloman had heard by now of the events at Nitra and would not

trust them even disarmed. As they lay at its mercy, the Hungarian army fell on

them. Gottschalk was the first to flee but was soon taken. All his men perished

in the massacre.

The End of Emich’s

Expedition

Some few weeks later Emich’s army approached

the Hungarian frontier. It was larger and more formidable than Gottschalk’s;

and King Coloman, after his recent experiences, was seriously alarmed. When

Emich sent to ask for permission to pass through his kingdom, Coloman refused

the request and sent troops to defend the bridge that led across a branch of

the Danube to Wiesselburg. But Emich was not to be deflected. For six weeks his

men fought the Hungarians in a series of petty skirmishes in front of the

bridge, while they set about building an alternative bridge for themselves. In

the meantime they pillaged the country on their side of the river. At last the

Crusaders were able to force their way across the bridge that they had built

and laid siege to the fortress of Wiesselburg itself. Their army was well

equipped and possessed siege-engines of such power that the fall of the town

seemed imminent. But, probably on the rumour that the king was coming up in

full strength, a sudden panic flung the Crusaders into disorder. The garrison

thereupon made a sortie and fell on the Crusaders’ camp. Emich was unable to

rally his men. After a short battle they were utterly routed. Most of them fell

on the field; but Emich himself and a few knights were able to escape owing to

the speed of their horses. Emich and his German companions eventually retired

to their homes. The French knights, Clarambald of Vendeuil, Thomas of La Fere

and William the Carpenter, joined other expeditions bound for Palestine.

The collapse of Emich’s Crusade, following so

soon after the collapse of Volkmar’s and Gottschalk’s Crusades, deeply

impressed western Christendom. To most good Christians it appeared as a

punishment meted out from on high to the murderers of the Jews. Others, who had

thought the whole Crusading movement to be foolish and wrong, saw in these

disasters God’s open disavowal of it all. Nothing had yet occurred to justify

the cry that echoed at Clermont, ‘Deus le volt’.

CHAPTER III

THE PRINCES AND

THE EMPEROR

‘

Will he make

many supplications unto thee? will he speak soft words unto thee? Will he make

a covenant with thee?’

JOB XLI, 3, 4

The western princes that had taken the Cross

were less impatient than Peter and his friends. They were ready to abide by the

Pope’s time-table. Their troops had to be gathered and equipped. Money had to

be raised for the purpose. They must arrange for the government of their lands

during an absence that might last for years. None of them was prepared to start

out before the end of August.

The first to leave his home was Hugh, Count of

Vermandois, known as Le Maisne, the younger, a surname translated most

inappropriately by the Latin chroniclers even in his own time as Magnus. He was

the younger son of King Henry I of France and of a princess of Scandinavian

origin, Anne of Kiev; a man of some forty years of age, of greater rank than

wealth, who had acquired his small county by marriage with its heiress, and had

never played a prominent part in French politics. He was proud of his lineage

but ineffectual in action. We cannot tell what were his motives in joining the

Crusade. No doubt he inherited the restlessness of his Scandinavian ancestors.

Perhaps he felt that in the East he could acquire the power and riches that

befitted his high birth. Probably his brother, King Philip, encouraged his

decision in order to ingratiate his family with the Papacy. Leaving his lands

in the care of his countess, he set out in late August for Italy, with a small

army composed of his vassals and some knights from his brother’s domains.

Before his departure he sent a special messenger ahead of him to

Constantinople, requesting the Emperor to arrange for his reception with the

honours due to a prince of royal blood. As he journeyed southward he was joined

by Drogo of Nesle and Clarambald of Vendeuil and William the Carpenter and

other French knights returning from Emich’s disastrous expedition.

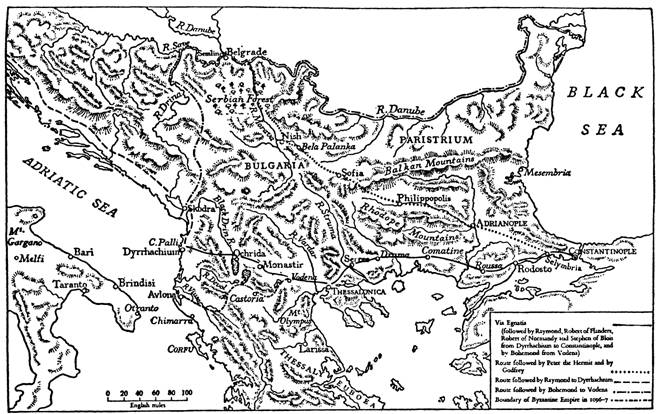

The Balkan

Peninsula at the time of the First Crusade

Hugh and his company passed by Rome and arrived

at Bari early in October. In southern Italy they found the Norman princes

themselves preparing for the Crusade; and Bohemond’s nephew William decided not

to wait for his relatives but to cross the sea with Hugh. From Bari Hugh sent

an embassy of twenty-four knights, led by William the Carpenter, across to

Dyrrhachium to inform the governor that he was about to arrive and to repeat

his demand for a suitable reception. The governor, John Comnenus, was thus able

to warn the Emperor of his approach and himself prepared to welcome him. But

Hugh’s actual arrival was not as dignified as he had hoped. A storm wrecked the

small flotilla that he had hired for the crossing. Some of his ships foundered

with all their passengers. Hugh himself was cast ashore on Cape Palli, a few

miles to the north of Dyrrhachium. John’s envoys found him there bewildered and

bedraggled, and escorted him to their master; who at once re-equipped him and

feasted him and showed him every attention, but kept him under strict

surveillance. Hugh was pleased with the flattering regard shown to him; but to

some of his followers it seemed that he was being kept a prisoner. He remained

at Dyrrhachium till a high official, the admiral Manuel Butumites, arrived from

the Emperor to escort him to Constantinople. His journey thither was achieved

in comfort, though he was obliged to take a roundabout route through

Philippopolis, as the Emperor did not wish to let him make contact with the

Italian pilgrims that were crowding along the Via Egnatia. At Constantinople

Alexius greeted him warmly and showered presents on him but continued to

restrict his liberty.

Godfrey of

Lorraine

Hugh’s arrival forced Alexius to declare his

policy towards the western princes. The information that he had acquired and

his memory of the career of Roussel of Bailleul convinced him that, whatever

might be the official reasons for the Crusade, the real object of the Franks

was to secure for themselves principalities in the East. He did not object to

this. So long as the Empire recovered all the lands that it had held before the

Turkish invasions, there was much to be said in favour of the creation of

Christian buffer-states on its perimeter. That small states could be

independent was unthought-of at the time. But Alexius wished to be sure that he

would be clearly regarded as overlord of any that might be erected. Knowing

that in the West allegiance was established by a solemn oath, he decided to

demand such an oath from all the western leaders to cover their future

conquests. To win their compliance he was ready to pour gifts and subsidies on

them, while he would emphasize his own wealth and glory, that they might not

feel their dignity lowered in becoming his men. Hugh, dazzled by the

magnificence and the generosity of the Emperor, fell in willingly with his

plans. But the next to arrive from the West was not so easily persuaded.

Godfrey of Bouillon, Duke of Lower Lorraine,

appears in later legend as the perfect Christian knight, the peerless hero of

the whole Crusading epic. A scrupulous study of history must modify the

verdict. He was born about the year 1060, the second son of Count Eustace II of

Boulogne and of Ida, daughter of Godfrey II, Duke of Lower Lorraine, who was

descended in the female line from Charlemagne. He had been designated as the

heir to the possessions of his mother’s family; but on her father’s death the

emperor Henry IV confiscated the duchy, leaving Godfrey only the county of

Antwerp and the lordship of Bouillon in the Ardennes. Godfrey, however, served

Henry so loyally in his German and Italian campaigns that in 1082 he was

invested with the duchy, but as an office, not as a hereditary fief. Lorraine

was impregnated with Cluniac influences; and, though Godfrey remained loyal to

the emperor, it is possible that Cluniac teaching, with its strong papal

sympathies, began to trouble his conscience. His administration of Lorraine was

not very efficient. There seems to have been some doubt whether Henry would

continue to employ him. It was therefore partly from despondency about his

future in Lorraine, partly from uneasiness over his religious loyalties, and

partly from genuine enthusiasm that he answered the call to the Crusade. He

made his preparations very thoroughly. After raising money by blackmailing the

Jews, he sold his estates of Rosay and Stenay on the Meuse, and pledged his

castle of Bouillon to the Bishop of Liege, and was thus able to equip an army

of considerable size. The number of his troops and his former high office gave

Godfrey a prestige that was enhanced by his pleasant manners and his handsome

appearance. For he was tall, well-built and fair, with a yellow beard and hair,

the ideal picture of a northern knight. But he was indifferent as a soldier,

and as a personality he was overshadowed by his younger brother, Baldwin.

Godfrey in

Hungary

Godfrey’s two brothers had also taken the

Cross. The elder, Eustace III, Count of Boulogne, was an unenthusiastic

Crusader, always eager to return to his rich lands that lay on both sides of

the English Channel. His contribution of soldiers was far smaller than Godfrey’s,

whom he was therefore content to regard as leader. He probably travelled out

separately, going through Italy. The younger brother, Baldwin, who accompanied

Godfrey, was of a different type. He had been destined for the Church and so

had not been allotted any of the family estates. But, though his training at

the great school at Reims left him with a lasting taste for culture, his

temperament was not that of a churchman. He returned to lay life, and

apparently took service under his brother Godfrey in Lorraine. The brothers

formed a striking contrast. Baldwin was even taller than Godfrey. His hair was

as dark as the other’s was fair; but his skin was very white. While Godfrey was

gracious in manner, Baldwin was haughty and cold. Godfrey’s tastes were simple,

but Baldwin, though he could endure great hardships, loved pomp and luxury.

Godfrey’s private life was chaste, Baldwin’s given over to venery. Baldwin

welcomed the Crusade with delight. His home-land offered him no future; but in

the East he might find himself a kingdom. When he set out he took with him his

Norman wife, Godvere of Tosni, and their little children. He did not intend to

return.

Godfrey and his brothers were joined by many

leading knights from Walloon and Lotharingian territory; their cousin, Baldwin

of Rethel, lord of Le Bourg, Baldwin II, Count of Hainault, Rainald, Count of

Toul, Warner of Gray, Dudo of Konz-Saarburg, Baldwin of Stavelot, Peter of

Stenay and the brothers Henry and Geoffrey of Esch.

Perhaps because he felt some embarrassment as

an imperialist in his relations with the Papacy, Godfrey decided not to travel

through Italy by the route that the other crusading leaders were planning to

take. Instead, he would go through Hungary, following not only the popular

Crusades but also, according to the legend that was now spreading through the

West, his ancestor Charlemagne himself on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He left

Lorraine at the end of August, and after a few weeks’ marching up the Rhine and

down the Danube he arrived at the beginning of October at the Hungarian

frontier on the river Leitha. From there he sent an embassy, headed by Geoffrey

of Esch, who had previous experience of the Hungarian court, to King Coloman to

ask for permission to cross his territory.

Coloman had recently suffered too severely at

the hands of Crusaders to welcome a new invasion. He kept the embassy for eight

days, then announced that he would meet Godfrey at Oedenburg for an interview.

Godfrey came with a few of his knights and was invited to spend some days at

the Hungarian court. The impression that Coloman received from this visit

decided him to allow the passage of Godfrey’s army through Hungary, provided

that Baldwin, whom he guessed to be its most dangerous member, was left with

him as a hostage, together with his wife and children. When Godfrey returned to

his army, Baldwin at first refused to give himself up; but he later consented;

and Godfrey and his troops entered the kingdom at Oedenburg. Coloman promised

to provide them with provisions at reasonable prices; while Godfrey sent

heralds round his army to announce that any act of violence would be punished

by death. After these precautions had been taken the Crusaders marched

peaceably through Hungary, the king and his army keeping close watch on them

all the way. After spending three days revictualling at Mangjeloz, close to the

Byzantine frontier, Godfrey reached Semlin towards the end of November and took

his troops in an orderly manner across the Save to Belgrade. As soon as they

were all across, the hostages were returned to him.

Godfrey s

Arrival at Constantinople

The imperial authorities, probably forewarned

by the Hungarians, were ready to welcome him. Belgrade itself had lain deserted

since its pillage by Peter, five months before. But a frontier guard hurried to

Nish, where the governor Nicetas was residing and where an escort for Godfrey

was waiting. The escort set out at once and met him in the Serbian forest,

half-way between Nish and Belgrade. Arrangements for provisioning the army had

already been made; and it moved on without trouble through the Balkan peninsula.

At Philippopolis news reached it of the arrival of Hugh of Vermandois at

Constantinople and of the wonderful gifts that he and his comrades had

received. Baldwin of Hainault and Henry of Esch were so deeply impressed that

they decided to hasten on ahead of the army to the capital in order to secure

their share in the gifts before the others came. But rumour also reported, not entirely

without foundation, that Hugh was being kept a prisoner, Godfrey was somewhat

disquieted.

On about 12 December Godfrey’s army halted at

Selymbria, on the Sea of Marmora. There its discipline, which had hitherto been

excellent, suddenly broke down; and for eight days it ravaged the countryside.

The reason for this disorder is unknown; but Godfrey sought to excuse it as

reprisals for Hugh’s imprisonment. The Emperor Alexius promptly sent two

Frenchmen in his service, Radulph Peeldelau and Roger, son of Dagobert, to

remonstrate with Godfrey and to persuade him to continue his march in peace.

They succeeded; and on 23 December Godfrey’s army arrived at Constantinople and

encamped, at the request of the Emperor, outside the city along the upper

waters of the Golden Horn.

Godfrey’s arrival with a large and

well-equipped army presented a difficult problem to the imperial government. In

pursuit of his policy, Alexius wished to make sure of Godfrey’s allegiance and

then to send him on as soon as possible out of the dangerous neighbourhood of

the capital. It is doubtful whether he really suspected, as his daughter Anna

suggests, that Godfrey had designs on Constantinople. But the suburbs of the

city had already suffered severely from the ravages of Peter the Hermit’s

followers. It was dangerous to expose them to the attentions of an army that

had proved itself equally lawless and was far better armed. But he had first to

secure Godfrey’s oath of homage. Accordingly, as soon as Godfrey was settled in

his camp, Hugh of Vermandois was sent to visit him, to persuade him to come to

see the Emperor. Hugh, so far from resenting his treatment at the Emperor’s

hands, willingly undertook the mission.

Godfrey refused the Emperor’s invitation. He

felt out of his depth. Hugh’s attitude puzzled him. His troops had already made

contact with the remnants of Peter’s forces, most of whom justified their recent

disaster by attributing it to imperial treachery; and he was affected by their

propaganda. As Duke of Lower Lorraine he had taken a personal oath of

allegiance to the emperor Henry IV, and may have thought that this precluded an

oath to the rival eastern Emperor. Moreover, he did not wish to take any

important step till he could consult the other Crusading leaders whom he knew

to be soon arriving. Hugh returned to the palace without an answer for Alexius.

Alexius was angry, and unwisely thought to

bring Godfrey to reason by shutting off the supplies that he had promised to

provide for his troops. While Godfrey hesitated, Baldwin at once began to raid

the suburbs, till Alexius promised to lift the blockade. At the same time

Godfrey agreed to move his camp down the Golden Horn to Pera, where it would be

better sheltered from the winter winds, and where the imperial police could

watch it more closely. For some time neither side took further action. The

Emperor supplied the western troops with sufficient provisions; and Godfrey for

his part saw that discipline was maintained. At the end of January Alexius

again invited Godfrey to visit him; but Godfrey was still unwilling to commit

himself till other Crusading leaders should join him. He sent his cousin, Baldwin

of Le Bourg, Conon of Montaigu and Geoffrey of Esch to the palace to hear the

Emperor’s proposals, but on their return gave no answer. Alexius was unwilling

to provoke Godfrey lest he should again ravage the suburbs. After ensuring that

the Lorrainers had no communication with the outside world, he waited till

Godfrey should grow impatient and come to terms.

The Battle in

Holy Week

At the end of March Alexius learnt that other

Crusading armies would soon arrive at Constantinople. He felt obliged to bring

matters to a head, and began to reduce the supplies sent to the Crusaders’

camp. First he withheld fodder for their horses, then, as Holy Week approached,

their fish and finally bread. The Crusaders responded by making daily raids on

the neighbouring villages and eventually came into conflict with the Petcheneg

troops that acted as police in the districts. In revenge Baldwin set an ambush

for the police. Sixty were captured and many of them were put to death.

Encouraged by the small success and feeling that he was now committed to fight,

Godfrey decided to move his camp and to attack the city itself. After carefully

plundering and burning the houses in Pera in which his men had been lodged, he

led them across a bridge over the head waters of the Golden Horn, drew them up

outside the city walls and began to attack the gate that led to the palace

quarter of Blachernae. It is doubtful whether he meant to do more than put

pressure on the Emperor; but the Greeks suspected that he aimed at seizing the

Empire.

It was the Thursday in Holy Week, 2 April; and

Constantinople was quite unprepared for such an onslaught. There were signs of

a panic in the city, which was only stilled by the presence and the cool

behaviour of the Emperor. He was genuinely shocked by the necessity for

fighting on so holy a day. He ordered his troops to make a demonstration

outside the gates without coming to blows with the enemy, while his archers on

the walls were told to fire over their heads. The Crusaders did not press their

attack and soon retired, having slain only seven of the Byzantines. Next day

Hugh of Vermandois again went out to remonstrate with Godfrey, who retorted by

taunting him with slavishness for having so readily accepted vassaldom. When

envoys were sent by Alexius to the camp later in the day to suggest that

Godfrey’s troops should cross over to Asia even before Godfrey took the oath,

the Crusaders advanced to attack them without waiting to hear what they might

say. Thereupon Alexius decided to finish the affair, and flung in more of his

men to meet the attack. The Crusaders were no match for the seasoned imperial

soldiers. After a brief contest they turned and fled. His defeat brought

Godfrey at last to recognize his weakness. He consented both to take the oath

of allegiance and to have his army transported across the Bosphorus.

The ceremony of the oath-taking was held

probably two days later, on Easter Sunday. Godfrey, Baldwin and their leading

lords swore to acknowledge the Emperor as overlord of any conquests that they might

make and to hand over to the Emperor’s officials any reconquered land that had

previously belonged to the Emperor. They then received huge gifts of money and

were entertained by the Emperor at a banquet. As soon as the ceremonies were

over, Godfrey and his troops were shipped across to Chalcedon and marched on to

an encampment at Pelecanum, on the road to Nicomedia.

The Ceremony of

Homage

Alexius had very little time to spare. Already

a miscellaneous army, probably composed of various vassals of Godfrey who had

preferred to travel through Italy and were probably led by the Count of Toul,

had arrived at the outer suburbs of the city and were waiting on the shores of

the Marmora, near Sosthenium. They showed the same truculence as Godfrey, and

were anxious to wait for Bohemond and the Normans, whom they knew to be close

behind; while the Emperor was determined to prevent their junction with

Godfrey. It was only after some fighting that he could keep control over their

movements; and as soon as Godfrey was safely across the Bosphorus he conveyed

them by sea to the capital, where they joined other small groups of Crusaders

that had straggled across the Balkans. All the Emperor’s tact and many gifts

were needed to persuade their leaders to take the oath of allegiance. When at

last they consented, Alexius enhanced the solemnity of the occasion by bringing

over Godfrey and Baldwin to witness the ceremony. The western lords were

grudging and unruly. One of them sat himself down on the Emperor’s throne;

whereupon Baldwin sharply reproved him, reminding him that he had just become

the Emperor’s vassal and telling him to observe the customs of the country. The

westerner angrily muttered that it was boorish of the Emperor to sit when so

many valiant captains were standing. Alexius, who overheard the remark and had

it translated for him, asked to speak with the knight; and when the latter

began to boast of his unbeaten prowess in single combat, Alexius gently advised

him to try other tactics when fighting the Turks.

The incident typified the relations between the

Emperor and the Franks. The crude knights from the West were inevitably

impressed by the splendour of the palace and by its smooth, careful ceremonial

and the quiet, polished manners of the courtiers. But they resented it all.

Their wounded pride made them obstreperous and rude, like naughty children.

When their oaths were taken the knights and

their men were transported across the straits to join Godfrey’s army on the

coast of Asia. The Emperor had acted just in time. On 9 April Bohemond of

Taranto arrived at Constantinople.