A History of the Crusades-Vol 2 (14 page)

1113: Baldwin s

Marriage with Adelaide

Baldwin himself made one serious lapse with

regard to his marriage. He had never much cared for his Armenian bride since

the day that her father, terrified of his ruthless son-in-law, had decamped

with her promised dowry. Baldwin was fond of amorous adventures; but he was

discreet and the presence of a queen at the court prevented him from indulging

in his tastes. The Queen also had a reputation for gaiety and had even, it was

said, bestowed her favours upon Moslem pirates when she was voyaging down from

Antioch to take over her throne. There were no children to bind them together.

After a few years, when there was no longer the smallest political advantage to

the marriage, Baldwin dismissed her from the Court on the grounds of adultery

and obliged her to enter into the convent of St Anne in Jerusalem, which, to salve

his conscience, he richly endowed. But the Queen had no vocation for the

monastic life. She soon demanded and received permission to retire to

Constantinople, where her parents had been living since their ejection from

Marash by the Franks. There she abandoned her monastic robe and settled down to

taste all the pleasures that the great city provided. Meanwhile Baldwin

rejoiced to find himself able to lead a bachelor life once more. But he still

needed money; and in the winter of 1112 he learnt that the most eligible widow

in Europe was seeking a husband. Adelaide of Salona, Countess-Dowager of

Sicily, had just retired from the regency of her county on the coming-of-age of

her young son, Roger II. She was immensely rich; and a royal title attracted

her. To Baldwin she was desirable not only for her dowry but also for her

influence over the Normans of Sicily; whose alliance would help to supply him

with sea-power and would act as a counter-weight against the Normans of

Antioch. He sent to ask for her hand. The Countess accepted on her own terms.

Baldwin was childless. The children of his first wife had died in Anatolia

during the First Crusade; and his Armenian Queen had borne him none. Adelaide

insisted that if no baby was born of her marriage to Baldwin — and the ages of

the bride and bridegroom gave little promise of a baby — the crown of Jerusalem

was to pass to her son, Count Roger.

The contract was made; and in the summer of

1113 the Countess set out from Sicily in such splendour as had not been seen on

the Mediterranean since Cleopatra sailed for the Cydnus to meet Mark Antony.

She lay on a carpet of golden thread in her galley, whose prow was plated with

silver and with gold. Two other triremes accompanied her, their prows equally

ornate, bearing her military escort, prominent amongst whom were the Arab

soldiers of her son’s own bodyguard, their dark faces shining against the

spotless white of their robes. Seven other ships followed in her wake, their

holds laden with all her personal treasure. She landed at Acre in August. There

King Baldwin met her, with all the pomp that his kingdom could provide. He and

all his Court were clad in costly silks; and their horses and mules were hung

with purple and gold. Rich carpets were laid in the streets, and from the

windows and balconies fluttered purple banners. The towns and villages along

the road to Jerusalem bore like finery. All the country rejoiced, but not so

much at the coming of its new, ageing mistress as at the wealth that she

brought in her train.

Despite its gorgeous beginning, the marriage

was not a success. Baldwin at once took over the Queen’s dowry, which he used

to pay off the overdue wages of his soldiers and to spend on works of

fortification; and the money coming into circulation enriched the commerce of

the country. But the effect soon wore off; and the disadvantages of the

marriage became apparent. Pious folk remembered that Baldwin’s previous wife

had never been legally divorced. They were shocked that the Patriarch Arnulf

had so willingly performed what was in fact a bigamous marriage ceremony; and

Arnulf’s many enemies were quick to make use of this irregularity. Their attack

might have been less effective had not all Baldwin’s subjects been angered when

they discovered that he proposed to dispose of the succession to the kingdom

without consulting his council. Complaints against Arnulf poured into Rome. A

year after the royal marriage a papal legate, Berengar, Bishop of Orange,

arrived at Jerusalem. When he found that added to the charges of simony against

Arnulf there was the certainty that he had condoned and blessed an adulterous

connection, he summoned the bishops and abbots of the Patriarchate to a synod

and declared Arnulf deposed. But Arnulf could not be disposed of so easily. He

saw to it that no successor was appointed and himself went off in the winter of

1115 to Rome. There he used all his persuasive charm on the Pope and the

Cardinals, whose sympathies were strengthened by the well-chosen gifts that he

made to them. Paschal fell under his influence and repudiated his legate’s

decision. Arnulf made one concession; he promised to order the King to dismiss

his Sicilian Queen. On those terms the Pope not only declared that Arnulf’s

deposition was void but himself presented him with the pallium, thus placing

his position beyond all question. In the summer of 1116 Arnulf returned

triumphant to Jerusalem.

1118: The Death

of Princes

The concession was willingly made; for Arnulf

knew that Baldwin, now that Adelaide’s dowry was spent, was half-regretful of

his marriage. Nor did Adelaide, used to the luxuries of the palace at Palermo,

find the discomforts of Solomon’s Temple at Jerusalem much to her liking. But

Baldwin hesitated; he was unwilling to lose the advantages of the Sicilian

alliance. He resisted Arnulf’s demands; till in March 1117 he fell seriously

ill. Face to face with death he listened to his confessors, who told him that

he was dying in a state of sin. He must dismiss Adelaide and call his former

wife to his side. He could not carry out all their wishes; for the ex-Queen was

not prepared to leave Constantinople, whose gallant pleasures she so richly

enjoyed. But when he recovered, he announced the annulment of his marriage to

Adelaide. Adelaide herself, shorn of her wealth and almost unescorted, sailed

angrily back to Sicily. It was an insult that the Sicilian Court never forgave.

It was long before the kingdom of Jerusalem was to receive any aid or sympathy

from Sicily.

On 16 June 1117 there was an eclipse of the

moon and another on 11 December, and five nights later the rare phenomenon of

the aurora borealis flickered through the Palestinian sky. It was a terrible

portent, foretelling the death of princes. Nor did it lie. On 21 January 1118

Pope Paschal died at Rome. On 16 April the ex-Queen Adelaide ended her

humiliated existence in Sicily. Her false friend the Patriarch Arnulf survived

her for only twelve days. 5 April saw the death of the Sultan Mohammed in Iran.

On 6 August the Caliph Mustazhir died at Baghdad. On 15 August, after a

long and painful illness, the greatest of the eastern potentates, the Emperor

Alexius, died at Constantinople.

In the early spring King Baldwin

returned fever-stricken from Egypt. His worn, overstrained body had no

resistance left in it. His soldiers carried him back, a dying man, to the

little frontier-fort of el-Arish. There, just beyond the borders of the kingdom

which owed to him its existence, he died on 2 April, in the arms of the Bishop

of Ramleh. His corpse was brought to Jerusalem, and on Palm Sunday, 7 April, it

was laid to rest in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, by the side of his

brother Godfrey.

Lamentations accompanied the funeral

procession, from Franks and native Christians alike; and even the visiting

Saracens were moved. He had been a great King, harsh and unscrupulous, not

loved but deeply respected for his energy, his foresight and the order and

justice of his rule. He had inherited a tenuous, uncertain realm, but by his

martial vigour, his diplomatic subtlety and his wise tolerance he had given it

a solid place amongst the kingdoms of the East.

CHAPTER VI

EQUILIBRIUM IN

THE NORTH

‘

They shall

fight every one against his brother

,

and every one against his

neighbour.’

ISAIAH XIX, 2

Some years before he died, King Baldwin I had established

himself as the unquestioned leader of the Franks in the East. It had not been

an easy achievement; and Baldwin succeeded in it by his subtle use of

circumstances.

The capture of Baldwin of Le Bourg and Joscelin

of Courtenay at Harran and the departure of Bohemond to the West had left

Tancred without a rival among the Franks of northern Syria; and dissensions

amongst the Moslems had enabled him to take full advantage of his

opportunities. The Seldjuk empire was crumbling to pieces, less from pressure

from outside than from the quarrels of its princes. The victory at Harran had

brought Jekermish, the atabeg of Mosul, to the fore amongst the Turkish

magnates in northern Syria and the Jezireh. The disastrous failure of his

attempt to pursue the offensive against the Franks had not weakened his

position among his fellow-Moslems. His former ally and rival, Soqman the

Ortoqid of Mardin, had died early in 1105, on his way to help beleaguered

Tripoli; and Soqman’s brother Ilghazi and son Ibrahim disputed the inheritance.

Ridwan of Aleppo had hoped that the victory of Ilghazi, who had formerly served

under him, would give him influence in the Jezireh; but Ilghazi forgot past

loyalties; and Ridwan himself was too deeply involved against the Franks of

Antioch to assert his old overlordship. The great Danishmend emir, Malik Ghazi

Gumushtekin, died in 1106, leaving his dominions divided. Sivas and his

Anatolian lands went to Ghazi, his elder son, and Melitene and his Syrian lands

to the younger, Sangur. Sangur’s youth and inexperience tempted Kilij Arslan,

who had recently made peace with Byzantium, to turn eastward and to attack

Melitene, which he captured in the autumn of 1106. He then attempted to have

his self-assumed title of Sultan recognized throughout the Turkish world and

was ready to make friends with anyone that would humour him in this.

Jekermish did not enjoy his pre-eminence for

long. He was inevitably involved in the quarrels of the Seldjuk Sultanate of

the East. When the Sultan Barkiyarok in 1104 was obliged to share his dominion

with his brother Mohammed, Mosul was allotted to the latter’s sphere. Jekermish

tried to achieve independence by declaring that his allegiance was to

Barkiyarok alone, and defied Mohammed’s troops; but in January 1105, Barkiyarok

died and his inheritance passed in its entirety to Mohammed. Jekermish was

deprived of his excuse and hastened to submit to Mohammed; who for the moment

professed friendship and retired eastward without venturing to make a

triumphant entry into Mosul.

Probably at Mohammed’s request,

Jekermish then set about the organization of a new campaign against the Franks.

He formed a coalition with Ridwan of Aleppo and Ridwan’s lieutenant, the

aspahbad

Sabawa, Ilghazi the Ortoqid, and his own son-in-law, Albu ibn Arslantash of

Sinjar. The allies suggested to Ridwan and Albu that it would be more politic

and profitable to please the Sultan by an attack on Jekermish. They marched

together on his second city, Nisibin; but there his agents succeeded in

embroiling Ridwan with Ilghazi, whom Ridwan kidnapped at a banquet before the

walls of Nisibin and loaded with chains. The Ortoqid troops then attacked

Ridwan and forced him to retire to Aleppo. Jekermish was thus saved, and then

himself attacked Edessa; but after successfully defeating a sortie of Richard

of the Principate’s troops, he returned home, to face fresh trouble.

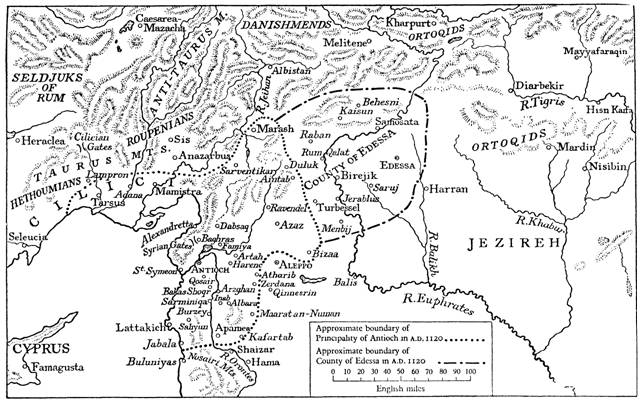

Map 1. Northern

Syria in the twelfth century.

Meanwhile Kilij Arslan, who had just taken over

Melitene, in his turn made an attempt against Edessa; but, finding it too

strongly defended, he moved on to Harran, which was surrendered to him by

Jekermish’s garrison. It was clear that the Seldjuks of Rum sought to expand

their power in the Moslem world at the expense of their Persian cousins.

The Sultan Mohammed had never forgiven

Jekermish for his independent airs, and he suspected some collusion between him

and Kilij Arslan. In the winter of 1106 he officially deprived him of Mosul and

gave it, with the lordship of the Jezireh and Diarbekr, to a Turkish adventurer

called Jawali Saqawa. Jawali led an army against Jekermish, who advanced to

meet him but was defeated just outside the city and was himself captured. The

inhabitants of Mosul, where Jekermish had been a popular ruler, at once

proclaimed his young son Zenki as atabeg; while friends outside the city

summoned the help of Kilij Arslan. Jawali thought it prudent to retire,

especially as Jekermish, whom he had hoped to use as a bargaining counter,

suddenly died on his hands. Mosul opened its gates to Kilij Arslan, who

promised to respect its liberties.