A History of the Crusades-Vol 2 (19 page)

CHAPTER I

KING BALDWIN II

‘

There shall

not fail thee a man upon the throne of Israel.’

I KINGS IX, 5

Baldwin I had neglected his final duty as King;

he made no arrangement for the succession to the throne. The council of the

kingdom hastily met. To some of the nobles it seemed unthinkable that the crown

should pass from the house of Boulogne. Baldwin I had succeeded his brother

Godfrey; and there was still a third brother, the eldest, Eustace, Count of

Boulogne. Messengers were hastily dispatched over the sea to inform the Count

of his brother’s death and to beg him to take up the heritage. Eustace had no

wish to leave his pleasant country for the hazards of the East; but they told

him that it was his duty. He set out towards Jerusalem. But when he reached

Apulia he met other messengers, with the news that it was too late. The

succession had passed elsewhere. He refused the suggestion that he should

continue on his way and fight for his rights. Not unwillingly, he retraced his

steps to Boulogne.

Indeed, few of the council had favoured his

succession. He was far away; it would mean an interregnum of many months. The

most influential member of the council was the Prince of Galilee, Joscelin of

Courtenay; and he demanded that the throne be given to Baldwin of Le Bourg,

Count of Edessa. He himself had no cause to love Baldwin, as he carefully

reminded the council; for Baldwin had falsely accused him of treachery and had

exiled him from his lands in the north. But Baldwin was a man of proved ability

and courage; he was the late King’s cousin; and he was the sole survivor of the

great knights of the First Crusade. Moreover, Joscelin calculated that if

Baldwin left Edessa for Jerusalem the least that he could do to reward the

cousin who had requited his unkindness so generously was to entrust him with

Edessa. The Patriarch Arnulf supported Joscelin and together they persuaded the

council. As if to clinch their argument, on the very day of the King’s funeral,

Baldwin of Le Bourg appeared unexpectedly in Jerusalem. He had heard, maybe, of

the King’s illness of the previous year and thought it therefore opportune to

pay an Easter pilgrimage to the Holy Places. He was received with gladness and

unanimously elected king by the Council. On Easter Sunday, 14 April 1118, the

Patriarch Arnulf placed the crown on his head.

Baldwin II differed greatly as a man from his

predecessor. Though handsome enough, with a long fair beard, he lacked the

tremendous presence of Baldwin I. He was more approachable, genial and fond of

a simple joke, but at the same time subtle and cunning, less open, less rash,

more self-controlled. He was capable of large gestures but in general somewhat

mean and ungenerous. Despite a high-handed attitude to ecclesiastical affairs,

he was genuinely pious; his knees were callous from constant prayer. Unlike

Baldwin I’s, his private life was irreproachable. With his wife, the Armenian

Morphia, he presented a spectacle, rare in the Frankish East, of perfect

conjugal bliss.

Joscelin was duly rewarded with the county of

Edessa, to hold it as vassal to King Baldwin, just as Baldwin himself had held

it under Baldwin I. The new King was also recognized as overlord by Roger of

Antioch, his brother-in-law, and by Pons of Tripoli. The Frankish East was to

remain united under the crown of Jerusalem. A fortnight after Baldwin’s

coronation the Patriarch Arnulf died. He had been a loyal and efficient servant

of the state; but, in spite of his prowess as a preacher, he had been involved

in too many scandals to be respected as an ecclesiastic. It is doubtful if

Baldwin much regretted his death. In his place he secured the election of a

Picard priest, Gormond of Picquigny, of whose previous history nothing is

known. It was a happy choice; for Gormond combined Arnulf’s practical qualities

with a saintly nature and was universally revered. This appointment, following

on the recent death of Pope Paschal, restored good relations between Jerusalem

and Rome.

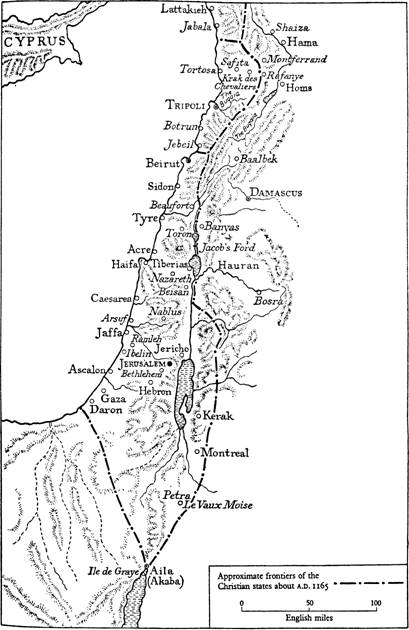

Map 2. Southern

Syria in the twelfth century.

King Baldwin had barely established himself on

the throne before he heard the ominous news of an alliance between Egypt and

Damascus. The Fatimid vizier, al-Afdal, was anxious to punish Baldwin I’s

insolent invasion of Egypt; while Toghtekin of Damascus was alarmed by the

growing power of the Franks. Baldwin hastily sent him an embassy; but confident

of Egyptian help Toghtekin demanded the cession of all Frankish lands beyond

Jordan. In the course of the summer a great Egyptian army assembled on the

frontier and took up its position outside Ashdod; and Toghtekin was invited to

take command of it. Baldwin summoned the militia of Antioch and Tripoli to

reinforce the troops of Jerusalem, and marched down to meet them. For three

months the armies faced each other, neither side daring to move; for everyone,

in Fulcher of Chartres’s words, liked better to live than to die. At last the

soldiers on either side dispersed to their homes.

1119: Raids in

Transjordan

Meanwhile,

Joscelin’s departure for Edessa was delayed. He was more urgently needed in

Galilee than in the northern county, where, it seems, Queen Morphia remained,

and where Waleran, Lord of Birejik, carried on the government. As Prince of

Galilee it was for Joscelin to defend the land against attacks from Damascus.

In the autumn Baldwin joined him in a raid on Deraa in the Hauran, the granary

of Damascus. Toghtekin’s son Buri went out to meet them and owing to his

rashness was severely defeated. After this check Toghtekin turned his attention

again to the north.

In the spring of 1119 Joscelin heard that a

rich Bedouin tribe was pasturing its flocks in Transjordan, by the Yarmuk. He

set out with two leading Galilean barons, the brothers Godfrey and William of

Bures, and about a hundred and twenty horsemen, to plunder it. The party

divided to encircle the tribesmen. But things went wrong. The Bedouin chief was

warned and Joscelin lost his way in the hills. Godfrey and William, riding up

to attack the camp, were ambushed. Godfrey was killed, and most of his

followers taken prisoner. Joscelin returned unhappily to Tiberias and sent to

tell King Baldwin; who came up in force and frightened the Bedouin into

returning the prisoners and paying an indemnity. They were then allowed to

spend the summer in peace.

When Baldwin was pausing at Tiberias on his

return from this short campaign, messengers came to him from Antioch, begging him

to hasten with his army northward, as fast as he could travel.

Ever since Roger of Antioch’s victory at

Tel-Danith, the unfortunate city of Aleppo had been powerless to prevent

Frankish aggression. It had reluctantly placed itself beneath the protection of

Ilghazi the Ortoqid; but Roger’s capture of Biza’a in 1119 left it surrounded

on three sides. The loss of Biza’a was more than Ilghazi could endure. Hitherto

neither he nor his constant ally, Toghtekin of Damascus, had been prepared to

risk their whole strength in a combat against the Franks; for they feared and

disliked still more the Seldjuk Sultans of the East. But the Sultan Mohammed

had died in April 1118; and his death had let loose the ambition of every

governor and princeling throughout his empire. His youthful son and successor,

Mahmud, tried pathetically to assert his authority, but eventually, in August

1119, he was obliged to hand over the supreme power to his uncle Sanjar, the

King of Khorassan, and spent the rest of his short life in the pleasures of the

chase. Sanjar, the last of his house to rule over the whole eastern Seldjuk

dominion, was vigorous enough; but his interests were in the East. He never

concerned himself with Syria. Nor were his cousins of the Sultanate of Rum,

distracted with quarrels amongst themselves and with the Danishmends and by

wars with Byzantium, better able to intervene in Syrian affairs.

Ilghazi,

the most tenacious of the local princes, at last had his opportunity. His wish

was not so much to destroy the Frankish states as to secure Aleppo for himself,

but the latter aim now involved the former.

During the spring of 1119 Ilghazi journeyed

round his dominions collecting his Turcoman troops and arranging for

contingents to come from the Kurds to the north and from the Arab tribes of the

Syrian desert. As a matter of form he applied for assistance from the Sultan

Mahmud, but received no answer. His ally, Toghtekin, agreed to come up from

Damascus; and the Munqidhites of Shaizar promised to make a diversion to the

south of Roger’s territory. At the end of May, the Ortoqid army, said to be

forty thousand strong, was on the march. Roger received the news calmly; but

the Patriarch Bernard urged him to appeal for help to King Baldwin and to Pons

of Tripoli. From Tiberias Baldwin sent to say that he would come as quickly as

possible and would bring the troops of Tripoli with him. In the meantime Roger

should wait on the defensive. Baldwin then collected the army of Jerusalem, and

fortified it with a portion of the True Cross, in the care of Evremar,

Archbishop of Caesarea.

1119: The Field

of Blood

While the Munqidhites made a raid on Apamea,

Ilghazi sent Turcoman detachments south-west, to effect a junction with them

and with the army coming up from Damascus. He himself with his main army raided

the territory of Edessa but made no attempt against its fortress-capital. In

mid-June he crossed the Euphrates at Balis and moved on to encamp himself at

Qinnasrin, some fifteen miles south of Aleppo, to await Toghtekin. Roger was

less patient. In spite of King Baldwin’s message, in spite of the solemn

warning of the Patriarch Bernard and in spite of all the previous experience of

the Frankish princes, he decided to meet the enemy at once. On 20 June he led

the whole army of Antioch, seven hundred horsemen and four thousand

infantrymen, across the Iron Bridge, and encamped himself in front of the

little fort of Tel-Aqibrin, at the eastern edge of the plain of Sarmeda, where

the broken country afforded a good natural defence. Though his forces were far

inferior to the enemy’s, he hoped that he could wait here till Baldwin arrived.

Ilghazi, at Qinnasrin, was perfectly informed

of Roger’s movements. Spies disguised as merchants had inspected the Frankish

camp and reported the numerical weakness of the Frankish army. Though Ilghazi

wished to wait for Toghtekin’s arrival, his Turcoman emirs urged him to take

action. On 27 June part of his army moved to attack the Frankish castle of

Athareb. Roger had time to rush some of his men there, under Robert of

Vieux-Ponts; then, disquieted to find the enemy so close, when darkness fell he

sent away all the treasure of the army to the castle of Artah on the road to

Antioch.

Throughout the

night Roger waited anxiously for news of the Moslems’ movements, while his

soldiers’ rest was broken by a somnambulist who ran through the camp crying that

disaster was upon them. At dawn on Saturday, 28 June, scouts brought word to

the Prince that the camp was surrounded. A dry enervating

khamsin

was

blowing up from the south. In the camp itself there was little food and water.

Roger saw that he must break through the enemy ranks or perish. The Archbishop

of Apamea was with the army, Peter, formerly of Albara, the first Frankish

bishop in the East. He summoned the soldiers together and preached to them and

confessed them all. He confessed Roger in his tent and gave him absolution for

his many sins of the flesh. Roger then boldly announced that he would go

hunting. But first he sent out another scouting-party which was ambushed. The

few survivors hurried back to say that there was no way through the encirclement.

Roger drew up the army in four divisions and one in reserve. Thereupon the

Archbishop blessed them once more; and they charged in perfect order into the

enemy.

It was hopeless from the outset. There was no

escape through the hordes of Turcoman horsemen and archers. The locally

recruited infantrymen, Syrians and Armenians, were the first to panic; but

there was no place to which they could flee. They crowded in amongst the

cavalry, hindering the horses. The wind suddenly turned to the north and rose,

driving a cloud of dust into the Franks’ faces. Early in the battle less than a

hundred horsemen broke through and joined up with Robert of Vieux-Ponts, who

had arrived back from Athareb too late to take part. They fled on to Antioch. A

little later Reynald Mazoir and a few knights escaped and reached the little

town of Sarmeda, in the plain. No one else in the army of Antioch survived.

Roger himself fell fighting at the foot of his great jewelled cross. Round him

fell his knights except for a few, less fortunate, who were made prisoners. By

midday it was all over. To the Franks the battle was known as the

Ager

Sanguinis

, the Field of Blood.

1119: Ilghazi

wastes his Victory

At Aleppo, fifteen miles away, the faithful

waited eagerly for news. About noon a rumour came that a great victory was in

store for Islam; and at the hour of the afternoon prayer the first exultant

soldiers were seen to approach. Ilghazi had only paused on the battlefield to

allot the booty to his men, then marched to Sarmeda, where Reynald Mazoir

surrendered to him. Reynald’s proud bearing impressed Ilghazi, who spared his

life. His comrades were slain. The Frankish prisoners were dragged in chains across

the plain behind their victors. While Ilghazi parleyed with Reynald, they were

tortured and massacred amongst the vineyards by the Turcomans, till Ilghazi put

a stop to it, not wishing the populace of Aleppo to miss all the sport. The

remainder were taken on to Aleppo, where Ilghazi made his triumphant entry at

sundown; and there they were tortured to death in the streets.

While Ilghazi feasted at Aleppo in celebration

of his victory, the terrible news of the battle reached Antioch. All expected

that the Turcomans would come up at once to attack the city; and there were no

soldiers to defend it. In the crisis the Patriarch Bernard took command. His

first fear was of treason from the native Christians, whom his own actions had

done so much to alienate. He at once sent round to disarm them and impose a

curfew on them. Then he distributed the arms that he could collect among the

Frankish clergy and merchants and set them to watch the walls. Day and night

they kept vigil, while a messenger was sent to urge King Baldwin to hurry

faster.

But Ilghazi did not follow up his victory. He

wrote round to the monarchs of the Moslem world to tell them of his triumph;

and the Caliph in return sent him a robe of honour and the title of Star of

Religion. Meanwhile he marched on Artah. The Bishop who was in command of one

of the towers surrendered it in return for a safe-conduct to Antioch; but a

certain Joseph, probably an Armenian, who was in charge of the citadel, where

Roger’s treasure was housed, persuaded Ilghazi that he himself sympathized with

the Moslems, but his son was a hostage at Antioch. Ilghazi was impressed by the

story, and left Artah in Joseph’s hands, merely sending one of his emirs to

reside as his representative in the town. From Artesia he returned to Aleppo,

where he settled down to so pleasant a series of festivities that his health

began to suffer. Turcoman troops were sent to raid the suburbs of Antioch and

sack the port of Saint Symeon, but reported that the city itself was well

garrisoned. The fruits of the Field of Blood were thus thrown away by the

Moslems.

1119: Drawn

Battle at Hab

Nevertheless the position was serious for the

Franks. Baldwin had reached Lattakieh, with Pons close behind him, before he

heard the news. He hurried on, not stopping even to attack an undefended

Turcoman encampment near to the road, and arrived without incident at Antioch

in the first days of August. Ilghazi sent some of his troops to intercept the

relieving army; and Pons, following a day’s march behind, had to ward off their

attack but was not much delayed. The King was received with joy by his sister,

the widowed Princess Cecilia, by the Patriarch and by all the people; and a

service giving thanks to God was held in St Peter’s Cathedral. He first cleared

the suburbs of marauders, then met the notables of the city to discuss its

future government. The lawful prince, Bohemond II, whose ultimate rights Roger

had always acknowledged, was a boy of ten, living with his mother in Italy.

There was no representative of the Norman house left in the East; and the

Norman knights had all perished on the Field of Blood. It was decided that

Baldwin, as overlord of the Frankish East, should himself take over the

government of Antioch till Bohemond came of age, and that Bohemond should then

be married to one of the King’s daughters. Next, Baldwin redistributed the

fiefs of the principality, left empty by the disaster. Wherever it was

possible, the widows of the fallen lords were married off at once to suitable

knights in Baldwin’s army or to newcomers from the West. We find the two

Dowager Princesses, Tancred’s widow, now Countess of Tripoli, and Roger’s

widow, installing new vassals on their dower-lands. At the same time Baldwin

probably rearranged the fiefs of the county of Edessa; and Joscelin, who

followed the King up from Palestine, was formally established as its Count.

Having assured the administration of the land, and having headed a barefoot

procession to the cathedral, Baldwin led his army of about seven hundred

horsemen and some thousand infantrymen out against the Moslems.

Ilghazi had now been joined by Toghtekin; and

the two Moslem chieftains set out on 11 August to capture the Frankish

fortresses east of the Orontes, beginning with Athareb, whose small garrison at

once surrendered in return for a safe-conduct to Antioch. The emirs next day

went on to Zerdana, whose lord, Robert the Leper, had gone to Antioch. Here

again the garrison surrendered in return for their lives; but they were

massacred by the Turcomans as soon as they emerged from the gates. Baldwin had

hoped to save Athareb; but he had hardly crossed the Iron Bridge before he met

its former garrison. He went on south, and heard of the siege of Zerdana.

Suspecting that the Moslems intended to move southward to mop up the castles

round Maarat an-Numan and Apamea, he hurried ahead and encamped on the 13th at

Tel-Danith, the scene of Roger’s victory in 1115. Early next morning he learnt

that Zerdana had fallen and judged it prudent to retire a little towards

Antioch. Meanwhile Ilghazi had come up, hoping to surprise the Franks as they

slept by the village of Hab. But Baldwin was ready. He had already confessed

himself; the Archbishop of Caesarea had harangued the troops and held up the

True Cross to bless them; and the army was ready for action.

The battle that followed was confused. Both

sides claimed a victory; but in fact the Franks came off the best. Toghtekin

drove back Pons of Tripoli, on the Frankish right wing; but the Tripolitans

kept their ranks. Next to him Robert the Leper charged through the regiment

from Homs and eagerly planned to recapture Zerdana, only to fall into an ambush

and be taken captive. But the Frankish centre and left held their ground, and

at the crucial moment Baldwin was able to charge the enemy with troops that

were still fresh. Numbers of the Turcomans turned and fled; but the bulk of

Ilghazi’s army left the battlefield in good order. Ilghazi and Toghtekin

retired towards Aleppo with a large train of prisoners, and were able to tell

the Moslem world that theirs was the victory. Once again the citizens of Aleppo

were gratified by the sight of a wholesale massacre of Christians, till

Ilghazi, after interrupting the killing to try out a new horse, grew disquieted

at the loss of so much potential ransom-money. Robert the Leper was asked his

price and replied that it was ten thousand pieces of gold. Ilghazi hoped to

raise the price by sending Robert to Toghtekin. But Toghtekin had not yet

satisfied his blood-lust. Though Robert was an old friend of his from the days

of 1115, he himself struck off his head, to the dismay of Ilghazi, who needed

money for his soldiers’ pay.

1119: Failure of

the Ortoqid Campaign

At Antioch soldiers fleeing from Pons’s army

had brought news of a defeat; but soon a messenger arrived for the Princess

Cecilia bearing the King’s ring as token of his success. Baldwin himself did

not attempt to pursue the Moslem army but moved on south to Maarat an-Numan and

to Rusa, which the Munqidhites of Shaizar had occupied. He drove them out but

then made a treaty with them, releasing them from the obligation to pay yearly

dues that Roger had demanded. The remaining forts that the Moslems had

captured, with the exception of Birejik, Athareb and Zerdana, were also

recovered. Then Baldwin returned to Antioch in triumph, and sent the Holy Cross

southward to arrive at Jerusalem in time for the Feast of the Exaltation, on 14

September. He himself spent the autumn in Antioch, completing the arrangements

that he had begun before the recent battle. In December he journeyed back to

Jerusalem, leaving the Patriarch Bernard to administer Antioch in his name, and

installing Joscelin in Edessa.

He brought south with him from Edessa

his wife and their little daughters; and at the Christmas ceremony at Bethlehem

Morphia was crowned queen.

Ilghazi had not ventured to attack the Franks

again. His army was melting away. The Turcoman troops had come mainly for the

sake of plunder. After the battle of Tel-Danith they were left idle and bored

and their pay was in arrears. They began to go home, and with them the Arab

chieftains of the Jezireh. Ilghazi could not prevent them; for he himself had

fallen ill once more and for a fortnight he hung between life and death. When

he recovered it was too late to reassemble his army. He returned from Aleppo to

his eastern capital at Mardin, and Toghtekin returned to Damascus.

Thus the great Ortoqid campaign fizzled out. It

had achieved nothing material for the Moslems, except for a few frontier-forts

and the easing of Frankish pressure on Aleppo. But it had been a great moral

triumph for Islam. The check at Tel-Danith had not counterbalanced the

tremendous victory of the Field of Blood. Had Ilghazi been abler and more

alert, Antioch might have been his. As it was, the slaughter of the Norman

chivalry, their Prince at their head, encouraged the emirs of the Jezireh and

northern Mesopotamia to renew the attack, now that they were free from the

tutelage of their nominal Seldjuk overlord in Persia. And soon a greater man

than Ilghazi was to arise. For the Franks the worst result of the campaign had

been the appalling loss of man-power. The knights and, still more, the

infantrymen fallen on the Field of Blood could not easily be replaced. But the

lesson had now been thoroughly learnt that the Franks of the East must always

co-operate and work as a unit. King Baldwin’s prompt intervention had saved

Antioch; and the needs of the time were recognized by the readiness of all the

Franks to accept him as an active overlord. The disaster welded together the

Frankish establishments in Syria.

On his return to Jerusalem Baldwin busied

himself over the administration of his own kingdom. The succession to the

principality of Galilee was given to William of Bures, in whose family it

remained. In January 1120 the King summoned the ecclesiastics and

tenants-in-chief of the kingdom to a council at Nablus to discuss the moral

welfare of his subjects, probably in an attempt to curb the tendency of the

Latin colonists in the East to adopt the easy and indolent habits that they

found there. At the same time he was concerned with their material welfare.

Under Baldwin I an increasing number of Latins had been encouraged to settle in

Jerusalem, and a Latin bourgeois class was growing up there by the side of the warriors

and clerics of the kingdom. These Latin bourgeois were now given complete

freedom of trade to and from the city, while, to ensure a full supply of food,

the native Christians and even Arab merchants were allowed to bring vegetables

and corn to the city free of customs-dues.