A History of the Crusades-Vol 2 (24 page)

Fulk’s accession raised the whole question. The

opposition to his overlordship was led by Alice, his sister-in-law. She had

submitted to her father, King Baldwin, with a very bad grace. She now

reasserted her claim to be her daughter’s regent. It was not ill-founded, if it

could be maintained that the King of Jerusalem was not overlord of Antioch; for

it was usual, both in Byzantium and in the West, for the mother of a

child-prince to be given the regency. Joscelin I’s death, barely a month after

Baldwin’s, gave her an opportunity; for Joscelin had been guardian of the young

Princess Constance, and the barons at Antioch would not install Joscelin II in

his father’s place. Disappointed, the new Count of Edessa listened to Alice’s

blandishments. He, too, was doubtless unwilling to accept Fulk as his suzerain.

Pons of Tripoli also offered her support. His wife, Cecilia, had received from

her first husband, Tancred, the dower-lands of Chastel Rouge and Arzghan: and

through her he was thus one of the great barons of the Antiochene principality.

He realized that the emancipation of Antioch from Jerusalem would enable

Tripoli to follow suit. Alice had already won over the most formidable barons

in the south of the principality, the brothers, William and Garenton of

Zerdana, Lords of Sahyun, the great castle built by the Byzantines in the hills

behind Lattakieh; and she had her partisans in Antioch itself. But the majority

of the Antiochene lords feared a woman’s rule. When they heard rumours of Alice’s

plot, they sent a messenger to Jerusalem to summon King Fulk.

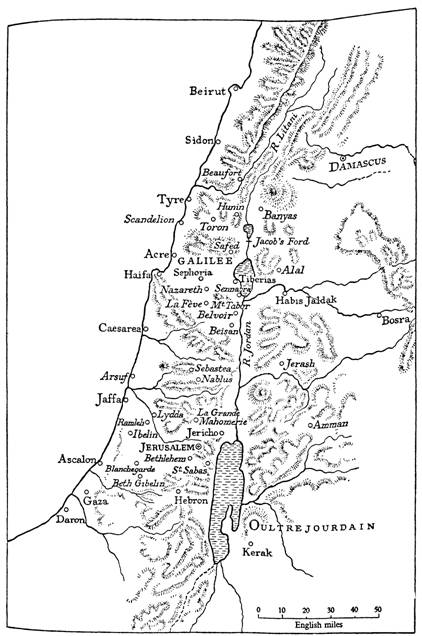

Map 3. The

Kingdom of Jerusalem in the twelfth century.

Fulk set out at once with an army from

Jerusalem. It was a challenge that he could not ignore. When he reached the

confines of Tripoli, Pons refused him passage. The Countess Cecilia was Fulk’s

half-sister; but Fulk’s appeal to the duties of kinship was made in vain. The

army of Jerusalem had to proceed by sea, from Beirut to Saint Symeon. As soon

as he landed in Antiochene territory the King marched southward and defeated

the rebel allies at Chastel Rouge. But he was not strong enough to punish his

enemies. Pons apologized to him and was reconciled. Alice remained unharmed at

Lattakieh, in her dower-lands. The brothers William and Garenton of Sahyun were

forgiven, as was Joscelin of Edessa; who had not been present in the battle. It

is doubtful whether Fulk obtained an oath of allegiance from either Pons or

Joscelin; nor did he succeed in breaking up Alice’s party. William of Sahyun

was killed a few months later, in the course of a small Moslem raid against

Zerdana; and Joscelin promptly married his widow Beatrice, who probably brought

him Zerdana as her dower. But for the meantime peace was restored. Fulk himself

retained the regency of Antioch but entrusted its administration to the

Constable of the principality, Reynald Mazoir, lord of Marqab. He himself

returned to Jerusalem, to take part in a terrible drama at the Court.

1132: Hugh of Le

Puiset and Queen Melisende

There was amongst his nobles a handsome youth,

Hugh of Le Puiset, lord of Jaffa. His father, Hugh I of Le Puiset in the

Orleannais, a first cousin of Baldwin II, had been the leader of the baronial

opposition to King Louis VI of France; who in 1118 destroyed the castle of Le

Puiset and deprived him of his fief. Hugh’s brothers Gildoin, abbot of Saint

Mary Josaphat, and Waleran of Birejik had already gone to the East and, as

Baldwin had recently become King of Jerusalem, Hugh decided to follow them with

his wife Mabilla. They set out with their young son Hugh. As they passed

through Apulia the boy fell ill; so they left him there at the Court of

Bohemond II, who was Mabilla’s first cousin. On their arrival in Palestine they

were given by Baldwin the lordship of Jaffa. Hugh I died soon afterwards,

whereupon Mabilla and the fief passed to a Walloon knight, Albert of Namur.

Both Mabilla and Albert soon followed him into the grave; and Hugh II, now aged

about sixteen, sailed from Apulia to claim his heritage. Baldwin received him

well and handed his parents’ fief over to him; and he was brought to live at

the royal Court, where his chief companion was his cousin, the young Princess

Melisende. About 1121 he married Emma, niece of the Patriarch Arnulf and widow

of Eustace Gamier, a lady of mature age but of vast possessions. She delighted

in her tall, handsome husband; but her twin sons, Eustace II, heir of Sidon,

and Walter, heir of Caesarea, hated their stepfather who was little older than

themselves. Meanwhile Melisende was married to Fulk, for whom she never cared,

despite his great love for her. After her accession she continued her intimacy

with Hugh. There was gossip at the Court; and Fulk grew jealous. Hugh had many

enemies, headed by his stepsons. They fanned the King’s suspicions, till at

last Hugh in self-defence gathered round him a party of his own, of which the

leading member was Roman of Le Puy, lord of the lands of Oultrejourdain. Soon

all the nobility of the kingdom was divided between the King and the Count, who

was known to have the sympathy of the Queen. Tension grew throughout the summer

months of 1132. Then one day in the late summer, when the palace was full of

the magnates of the realm, Walter Gamier stood up and roundly accused his

stepfather of plotting against the life of the King, and challenged him to

justify himself in single combat. Hugh denied the charge and accepted the

challenge. The date for the duel was fixed by the High Court; and Hugh retired

to Jaffa and Walter to Caesarea, each to prepare himself.

When the day arrived, Walter was ready at the

lists, but Hugh stayed away. Perhaps the Queen, alarmed that things had gone

too far, begged him to absent himself, or perhaps it was the Countess Emma,

appalled at the prospect of losing either husband or son; or perhaps Hugh

himself, knowing his guilt, was afraid of God’s vengeance. Whatever its cause

might be, his cowardice was read as the proof of his treason. His friends could

support him no longer. The King’s council declared him guilty by default. Hugh

then panicked and fled to Ascalon to ask for protection from the Egyptian

garrison. An Egyptian detachment brought him back to Jaffa and from there began

to ravage the plain of Sharon. Hugh’s treason was now overt. His chief vassal,

Balian, lord of Ibelin and Constable of Jaffa, turned against him; and when a

royal army came hastily down from Jerusalem, Jaffa itself surrendered without a

blow. Even the Egyptians abandoned Hugh as a profitless ally. He was obliged to

make his submission to the King.

His punishment was not severe. The Queen was

his friend, and the Patriarch, William of Messines, counselled mercy. The King

himself was anxious to smooth things over; for already the dangers of civil war

had been made clear. On 11 December, when the royal army had been summoned to

march against Jaffa, the atabeg of Damascus had surprised the fortress of

Banyas and recovered it for Islam. It was decided that Hugh should go for three

years into exile; then he might return with impunity to his lands.

1132: Attempted

Murder of Hugh

While awaiting a boat for Italy, Hugh came up

to Jerusalem early in the new year to say good-bye to his friends. As he was

playing dice one evening at the door of a shop in the Street of the Furriers, a

Breton knight crept up behind him and stabbed him through his head and through

his body. Hugh was carried off bleeding to death. Suspicion at once fell upon

the King; but Fulk acted promptly and prudently. The knight was handed over for

trial by the High Court. He confessed that he had acted on his own initiative,

hoping thus to win the favour of the King, and was sentenced to death by having

his limbs cut off one by one. The execution took place in public. After the

victim’s arms and legs had been struck off but while his head remained to him

he was made to repeat his confession. The King’s reputation was saved. But the

Queen was not satisfied. So angry was she with Hugh’s enemies that for many

months they feared assassination; and their leader, Raourt of Nablus, dared not

walk in the streets without an escort. Even King Fulk was said to be afraid for

his life. But his one desire was to win his wife’s favour. He gave way to her

in everything; and she, thwarted in love, soon found consolation in the

exercise of power.

Hugh survived his attempted murder, but not for

long. He retired to the Court of his cousin, King Roger II of Sicily, who

enfeoffed him with the lordship of Gargano, where he died soon afterwards.

It was no doubt with relief that Fulk turned

his attention once more to the north. The situation there was more ominous for

the Franks than in Baldwin II’s days. There was no effective prince ruling in

Antioch. Joscelin II of Edessa lacked his father’s energy and political sense.

He was an unattractive figure. He was short and thick-set, dark-haired and

dark-skinned; his face was pock-marked, with a huge nose and prominent eyes. He

was capable of generous gestures, but was lazy, luxurious and lascivious, and

quite unfitted to command the chief outpost of Frankish Christendom.

1133: Fulk

rescues Pons of Tripoli

The dearth of leadership among the Franks was

the more serious because the Moslems now had in Zengi a man capable of

assembling the forces of Islam. As yet Zengi was biding his time. He was too

heavily entangled in events in Iraq to take advantage of the situation among

the Franks. The Sultan Mahmud ibn Mohammed died in 1131, leaving his

possessions in Iraq and southern Persia to his son Dawud. But the dominant

member of the Seldjuk family, Sanjar, decided that the inheritance should pass

to Mahmud’s brother Tughril, lord of Kazwin. The other two brothers of Mahmud,

Mas’ud of Fars and Seldjuk-Shah of Azerbaijan, then put in claims. Dawud soon

retired, supported neither by Mustarshid nor by his subjects. For a while

Tughril, armed by Senjar’s influence, was accepted at Baghdad; and Mas’ud was

forced by Sanjar to retire. But Sanjar soon lost interest; whereupon

Seldjuk-Shah came to Baghdad and won the Caliph’s support. Mas’ud appealed to

Zengi to help him. Zengi marched on Baghdad, only to be severely defeated by

the Caliph and Seldjuk-Shah near Tekrit. Had not the Kurdish governor of

Tekrit, Najm ed-Din Ayub, conveyed him across the river Tigris, he would have

been captured or slain. Zengi’s defeat encouraged the Caliph, who now dreamed

to resurrect the past power of his house. Even Sanjar was alarmed; and Zengi as

his representative once again attacked Baghdad in June 1132, this time in

alliance with the volatile Bedouin chieftain, Dubais. In the battle that

followed Zengi was at first victorious; but the Caliph intervened in person,

routed Dubais and turned triumphantly on Zengi, who was forced to retire to

Mosul. Mustarshid arrived there next spring at the head of a great army. It

seemed that the Abbasids were to recover their old glory; for the Seldjuk

Sultan of Iraq was now little more than a client of the Caliph. But Zengi

escaped from Mosul and began relentlessly to harass the Caliph’s camp and to

cut off his supplies. After three months Mustarshid retired.

The

Abbasid revival was cut short. During the next year the Seldjuk prince Mas’ud

gradually displaced the other claimants to the Sultanate of Iraq. Mustarshid

vainly tried to check him. At a battle at Daimarg in June 1135 the Caliph’s

army was routed by Mas’ud and he himself captured. He was sent into exile to

Azerbaijan and there was murdered by Assassins, probably with Mas’ud’s

connivance. His son and successor in the Caliphate, Rashid, appealed to the

Seldjuk claimant Dawud and to Zengi, but in vain. Mas’ud secured Rashid’s

deposition by the cadis at Baghdad. His successor, Moqtafi, managed by lavish

promises to seduce Zengi away from Rashid and Dawud. Fortified by fresh titles

of honour from Moqtafi and from Mas’ud, Zengi was able, from 1135 onwards, to

turn his attention to the West.

While Zengi was engaged in Iraq, his interests

in Syria were cared for by a soldier from Damascus, Sawar, whom he made

governor of Aleppo. He could not afford to send him many troops; but at his

instigation various bodies of freebooting Turcomans entered Sawar’s services,

and with them Sawar prepared in the spring of 1133 to attack Antioch. King Fulk

was summoned by the frightened Antiochenes to their rescue. As he journeyed

north with his army he was met at Sidon by the Countess of Tripoli, who told

him that her husband had been ambushed by a band of Turcomans in the Nosairi

mountains and had fled to the castle of Montferrand, on the edge of the Orontes

valley. At her request Fulk marched straight to Montferrand; and on his

approach the Turcomans retired. The episode restored cordial relations between

Fulk and Pons. Soon afterwards Pons’s son and heir Raymond was married to the

Queen’s sister, Hodierna of Jerusalem; while his daughter Agnes married the son

of Fulk’s constable at Antioch, Reynald Mazoir of Marqab.