A History of the Crusades-Vol 2 (54 page)

Reynald and his friends persuaded the King to

concentrate the royal army in Oultrejourdain, to catch Saladin as he came up

from Egypt. The Ibelins and Raymond vainly pointed out that this would expose

Palestine to him should he get by. Saladin left Egypt on 11 May 1182. As he

bade a ceremonious farewell to his ministers, a voice from the crowd shouted

out a line of poetry whose meaning was that he would never see Cairo again. The

prophecy came true. He took his army across the Sinai desert to Akaba, and

moved northward without difficulty, well to the east of the Frankish army, destroying

the crops as he went. When he arrived at Damascus he found that Faruk-Shah had

already raided Galilee and sacked the villages on the slopes of Mount Tabor,

taking twenty thousand head of cattle and one thousand prisoners. On his return

Faruk-Shah attacked the fortress of Habis Jaldak, carved out of the rock above

the river Yarmuk beyond the Jordan. A tunnel that he cut through the rock put

it at his mercy; and the garrison, Christian Syrians with no great wish to die

for the Franks, promptly surrendered. Saladin spent three weeks in Damascus,

then with Faruk-Shah and a large army left on 11 July and crossed into

Palestine round the south of the Sea of Galilee. The King, aware now of the

folly of his previous strategy, had come back from Oultrejourdain and marched

up the west bank of the river, bringing the Patriarch and the True Cross to

bless his arms. The two armies met beneath the Hospitallers’ castle of Belvoir.

In the fierce battle that followed the Franks held their ground against Saladin’s

attacks, but their counter-attacks did not break the Moslem lines. At the end

of the day each side retired, claiming the victory.

1181: Death of

as-Salih

It had been a check for Saladin as the invader,

but only temporary. In August he once again crossed the frontier in a lightning

march through the mountains to Beirut. At the same moment his fleet, summoned

from Egypt by the pigeon-post that operated between Damascus and Cairo,

appeared off the coast. But Beirut was well fortified; and its bishop, Odo,

organized a brave, vigorous defence. Baldwin, on the news, rushed his army up

from Galilee, only pausing to collect the ships that lay in the harbours of

Acre and Tyre. Failing to take the city by assault before the Franks arrived,

Saladin withdrew. It was time for him to deal with business that was more

urgent.

Saif ed-Din of Mosul died on 29 June 1180,

leaving only young children. The emirs of Mosul invited his brother, Izz

ed-Din, to succeed him. Eighteen months later, on 4 December 1181, as-Salih of

Aleppo died suddenly of a colic, universally attributed to poison. He was only

eighteen, a bright, intelligent boy who might have been a great ruler. On his

death-bed he begged his emirs to offer the succession to his cousin of Mosul,

so as to unite the family lands against Saladin. Izz ed-Din arrived at Aleppo

at the end of the year and was given an enthusiastic welcome. Messengers came

from the emir of Hama to offer him allegiance. But the two years’ truce with

Saladin had not run out; and Izz ed-Din refused their offer, more from

indolence than from honour. He had enough to worry him: for in February 1182

his brother Imad ed-Din of Sinjar claimed a share in the inheritance and

intrigued with the commander of the army of Aleppo, Kukburi. In May Izz ed-Din

returned to Mosul, and Imad ed-Din gave him Sinjar in return for Aleppo.

Kukburi was rewarded with the emirate of Harran. From there he plotted with his

Ortoqid neighbours, the princes of Hisn Kaifa and Birejik, against the princes

of Aleppo and Mosul and the Ortoqid Qutb ed-Din of Mardin; and the conspirators

called Saladin to their aid. The truce among the Moslem princes ended in

September. The day that it was over Saladin crossed the frontier and after a

feint attack on Aleppo he moved over the Euphrates at Birejik. The towns of the

Jezireh fell before him, Edessa, Saruj, and Nisibin. He pressed on to Mosul and

began the siege of the city on 10 November. Once again he was thwarted by

fortifications too strong to storm. His spiritual master, the Caliph an-Nasir,

shocked at this war between fellow-Moslems, tried to negotiate a peace. The

Seldjuk ruler of Persarmenia and the Prince of Mardin prepared to send a

relieving force. So Saladin retired to Sinjar, which he took by storm after a

fortnight’s siege. For once he was unable to restrain his soldiers from

pillaging the city; but he released the governor and sent him honourably

attended to Mosul. Izz ed-Din and his allies marched out to meet him near

Mardin, but sent ahead to suggest a truce. When Saladin answered truculently

that he would meet them on the battlefield, they dispersed and fled to their

homes. He did not pursue them, but went north to conquer Diarbekir, the richest

and greatest fortress of the Jezireh, with the finest library in Islam. He gave

the city to the Prince of Hisn Kaifa. After reorganizing the Jezireh, setting

each city to be held as a fief under an emir that he trusted, he appeared

again, on 21 May, before Aleppo.

1183: Saladin

takes possession of Aleppo

When Saladin moved against them, both Imad

ed-Din and Izz ed-Din had sought help from the Franks. An embassy from Mosul

promised them a yearly subsidy of 10,000 dinars, with the retrocession of

Banyas and Habis Jaldak, and the release of any Christian prisoner that might

be found in Saladin’s possession, if they would make a diversion against

Damascus. It was a hopeful moment; for a few days after Saladin invaded the

Jezireh, his nephew Faruk-Shah, governor of Damascus, suddenly died. King

Baldwin, accompanied by the Patriarch and the True Cross, thereupon led a raid

through the Hauran, which sacked Ezra and reached Bosra, while Raymond of

Tripoli recaptured Habis Jaldak. Early in December 1182 Raymond led a cavalry

raid that again penetrated to Bosra; and a few days later the royal army set

out against Damascus and encamped at Dareiya in the suburbs. It has a famous

mosque, which Baldwin spared after receiving a delegation from the Christians

of Damascus warning that reprisals would be taken against their churches should

it be harmed. The King did not try to attack the city itself, and soon retired

laden with booty, to spend Christmas at Tyre. He planned a further campaign for

the spring, but early in the new year he fell desperately ill of a fever at

Nazareth. For some weeks he lay between life and death; and his disease

immobilized his army. Farther north, Bohemond III was powerless to take any

action against Saladin. He sent to his camp before Aleppo and concluded a four

years’ truce with him. It enabled him to repair the defences of his capital.

At Aleppo Imad ed-Din made little effort to

oppose Saladin. He was unpopular there; and when Saladin offered to give him

his old home at Sinjar together with Nisibin, Saruj and Rakka, to hold as a

fief, he gladly complied. On 12 June 1183 Saladin took possession of Aleppo.

Five days later Imad ed-Din departed for Sinjar, honourably escorted, but

mocked by the crowds of the city that he abandoned so lightly. On 18 June

Saladin made his formal entry and rode up to the castle.

On 24 August the Sultan returned to Damascus,

which was to be his capital. His Empire now stretched from Cyrenaica to the

Tigris. For more than two centuries past there had not been so powerful a

Moslem prince. He had the wealth of Egypt behind him. The great cities of

Damascus and Aleppo were under his direct government. Around them and

north-eastward as far as the walls of Mosul were military fiefs on whose rulers

he could rely. The Caliph at Baghdad supported him. Izz ed-Din at Mosul was

cowed by him. The Seldjuk Sultan in Anatolia sought his friendship, and the

Seldjuk princes of the East were powerless to oppose him. The Christian Empire

of Byzantium was no longer a danger to him. It only remained now to suppress

the alien intruders whose possession of Palestine and the Syrian littoral was a

lasting shame to Islam.

CHAPTER II

THE HORNS OF

HATTIN

‘Our end is near

,

our

days are fulfilled; for our end is come.’

LAMENTATIONS IV, 18

When King Baldwin rose from his sick-bed at

Nazareth it was clear that he would no more be able to govern the country. His

leprosy had been aggravated by his fever. He had lost the use of his arms and

legs; and they were beginning to decay. His sight had almost gone. His mother,

his sister Sibylla and the Patriarch Heraclius kept guard over him and

persuaded him to hand the regency to Sibylla’s husband, Guy of Lusignan. Guy

was to be in complete control of the kingdom, except only the city of

Jerusalem, which, with a revenue of 10,000 besants, the King reserved for

himself. The barons of the realm reluctantly accepted the King’s decision.

1182: Reynald’s

Red Sea Expedition

Reynald of Chatillon was absent from these

deliberations. When he heard of Saladin’s departure to the north in the autumn

of 1182, he set in motion a project that he had long had in mind, to launch a

squadron on the Red Sea to raid the rich sea-caravans to Mecca and even to

attack the Holy City of Islam itself. Towards the end of the year he marched

down to Aila at the head of the Gulf of Akaba, bringing galleys that he built

with timber from the forests of Moab and tried out on the waters of the Dead

Sea. Aila, which had been held by the Moslems since 1170, fell to him; but the

fortress on the island close by, the Ile de Graye of the Frankish historians,

held out; and Reynald remained with two of his ships to blockade it. The rest

of his fleet set gaily out, with local pirates to pilot them. They sailed down

the African coast of the Red Sea, raiding the little coastal towns that they

passed, and eventually attacked and sacked Aidib, the great Nubian port

opposite to Mecca. There they captured richly laden merchant ships from Aden

and from India; and a landing-party pillaged a huge defenceless caravan that

had come over the desert from the Nile valley. From Aidib the corsairs crossed

over to the Arabian coast. They burnt the shipping at al-Hawra and Yambo, the

ports of Medina, and penetrated to ar-Raghib, one of the ports of Mecca itself.

Close by they sank a pilgrim-ship bound for Jedda. The whole Moslem world was

horrified. Even the Princes of Aleppo and Mosul, who had called upon Frankish

help, were ashamed to have allies that planned such an outrage on the Faith.

Saladin’s brother Malik al-Adil, governor of Egypt, took action. He sent the

Egyptian admiral, Husam ed-Din Lulu, with a fleet manned by Maghrabi sailors

from North Africa, in pursuit of the Franks. Lulu first relieved the castle of

Graye and recaptured Aila, from which Reynald himself had already retired; then

he caught up with the corsair fleet off al-Hawra, destroying it and capturing

almost all the men on board. A few of them were sent to Mecca, to be

ceremoniously executed at the Place of Sacrifice at Mina during the next

Pilgrimage. The rest were taken to Cairo, and there they were beheaded. Saladin

vowed solemnly that Reynald should never be forgiven for his attempted outrage.

The Horns of

Hattin

On 17 September 1183 Saladin left Damascus with

a great army to invade Palestine. On the 29th he crossed the Jordan, just south

of the Sea of Galilee and entered Beisan, whose inhabitants had all fled to the

safety of the walls of Tiberias. On the news of his coming Guy of Lusignan

summoned the full force of the kingdom, strengthened by two rich visiting

Crusaders, Godfrey III, Duke of Brabant, and the Aquitanian Ralph of Mauleon,

and their men. With Guy were Raymond of Tripoli, the Grand Master of the

Hospital, Reynald of Chatillon, the Ibelin brothers, Reynald of Sidon and

Walter of Caesarea. Young Humphrey IV of Toron came to join them with his

stepfather’s forces from Oultrejourdain; but he was ambushed by the Moslems on

the slopes of Mount Gilboa, and most of his men were slain. Saladin then sent

detachments to capture and destroy the little forts of the neighbourhood, while

others sacked the Greek convent on Mount Tabor but failed to break through the

strong walls of the Latin establishment on the summit of the hill. He himself

encamped with his main army by the fountain of Tubaniya, on the site of the

ancient city of Jezreel.

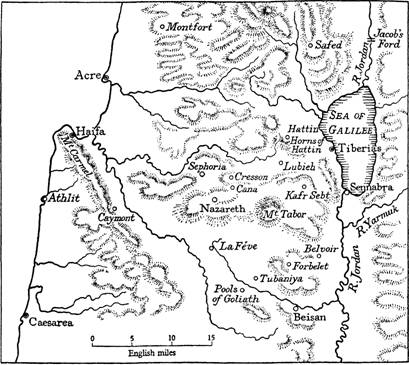

Map 6. Galilee.

1183: Guy

quarrels with the King

The Franks had assembled at Sephoria and

marched on into the plain of Jezreel on 1 December. The advance-guard, under

the Constable Amalric, was at once attacked by the Moslems, but the timely

arrival of the Ibelins with their troops rescued it. The Christians encamped at

the Pools of Goliath opposite to Saladin, who then extended his wings so as almost

to encircle them. For five days the armies remained stationary. It was

difficult for supplies to come through to the Christians. After a day or two

the Italian mercenaries complained of hunger; and only the timely discovery of

fish in the Pools of Goliath saved the army from starvation. Most of the

soldiers, including the knights from France and the irrepressible Reynald,

wished to attack the Moslems. Guy hesitated and dithered; but Raymond and the

Ibelins firmly insisted that to provoke a fight against such superior numbers

would be fatal. The army must remain on the defensive. They were right. Saladin

many times tried to lure them out. When he failed he lifted his camp on 8

October and moved back behind the Jordan.