A History of the World in 100 Objects (54 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

The Spain in which this astrolabe was made was the only place in Christian-ruled Europe where there were significant populations of Muslims; it was also home to an extensive Jewish population. From the eighth to the fifteenth centuries, the mixing in medieval Spain of the people of these three religions was one of Spanish society’s most distinctive elements. Of course, there was no such country as Spain yet – in the fourteenth century it was still a patchwork of states. The biggest was Castile, which shared a border with the last independent Muslim state in the peninsula, the kingdom of Granada. In many parts of Christian Spain there were large numbers of Jews and Muslims, all three groups living together but keeping their separate traditions, in what might be described as an early example of multiculturalism. This coexistence, extremely rare in this period of European history, is often referred to by the Spanish term

convivencia

.

The distinguished historian of Spain Professor Sir John Elliott explains how this mixed society emerged:

As I see it, the essence of multiculturalism is the preservation of the distinctive identity of the different religious and ethnic communities in a society. And for much of the period of Islamic rule, the policy of the rulers was to accept that diversity, even if it regarded Christians and Jews as adherents of inferior faiths. When the Christian rulers took over they did much the same, because they had no other option, really, though at the same time, of course, intermarriage was forbidden within these communities, so it was a limited multiculturalism. That didn’t prevent a great deal of mutual interaction, particularly at the cultural level. So the result was a civilization which was vibrant and creative and original because of this contact between the three races.

A couple of centuries earlier this mutual interaction had put medieval Spain at the forefront of the expansion of knowledge in Europe. Not only was there growing scientific knowledge around astronomical instruments like our astrolabe, but it was also in Spain that the works of the ancient Greek philosophers, above all Aristotle, were translated into Latin and entered the intellectual bloodstream of medieval Europe. This pioneering work depended on constant interchange between Muslim, Jewish and Christian scholars, and by the fourteenth century, this scholarly legacy was embedded in European thought – in science and medicine as well as philosophy and theology. The astrolabe became the indispensable tool of astronomers, astrologers, doctors, geographers or indeed anyone with intellectual aspirations – even a ten-year-old English boy like Chaucer’s son. Eventually, this one intricate object that could do so many things would be displaced by a whole range of separate instruments – the globe, the printed map, the sextant, the chronometer and the compass, each doing one of the numerous jobs the astrolabe could do on its own.

The shared inheritance of Islamic, Christian and Jewish thinkers would survive for centuries, but the

convivencia

of the three faiths did not. Although medieval Spain is today often hailed by politicians as a beacon of tolerance and the model for multi-faith coexistence, the historical truth is distinctly less comfortable. This is Sir John Elliott again:

As regards actual religious tolerance, it’s rather less clear-cut than coexistence … Christendom in general was a pretty intolerant society, very opposed to deviants of all kinds, and that intolerance was particularly directed against the Jews. For instance, England expelled its Jews in 1290, and France more than a decade later, and as far as Christian–Muslim relations were concerned there was a hardening of religious attitudes from the twelfth century onwards. As the Christians preached the Crusades, and the Almohads who moved into Spain from North Africa preached the Jihad, there was an increasing aggressiveness on both sides

.

Against this background, Christian Spain could still seem comparatively tolerant. But there were already signs of trouble, and the survival of Muslim Granada was a reminder of unfinished business. The intellectual alliance of Christians, Jews and Muslims would soon be swept away by a militant Spanish monarchy, intent on following the rest of Europe and asserting Christian dominance. In the years around 1500, Jews and Muslims would be persecuted and expelled from Spain. The

convivencia

was over.

Ife Head

1400–1500

AD

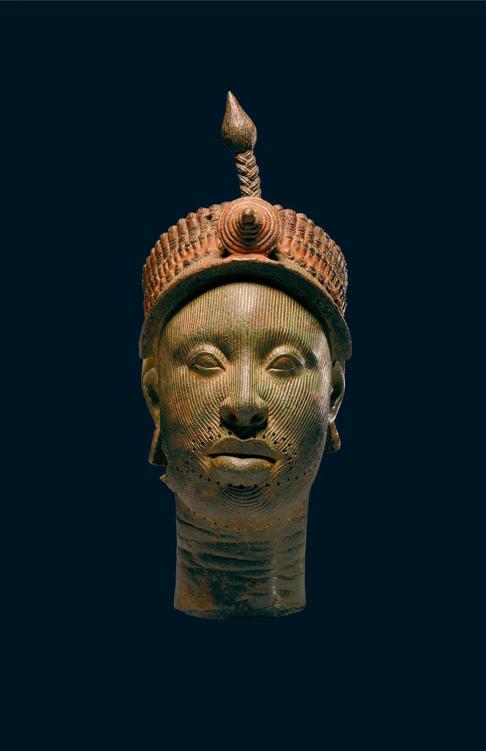

So far in this history of the world through things, we have encountered all kinds of objects, all eloquent, but many of them neither beautiful nor valuable. This object, however, a head cast in brass, is undoubtedly a great work of art. It is quite clearly the portrait of a person – though we don’t know who; it is without question by a very great artist – though we don’t know who; and it must have been made for a ceremony – though we don’t know what kind. What is certain is that the head is African, it is royal, and it epitomizes the great medieval civilizations of West Africa of about 600 years ago. It is one of a group of thirteen heads, superbly cast in brass, all discovered in 1938 in the grounds of a royal palace in Ife, Nigeria, which astonished the world with their beauty. They were immediately recognized as supreme documents of a culture that had left no written record, and they embody the history of an African kingdom that was one of the most advanced and urbanized of its day. The sculptures of Ife exploded European notions of the history of art, and they forced Europeans to rethink Africa’s place in the cultural history of the world. Today they play a key part in how Africans read their own narrative.

The Ife head is in the Africa gallery of the Museum, where it seems to be looking at its visitors. It is a little smaller than life-size and is made of brass, which has darkened with age. The shape of the face is an elegant oval, covered with finely incised vertical lines – but it is a facial scarring so perfectly symmetrical that it contains rather than disturbs the features. He wears a crown – a high beaded diadem with a striking vertical plume projecting from the top, which still has quite a lot of the original red paint. This is an object with extraordinary presence. The alert gaze, the high curve of the cheek, the lips parted as though about to speak – all these are captured with absolute confidence. To grasp the structure of a face like this is possible only after long training and meticulous observation. There is no doubt that this represents a real person, and reality not just rendered but transformed. The details of the face have been generalized and abstracted to give an impression of repose. Standing face to face with this brass sculpture I know that I’m in the presence of a ruler imbued with the high serenity of power. When Ben Okri, the Nigerian-born novelist, looks at the Ife head he sees not only a ruler but a society and a civilization:

It has the effect on me that certain sculptures of the Buddha have. The presence of tranquillity in a work of art speaks of a great internal civilization, because you can’t have tranquillity without reflection, without having asked the great questions about your place in the universe and having answered those questions to some degree of satisfaction. That for me is what civilization is.

The idea of black African civilization on this level was quite simply unimaginable to a European a hundred years ago. In 1910, when the German anthropologist Leo Frobenius found the first brass head in a shrine outside the city of Ife, he was so overwhelmed by its technical and aesthetic assurance that he immediately associated it with the greatest art that he knew – the Classical sculptures of ancient Greece. But what possible connection could there have been between ancient Greece and Nigeria? There’s no record of contact in the literature or in the archaeology. For Frobenius there was an obvious and exhilarating solution to the conundrum: the lost island of Atlantis must have sunk off the coast of Nigeria and the Greek survivors stepped ashore to make this astonishing sculpture.

It’s easy to mock Frobenius, but at the beginning of the twentieth century Europeans had very limited knowledge of the traditions of African art. For painters like Picasso, Nolde or Matisse, African art was Dionysiac, exuberant and frenetic, visceral and emotional. But the restrained, rational, Apollonian sculptures of Ife clearly came from an orderly world of technological sophistication, sacred power and courtly hierarchy, a world in every way comparable with the historic societies of Europe and Asia. As with all great artistic traditions, the sculptures of Ife present a particular view of what it means to be human. Babatunde Lawal, Professor of Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University, explains:

Frobenius around 1910 assumed that the survivors of the Greek lost Atlantis might have made these heads, and he predicted that if a full figure were to be found, the figure would reflect the typical Greek proportions, the head constituting about one seventh of the whole body. But when a full figure was eventually discovered at Ife the head was just about a quarter of the body, complying with the typical proportion characterizing much of African art – the emphasis on the head because it is the crown of the body, the seat of the soul, the site of identity, perception and communication.

Given this traditional emphasis, it is perhaps not surprising that nearly all of the Ife metal sculptures that we know – and there are only about thirty – are heads. The discovery of thirteen of those heads in 1938 meant there could no longer be any doubt that this was a totally African tradition. The

Illustrated London News

of 8 April 1939 reported the find. In an extraordinary article, the writer, still using the conventional (to us, racist) language of the 1930s, recognizes that what he calls the Negro tradition – a word then associated with slavery and primitivism – must, with the Ife sculptures, now take its place in the canon of world art. The word ‘Negro’ could never again be used in quite the same way.

One does not have to be a connoisseur or an expert to appreciate the beauty of their modelling, their virility, their reposeful realism, their dignity and their simplicity. No Greek or Roman sculpture of the best periods, not Cellini, not Houdon, ever produced anything that made a more immediate appeal to the senses or is more immediately satisfying to European ideas of proportion.

It is hard to exaggerate what a profound reversal of prejudice and hierarchy this represented. Along with Greece and Rome, Florence and Paris, now stood Nigeria. If you want an example of how things can change thought, the impact of the Ife heads in 1939 are I think as good as you’ll find.

Recent research suggests that the heads we know were all made over quite a short stretch of time, possibly in the middle of the fifteenth century. At that point Ife had already been a leading political, economic and spiritual centre for centuries. It was a world of forest farming dominated by cities, which developed in the lands west of the Niger river. And it was river networks that connected Ife to the regional trade networks of West Africa and to the great routes that carried ivory and gold by camel across the Sahara to the Mediterranean coast. In return came the metals that would make the Ife heads. The world of the Mediterranean had provided not the artists, as Frobenius supposed, merely the raw materials.

The forest cities were presided over by their senior ruler, the Ooni of Ife. The Ooni’s role was not just political – he also had a great range of spiritual and ritual duties, and the city of Ife has always been the leading religious centre of the Yoruba people. There is still an Ooni today. He has high ceremonial status and moral authority, and his headgear still echoes that of the sculpted head of about 600 years ago.

Our head is almost certainly the portrait of an Ooni, but it is not at all obvious how such a portrait would have been used. It was clearly not meant to stand on its own, so it might well have been mounted on a wooden body – there is what looks like a nail hole at the neck that could have been used to attach it. It has been suggested that it might have been carried in processions or that in certain ceremonies it could have stood in for an absent or even for a dead Ooni.

Around the mouth there are a series of small holes. Again, we can’t be quite certain what these are for, but they were possibly used to attach a beaded veil that would hide the mouth and the lower part of the face. We know that the Ooni today still covers his face completely on some ritual occasions – a powerful marker of his distinct status as a person apart, not like other human beings.

There is a sense in which the Ife sculptures have also become embodiments of a whole continent, of a modern, post-colonial Africa confident in its ancient cultural traditions. Babatunde Lawal explains: