A History of the World in 100 Objects (55 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Today, many Africans, and Nigerians in particular, are proud of their past, a past that was once denigrated as being crude, primitive. Then to realize that their ancestors were not as backward as they were portrayed was a double source of joy to them. This discovery unfurled a new kind of nationalism in them, and they started walking tall, feeling proud of their past. Contemporary artists now seek inspiration from this past to energize their quest for identity in the global village that our world has become.

The discovery of the art of Ife is a textbook example of a widespread cultural and political phenomenon: that as we discover our past, so we discover ourselves – and more. To become what we want to be, we have to decide what we were. Like individuals, nations and states define and redefine themselves by revisiting their histories, and the sculptures of Ife are now markers of a distinctive national and regional identity.

The David Vases

AD

1351

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

The thrilling opening lines of Coleridge’s opium-fuelled fantasy still send a tingle down the spine. As a teenager I was mesmerized by his vision of exotic and mysterious pleasures, but I had no idea that Coleridge was in fact writing about a historical figure. Qubilai Khan was a thirteenth-century Chinese emperor. Xanadu is merely the English form of Shangdu, his imperial summer capital. Qubilai Khan was the grandson of Genghis Khan, ruler of the Mongols from 1206 and terror of the world. Wreaking havoc everywhere, Genghis Khan established the Mongol Empire – a superpower that ran from the Black Sea to the Sea of Japan and from Cambodia to the Arctic. Qubilai Khan extended the empire even further and became emperor of China.

Under the Mongol emperors, China developed one of the most enduring and successful luxury products in the history of the world – a product fit for stately pleasure-domes, but which spread in a matter of centuries from grand palaces to simple parlours all over the world: Chinese blue and white porcelain. We now think of blue and white as quintessentially Chinese, but that is not how it began. This archetypal Chinese aesthetic in fact comes from Iran. Thanks to the long Chinese habit of writing on objects, we know exactly who commissioned these two blue and white porcelain vases, which gods they were offered to, and indeed the very day on which they were dedicated.

The importance of Chinese porcelain is hard to overstate. Admired and imitated for more than a thousand years, it has influenced virtually every ceramic tradition in the world, and it has played a crucial role in cross-cultural exchanges. In Europe, blue and white porcelain is practically synonymous with China, and is always associated with the Ming Dynasty. But the David Vases, now in the British Museum, make us rethink this history, for they predate the Ming and were made under Qubilai Khan’s Mongol dynasty, known as the Yuan, which controlled all of China until the middle of the fourteenth century.

Seven hundred years ago most of Asia and a large part of Europe were reeling from the invasions of the Mongols. We all know Genghis Khan as the ultimate destroyer, and the sack of Baghdad by his son still lives in Iraqi folk memory. Genghis’s grandson Qubilai was also a great warrior, but under him Mongol rule became more settled and more ordered. As emperor of China he supported scholarship and the arts, and he encouraged the manufacture of luxury goods. Once the empire was established, a ‘Pax Mongolica’ ensued, a Mongolian Peace which, like the Pax Romana, ensured a long period of stability and prosperity. The Mongol Empire spread along the ancient Silk Road and made it safe. It was thanks to the Pax Mongolica that Marco Polo was able to travel from Italy to China in the middle of the thirteenth century and then return to tell Europe what he’d seen.

One of the startling things he had seen was porcelain; indeed, the very word ‘porcelain’ comes to us from Marco Polo’s description of his travels in Qubilai Khan’s China. The Italian

porcellana

, ‘little piglet’, is a slang word for cowry shells, which do indeed look a little like curled-up piglets. And the only thing that Marco Polo could think of to give his readers an idea of the shell-like sheen of the hard, fine ceramics that he saw in China was a cowry shell, a

porcellana

. And so we’ve called it ‘little piglets’, porcelain, ever since – that is if we’re not just calling it ‘china’. I don’t think there’s another country in the world whose name has become interchangeable with its defining export.

The David Vases are so called because they were bought by Sir Percival David, whose collection of more than 1,500 Chinese ceramics is now in a special gallery at the British Museum. We’ve put the vases right at the entrance to the gallery to make it quite clear that they are the stars of the show: David acquired them separately from two different private collections, and was able to reunite them in 1935. They’re big, just over 60 centimetres (24 inches) high and about 20 centimetres (8 inches) across at the widest, with an elegant shape, narrower at top and bottom, swelling in the centre. Apparently floating between the white porcelain body and the clear glaze on top lies the blue, made of cobalt and painted in elaborate figures and patterns with great assurance. There are leaves and flowers at the foot and neck of the vases, but the main body of each vase has a slender Chinese dragon flying around it – elongated, scaled and bearded, with piercing claws and surrounded by trailing clouds. At the neck are two handles in the shape of elephant heads. These two vases are obviously luxury porcelain productions made by artist-craftsmen delighting in their material.

Porcelain is a special ceramic fired at very high temperatures: 1200–1400 degrees Celsius. The heat vitrifies the clay so that like glass it can hold liquid, in contrast to porous earthenware, and also makes it very tough. White, hard and translucent porcelain was admired and desired everywhere, well before the creation of blue and white.

The savagery of the Mongol invasion destabilized and destroyed local pottery industries across the Middle East, especially in Iran. So, when peace returned, these became major new markets for Chinese exports. Blue and white ware had long been popular in the markets, so the porcelain the Chinese made for them mirrored the local style, and Chinese potters used the Iranian blue pigment cobalt to meet local Iranian taste. The cobalt from Iran was known in China as

huihui qing

– Muslim blue – clear evidence that the blue and white tradition is Middle Eastern and not Chinese. Professor Craig Clunas, an expert on Chinese cultural history, places this phenomenon in a wider context:

Iran and what is now Iraq are the kinds of areas where this sort of colouring comes in. This is a technique that comes from elsewhere, and therefore it tells us something about this period when China is unprecedentedly open to the rest of Asia as part of this huge empire of the Mongols, which stretches all the way from the Pacific almost to the Mediterranean. Certainly the openness to the rest of Asia is what brings about things like blue and white, and it probably had an impact on forms of literature. So from the point of view of cultural forms coming into being the Yuan period is extraordinarily important.

The David Vases are among the happy consequences of this cultural openness. Their crucial significance is that as well as their decoration, they have inscriptions – inscriptions that tell us that they were dedicated on Tuesday 13 May 1351 – a level of precision that is wonderfully Chinese and proof positive that fine-quality blue and white porcelain predates the Ming. But the inscriptions tell us much more than that. There are slight differences between the inscriptions on the two vases. This is the translation of the one on the left:

Zhang Wenjin, from Jingtang community, Dejiao village, Shuncheng township, Yushan county, Xinzhou circuit, a disciple of the Holy Gods, is pleased to offer a set comprising one incense burner and a pair of flower vases to General Hu Jingyi at the Original Palace in Xingyuan, as a prayer for the protection and blessing of the whole family and for the peace of his sons and daughters. Carefully offered on an auspicious day in the Fourth Month, Eleventh Year of the Zhizheng reign.

There’s a lot of information here. We’re told that the vases were purpose-made to be offered as donations at a temple and that the name of their donor is Zhang Wenjin, who describes himself with great solemnity as ‘a disciple of the Holy Gods’. It gives his home town, Shuncheng, in what is now Jiangxi province, a few hundred miles south-west of Shanghai. He is offering these two grand vases along with an incense burner (the three would have formed a typical set for an altar), though the incense burner has not yet been found. The specific deity receiving the offering – General Hu Jingyi, a military figure of the thirteenth century who was elevated to divine status because of his supernatural power and wisdom and his ability to foretell the future – had only recently become a god. Zhang Wenjin’s altar set is offered in exchange for this new god’s protection.

Foreign rulers, the Mongols; foreign materials, Muslim blue; and foreign markets, Iran and Iraq – all played an essential, if paradoxical, part in the creation of what to many outside China is still the most Chinese of objects, blue and white porcelain. Soon these ceramics were being exported from China in very large quantities, to Japan and south-east Asia, across the Indian Ocean to Africa, the Middle East, and beyond.

Eventually, centuries after its creation in Muslim Iran and its transformation in Mongol China, blue and white arrived in Europe and triumphed. Like all successful products, it was widely copied by local manufacturers. Willow-pattern, the style that many people think of when blue and white is mentioned, was in fact invented – or should we say pirated? – in England in the 1790s by Thomas Minton. It was an instant success, and of course it was as much a fantasy view of China as Coleridge’s poem. Coleridge may indeed even have been drinking his tea out of a Willow-pattern cup as he emerged from his opium dream of Kubla Khan’s Xanadu.

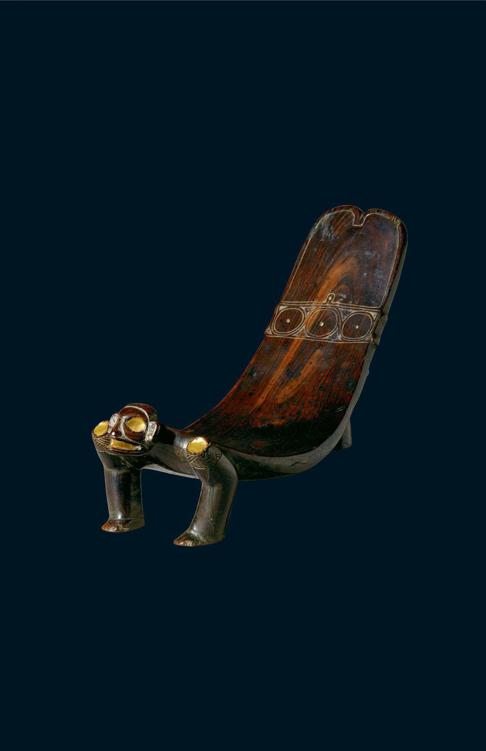

Taino Ritual Seat

AD

1200–1500

Recent chapters have described high-status objects that belonged to leaders and thinkers around the world about 700 years ago, objects reflecting the societies that produced them in Scandinavia and Nigeria, Spain and China. This object is a stool from the Caribbean, from what is now the Dominican Republic. It too tells a rich story – in this case of the Taino people, who lived in the Caribbean islands before the arrival of Christopher Columbus. In this history of the world the stool is the first object since the Clovis spear point (

Chapter 5

) in which the separate narratives of the Americas on the one hand, and Europe, Asia and Africa on the other, intersect – or, perhaps more accurately, collide. But this is no ordinary domestic thing – it is a stool of great power, a strange and exotic ceremonial seat carved into the shape of an otherworldly being, half-human, half-animal, which would take its owners travelling between worlds and which gave them the power of prophecy. We do not know if the seat helped them foretell it, but we do know that the people who made this seat had a terrible future ahead of them.

Within a century of the arrival of the Spanish in 1492 most of the Taino died of European diseases and their land was shared out among the European conquerors. It was a pattern that was repeated across the Americas, but the Taino were among the first with whom Europeans made contact, and they suffered more, perhaps, than any other Native American people. They had no writing, and so it is only thanks to a small number of objects like this stool that we can even begin to grasp how the Taino imagined their world and how they sought to control it.