A More Perfect Heaven (12 page)

Read A More Perfect Heaven Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

Rheticus had begun school with an interest in medicine but displayed an uncanny aptitude for numbers. He quickly came under the wing of the renowned humanist scholar Philip Melanchthon, “the teacher of Germany” and also Luther’s trusted supervisor of university affairs. As Rheticus later reported, the fatherly Melanchthon pushed him toward the field of mathematics—to the study of arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy. In 1536, rather than lose Rheticus after conferring on him the master of arts degree, Melanchthon established a second mathematics professorship especially for him to fill. Rheticus, now twenty-two, marked his transformation from student to faculty member at Wittenberg with a public inaugural address. Feeling awkward at the center of such attention, he warned his audience that he was

“shy by nature,”

and most dearly cherished “those arts that love hiding-places, and do not earn applause among the crowds.” Nevertheless he acquitted himself admirably in his oration. “It is characteristic of the honorable mind,” he said, “to love nothing more ardently than truth, and, inspired by this desire, to seek a genuine science of universal nature, of religions, of the movements and effects of the heavens, of the causes of change, not only of animated bodies, but also of cities and realms, of the origins of noble duties and of other such things.” Mathematics, he avowed, united all these pursuits.

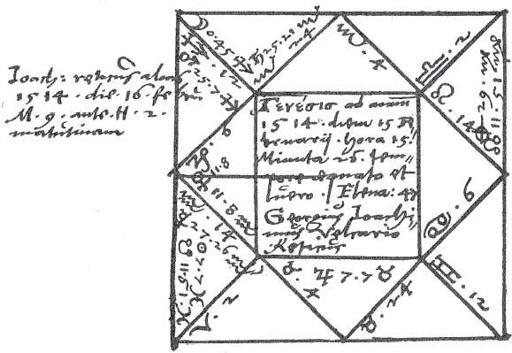

NATAL CHART FOR RHETICUS

The dire prospects suggested in this horoscope for Georg Joachim Rheticus caused his student Nicholas Gugler, who drew the chart, to recalculate the professor’s birth time and date. The true date of February 16, written in the margin, disagrees with the more favorable date in the diagram, February 15.

In addition to their mutual regard, Rheticus and Melanchthon shared a devotion to astrology that did not include the dubious Luther.

“Astrology is framed by the devil,”

scoffed Luther at table one day, “for the star-peepers presage nothing that is good out of the planets.” As espoused by Melanchthon, however, astrology contained no taint of devil or magic. Its tenets were upheld by the text of Genesis, which told how God placed “lights in the firmament of the heaven” not only “to divide the day from the night,” but also to serve as “signs.”

Rheticus had of course cast his own horoscope. His birth, in the very early hours of February 16, 1514, coincided with a conjunction of the Moon and Saturn in the twelfth house. There was no mistaking the ominous import of these conditions: They augured an abnormally short life span. As an adept astrologer, Rheticus knew several ways to rectify a bad chart. In one experiment, he technically escaped his fate by moving his birthday to the previous day, February 15, and changing the time from nine minutes before the second hour of the morning to 3:26 in the afternoon. These alterations divided Saturn from the Moon and moved them into separate houses, granting him a reprieve. But it seems unlikely that such fiddling would have rid Rheticus of the fear of impending doom. A sword, like the one that had severed his father’s head, hung menacingly over his own.

You, who wish to study great and wonderful things, who wonder about the movement of the stars, must read these theorems about triangles. Knowing these ideas will open the door to all of astronomy.

—JOHANNES MÜLLER, KNOWN AS REGIOMONTANUS (1436–1476),

AUTHOR OF THE

Epitome of Ptolemy’s Almagest

AND

On Triangles

Then spake Joshua to the Lord in the day when the Lord delivered up the Amorites before the children of Israel, and he said in the sight of Israel, Sun, stand thou still upon Gibeon; and thou, Moon, in the valley of Ajalon.

And the Sun stood still, and the Moon stayed, until the people had avenged themselves upon their enemies. Is not this written in the book of Jasher? So the Sun stood still in the midst of heaven, and hasted not to go down about a whole day.

And there was no day like that before it or after it, that the Lord hearkened unto the voice of a man: for the Lord fought for Israel.

—JOSHUA 10:12–14

And The Sun Stood Stills

A Play in Two Acts

CAST OF CHARACTERS

COPERNICUS, age 65, physician and canon (church administrator) in Varmia, northern Poland

BISHOP (of Varmia), age 53

FRANZ, age 14, the Bishop’s acolyte

RHETICUS, age 25, mathematician from Wittenberg

ANNA, age 45, house keeper to Copernicus

GIESE, age 58, Bishop of Kulm (another diocese in northern Poland) and canon of Varmia

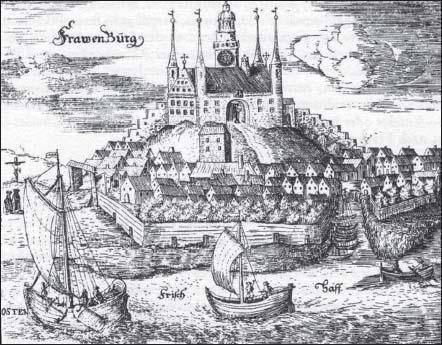

A native of Torun, Copernicus lived thirty years in Frauenburg, “the city of Our Lady,” in the shadow of its medieval cathedral. Frauenburg, the seat of the Varmia diocese, is the setting for the play.

Scene i. In the Bishop’s bedroom

House Call

The time is May 1539, in northern Poland, near a medieval cathedral ringed by fortified walls.

Darkness. The sound of someone retching. Lights up on

COPERNICUS,

standing over the

BISHOP,

his patient, who sits on the edge of the bed in his richly appointed apartment, vomiting into a basin.

FRANZ,

the frightened young acolyte, hovers and helps as needed.

BISHOP. Oh, God. Oh, Heaven help me.

COPERNICUS. I think that was the last of it, Your Reverence.

COPERNICUS

takes the basin, but the

BISHOP

grabs it and vomits one more time, then collapses back onto his bed.

BISHOP. Oh, Lord have mercy. Ohhh.

COPERNICUS. Take this away, Franz. There’s a good lad.

FRANZ

bows, exits with the basin.

The

BISHOP

writhes, groans.

BISHOP. I thought I would surely die.

COPERNICUS. The pain will subside, now that the emetic has rid your body of that toxin. You should be fine by tomorrow.

BISHOP. “Toxin”?!

COPERNICUS. It’s all gone now. You’ve expelled it.

BISHOP. Poison?!

COPERNICUS. No. No, a toxin is …

BISHOP. Lutherans!

COPERNICUS. Now, now.

BISHOP. I’ve been poisoned. If you hadn’t come, I’d be dead.

COPERNICUS. Not poison, Your Reverence. More likely something you ate.

BISHOP. Of course it was something I ate. They put it in my food. How else would they get it into me?

COPERNICUS. It could have been a bite of rotten fish.

BISHOP. The kitchen staff! That shifty-eyed cook must be a Lutheran sympathizer.

COPERNICUS. Just an ordinary bit of bad fish. Not poison.

BISHOP. The Lutherans want to assassinate me.

COPERNICUS. Or maybe too much eel. Your Reverence is extremely fond of eel.

BISHOP. I should have known better. Banishing them from the province was not enough to eliminate the threat.

COPERNICUS. Swallow this, Your Reverence. To settle your nerves and bring on sleep.

BISHOP. Sleep?! How can I sleep when Lutheran dogs are stalking me?

COPERNICUS. Sleep will be the best thing now.

BISHOP. Worse than dogs. Vermin! Evil and dangerous. They simply ignore the law. They’re below the law. Here in our midst, waiting for the moment to strike. Oh, Nicholas, what if they try it again?! Suppose they make another attempt on my life, and you don’t get here in time? What if … ?

COPERNICUS. Take this, please, Your Reverence.

The

BISHOP

refuses the medicine, pushes

COPERNICUS

away.

BISHOP. We must prosecute them more forcefully. Threaten offenders with harsher punishment. I won’t let them get me the way they got Bishop Ferber.

COPERNICUS. Bishop Ferber?

BISHOP. I see it all now.

COPERNICUS. No one poisoned Bishop Ferber.

BISHOP. They didn’t have to! He let them do as they pleased. They walked all over him. Until God Almighty intervened to smite him for not smiting them.

COPERNICUS. Bishop Ferber died of syphilis.

BISHOP. One of God’s favorite punishments.

FRANZ

returns, busies himself tidying the room.

BISHOP. Aah! It’s done now. He’s in his grave, and may he rest in peace. But why did he have to leave the whole Lutheran mess in my hands?

The

BISHOP

starts to get out of bed, but

COPERNICUS

restrains him.

BISHOP. I must deal harshly with them. I cannot afford to show weakness.

COPERNICUS

succeeds in settling the

BISHOP

in bed.

BISHOP. Oh, my heart. Franz! Bring me a glass of my Moldavian wine. And one for Doctor Copernicus.

FRANZ

exits.

BISHOP. That wine is the better tonic. To strengthen me for the fight. I’ll issue a new edict. This time I’ll ban their books, too, so they can’t … Ban them and burn them. And their music is anathema.