A More Perfect Heaven (8 page)

Read A More Perfect Heaven Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

On April 13, the chapter chose the king’s favorite, Maurycy Ferber. Bishop-elect Ferber, a distant relative of Tiedemann Giese, belonged to a politically powerful family from Danzig, where one of his kinsmen currently served as mayor of the city. Pending papal approval of Ferber, Copernicus acted as de facto bishop all through the spring and summer of 1523. He struggled to restore law and order by ridding the region of recalcitrant knights and the rear guard of the Polish military. The very forces who had come to Varmia’s defense now illegally occupied several villages and fortresses. They refused to leave until the king intervened. Following Sigismund’s orders of July 10, all Polish commanders of troops squatting in the diocese finally relinquished their claims and decamped. The knights, however, remained.

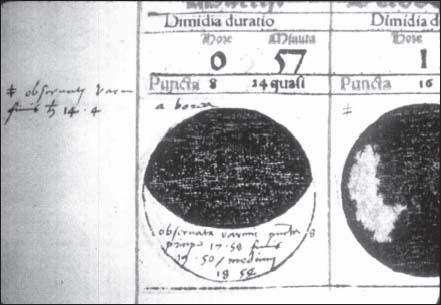

In August the Moon turned red—not as a metaphor for blood or war, but actually and naturally, as the result of a total lunar eclipse. Copernicus noted the first dip of the full Moon into the cone of the Earth’s shadow at

“2 and 4/5 hours past midnight,”

or 2:48 A.M. on August 26.

Traversing the shadow of the Earth, the Moon dimmed by degrees until fully immersed. Then, instead of disappearing in darkness, the eclipsed Moon daubed itself with the Sun’s color: It glowed like an ember throughout the hour of totality, reflecting all the dusk and dawn light that spilled into Earth’s shadow from the day before and the day ahead.

Copernicus never missed a lunar eclipse. No astronomer let such an opportunity slip, for the Moon in eclipse pinpointed celestial positions as no other phenomenon could. At such times the Earth’s shadow became visible on the Moon’s surface, and the center of that shadow indicated the location of the Sun—180° opposite in celestial longitude. With the Moon’s current coordinates thus confirmed, one could also measure the distances of stars and planets from either the Sun or the Moon.

“In this area,”

Copernicus remarked, “Nature’s kindliness has been attentive to human desires, inasmuch as the Moon’s place is determined more reliably through its eclipses than through the use of instruments, and without any suspicion of error.”

Even with the help of “Nature’s kindliness,” the tilt of the Moon’s orbit relative to the Earth’s great circle limited the frequency of lunar eclipses to once or at most twice a year, though some years have none. After August 26, there would not be another total lunar eclipse till the end of December 1525.

At the moment of mid-eclipse, which Copernicus recorded on this occasion as 4:25 A.M., the Moon stood at opposition, yet stayed its course straight ahead. Unlike Jupiter or Saturn, the Moon never shifted into reverse at opposition—or ever, at any time—because the Moon, alone among all heavenly bodies, truly did orbit the Earth.

“In expounding on the Moon’s motion,”

Copernicus wrote, with no apparent irony, “I do not disagree with the ancients’ belief that it takes place around the Earth.”

THE VALUE OF ECLIPSES

Johann Stoeffler’s

Calendarium Romanum magnum

, published in 1518, predicted eclipses for the years 1518 to 1573. Copernicus annotated his copy with his own observation notes between 1530 and 1541. The special alignment of Earth, Moon, and Sun at eclipse, called syzygy, provided a natural check on celestial positions. Copernicus witnessed both partial and total lunar eclipses, but only partial solar ones. Had he been able to travel to Spain or to the southern extreme of Italy for the April 18, 1539, event, he might have seen the Sun totally eclipsed.

Ptolemy had reported in the

Almagest

how he derived the Moon’s motion by tracking it through three eclipses of similar duration and geometry. Copernicus was following suit by observing his own three eclipses: one through the midnight hours of October 6–7, 1511; a second more recently, on September 5–6, 1522; and the third in the triad on this night, August 26, 1523. With these data, he meant to reroute the Moon.

On the path Ptolemy had charted centuries earlier, the Moon altered its distance from Earth so dramatically over the course of the month as to make it appear four times larger at its closest approach than at its most distant point. Observers never saw the Moon do anything of the kind, however. Its reliable diameter barely ever changed, yet Ptolemy and most of his followers ignored that glaring fact. Copernicus addressed the discrepancy by offering an alternate course that preserved the Moon’s appearance.

On October 13, Bishop Ferber at last assumed his rightful position, freeing Copernicus to return to Frauenburg. The chapter elections in November named him chancellor once again, but he did not expect the duties of office to impede his astronomical researches or the writing of his book any longer. At fifty, he could only guess how much time remained for those pursuits, before the inevitable loss of his stamina, or his eyesight, or the clarity of his mind.

Chapter 5

The Letter Against Werner

Faultfinding is of little use and scant profit, for it is the mark of a shameless mind to prefer the role of the censorious critic to that of the creative poet.

—FROM COPERNICUS’S

Letter Against Werner

, JUNE 3, 1524

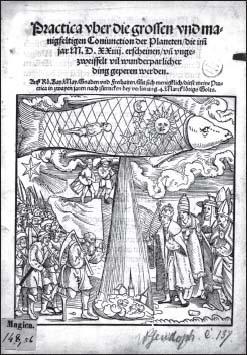

The great Conjunction of 1524 brought Jupiter and Saturn together in the sign of Pisces. Astrologers, who classified Pisces as a watery sign, predicted the dread disaster at conjunction would take the form of a mass drowning, indeed, a global inundation to rival Noah’s flood. Every Jupiter-Saturn union blew an ill wind, but this one’s evil potential drew added force from the number of other heavenly bodies convening with the main two. On February 19, Copernicus’s birthday, the planets Jupiter, Saturn, Mars, Venus, and Mercury would all cluster together with the Sun in a grand sextuple conjunction, followed by a full Moon that night. Further proof of apocalypse derived from Pisces’ rank order as the twelfth and final zodiac sign. Given that astrologers believed the world had begun under a multiplanetary conjunction in Aries, the first sign, surely it would end now under a repeat occurrence in Pisces, the last. The growth of both printing and literacy helped spread these dire prognostications so far and wide that people living in coastal regions took to the mountains. Some looked to their Bibles for instructions on how to build an ark.

February passed, and no floodwaters rose. Disbelievers scoffed at the astrologers, who held firm that waves—if not of water, then of religious dissent or political unrest—would yet wash over Europe. Had not the Great Conjunction of 1345 required two years to unleash the Black Plague?

Copernicus, who neither issued nor heeded astrological forecasts, chose this moment to pursue a bad debt. Canon Henryk Snellenberg, who had been his sole comrade in arms during the final defense of Allenstein Castle, went to Danzig and, as a favor, collected some money owed to Copernicus by his cousin on the city council there. But when Snellenberg returned to Varmia, he turned over to Copernicus only ninety of the hundred marks the astronomer’s cousin had paid. Snellenberg repeatedly put off the reimbursement of the remaining ten marks, making one excuse after another over a period of months. When Copernicus finally confronted him, Snellenberg demanded written proof of the debt, and then dared his creditor to file suit for the sum still owed. Sufficiently grieved, Copernicus complained to Bishop Ferber.

“I therefore see that I cannot act otherwise,”

he wrote to his superior on February 29, “and that my reward for affection is to be hated, and to be mocked for my complacency. I am forced to follow his advice, the advice by which he plans to frustrate me or cheat me if he can. I have recourse to your Most Reverend Lordship, whom I ask and beseech to deign to order on my behalf the withholding of the income for his benefice until he satisfies me, or a kind provision in some other way for me to be able to obtain what is mine.”

In comparison to the petulant but principled tone of his complaint against Snellenberg, the content of another letter Copernicus wrote that same year, on June 3, 1524, contained an invited analysis of such interest to the mathematics community that multiple copies of it circulated among his peers. Although terse and informal, the

Letter Against Werner

stands alongside the

Brief Sketch

and

On the Revolutions

as the third pillar of Copernicus’s oeuvre in astronomy. He addressed it

“To the Reverend Bernard Wapowski, Cantor and Canon of the Church of Krakow, and Secretary to His Majesty the King of Poland, from Nicolaus Copernicus.”

GREAT CONJUNCTION OF 1524

The combined presence of Jupiter and Saturn—along with several other celestial bodies—in the twelfth zodiac sign, Pisces (the fishes), struck dread in the hearts of astrologers, who forecast the floodwaters shown pouring from the exaggerated sky-fish in this image from Leonhard Reynmann’s

Prognostication

for 1524.

Wapowski and Copernicus had attended the Collegium Maius in Krakow together as undergraduates in the 1490s. Possibly they developed their shared interest in planetary theory at that time, perhaps even in each other’s company. Wapowski, who also went on to study law at Bologna, had later served several years in Rome with the Polish embassy, and now communicated with an international coterie of intellectuals. Copernicus alluded to the closeness of their long-standing friendship in his

Letter

’s first sentence.

“Some time ago, my dear Bernard, you sent me a little treatise on

The Motion of the Eighth Sphere

written by Johannes Werner of Nuremberg.”

Wapowski had sought Copernicus’s opinion of this widely praised paper, which was published in 1522 along with several other recent essays by the same author. Copernicus hesitated before complying, however, because he found fault with Werner’s thesis and was not at all sure he should say so. Now he excused himself to his old friend for the long delay.

“Had it been really possible for me to praise it with any degree of sincerity, I should have replied with a corresponding degree of pleasure.”

Unfortunately, the highest compliment he could offer—“I may commend the author’s zeal and effort”—took him “some time” to muster. At first, he admitted, he feared arousing anger by expressing censure in writing. Better, perhaps, to say nothing at all against Werner than risk a negative backlash that might ruin any chance of a favorable reception for his own work.

“However, I know that it is one thing to snap at a man and attack him, but another thing to set him right and redirect him when he strays, just as it is one thing to praise, and another to flatter and play the fawner.”

In the best spirit of correcting a fellow astronomer’s misstep, then, he would share his thoughts. He did not know that Werner, a clergyman at a Nuremberg infirmary, had died of the plague in 1522 while his papers were still on press.

“Perhaps my criticism may even contribute not a little to the formation of a better understanding of this subject.”

The “eighth sphere” of Werner’s title spun the stars. They were all embedded in it, like jewels in a crown. This placement accounted for the way the stars retained their fixed positions vis-à-vis one another, each in its own constellation niche, even as the heavens revolved around the Earth every day. While rolling rapidly westward, however, the eighth sphere also betrayed a slow, subtle drift in the opposite direction, which astronomers had long sought to explain. In Copernicus’s cosmos, in contrast, the eighth sphere remained stationary. It only

appeared

to move because of the Earth’s rotation. But rather than raise this fundamental difference in his critique, Copernicus focused on Werner’s technical mistakes.