A More Perfect Heaven (23 page)

Read A More Perfect Heaven Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

GIESE. I didn’t think anyone

could

ignore an idea like that.

Beat.

GIESE. But you believed him?

RHETICUS. He had no real proof.

GIESE. God rest his soul.

Beat.

GIESE. Everything is so still.

Beat.

RHETICUS. Is it?

GIESE. Hm?

RHETICUS. You know. Is it still? Or is it … ?

GIESE. What do you think?

RHETICUS. Sometimes, when I remember how he … When I hear his voice inside my head, I swear, I can almost feel it turning.

Blackout. The end.

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the Earth abideth for ever.

The Sun also ariseth, and the Sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose.

The wind … whirleth about continually, and the wind returneth again according to his circuits.

All the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full; unto the place from whence the rivers come, thither they return again.

All things are full of labor; man cannot utter it; the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.

The thing that hath been it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the Sun.

—ECCLESIASTES 1:4–9

“A generation passes away, and a generation comes, but the Earth stands forever.” Does it seem here as if Solomon wanted to argue with the astronomers? No; rather, he wanted to warn people of their own mutability, while the Earth, home of the human race, remains always the same, the motion of the Sun perpetually returns to the same place, the wind blows in a circle and returns to its starting point, rivers flow from their sources into the sea, and from the sea return to the sources, and finally, as these people perish, others are born. Life’s tale is ever the same; there is nothing new under the Sun.

You do not hear any physical dogma here. The message is a moral one, concerning something self-evident and seen by all eyes but seldom pondered. Solomon therefore urges us to ponder.

—JOHANNES KEPLER, Astronomia nova, 1609

(TRANSLATED FROM THE LATIN BY WILLIAM H. DONAHUE)

It is also clearer than sunlight that the sphere which carries the Earth is rightly called the Great Sphere. If generals have received the surname “Great” on account of successful exploits in war or conquests of peoples, surely this circle deserved to have that august name applied to it. For almost alone it makes us share in the laws of the celestial state, corrects all the errors of the motions, and restores to its rank this most beautiful part of philosophy

.

—GEORG JOACHIM RHETICUS, FROM THE

First Account

, 1540

No one knows what the brilliant, fervent young Rheticus said when he accosted the elderly, beleaguered Copernicus in Frauenburg. It is safe to assume he did not laugh at the idea of the Earth in motion. And maybe that was enough to make Copernicus open his long-shelved manuscript, and also his heart, to the visitor who became his only student. Rheticus’s enthusiasm for astronomy leapt the barriers of age, outlook, and religious difference that might well have separated the two men. As Rheticus recalled years later of their time together,

“Driven by youthful curiosity … I longed to enter as it were into the inner sanctum of the stars. Consequently, in the course of this research I sometimes became downright quarrelsome with that best and greatest of men, Copernicus. But still he would take delight in the honest desire of my mind, and with a gentle hand he continued to discipline and encourage me.”

Nor does anyone know how Rheticus’s presence in Frauenburg escaped the wrath—or even the notice—of Bishop Dantiscus. Whether Copernicus intentionally hid the youth at first, or merely concealed his full identity, he soon hustled him out of town.

As Rheticus explained the situation later in a letter to a friend,

“I had a slight illness, and, on the honorable invitation of the Most Reverend Tiedemann Giese, bishop of Kulm, I went with my teacher to Löbau and there rested from my studies for several weeks.”

Once outside Varmia, Rheticus was safe from religious persecution. The peace-loving Giese, who had long prodded Copernicus to publish his theory, must have been ecstatic to learn of their visitor’s ties to a respected printer of scientific texts. For Rheticus had brought as gifts three volumes bound in white pigskin, containing an assemblage of five important astronomy titles, three of which had been set in type and ornamented by the eminent printer Johannes Petreius of Nuremberg.

By summer’s end in 1539, Rheticus had learned enough from Copernicus to write an informed summary of his thesis. He framed this précis as a letter to another mentor, Johann Schöner, a widely respected astrologer, cartographer, and globe maker in Nuremberg—and presumably the person who referred Rheticus to Copernicus in the first place.

“To the illustrious Johann Schöner, as to his own revered father, G. Joachim Rheticus sends his greetings,”

the report began. “On May 14th I wrote you a letter from Posen in which I informed you that I had undertaken a journey to Prussia, and I promised to declare, as soon as I could, whether the actuality answered to report and to my own expectation.” He then explained how his “illness” had diverted him to Kulm for a time. After ten weeks of concentration, however, he was ready to “set forth, as briefly and clearly as I can, the opinions of my teacher on the topics which I have studied.”

Rheticus may have read a copy of the

Brief Sketch

in Schöner’s library before visiting Copernicus, or he could have come with only a vague notion of the new cosmology. Now he found himself one of two or at most three people in the world to have paged through the complete draft version of

On the Revolutions

.

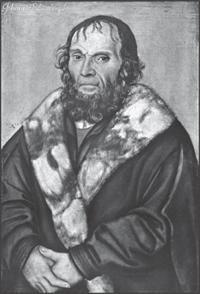

The erudite Johann Schöner of Nuremberg, as painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder.

“My teacher has written a work of six books,”

he told Schöner, “in which, in imitation of Ptolemy, he has embraced the whole of astronomy, stating and proving individual propositions mathematically and by the geometrical method.” Ticking off the topics covered in each of the six parts, Rheticus said nothing of what is today considered the work‘s most salient feature. Indeed, he remained strangely silent about the motion of the Earth until page nineteen of his protracted description. Perhaps he knew Schöner and other readers would find a moving Earth ludicrous, and so he avoided mention of it for as long as he could. Or, equally likely, he judged a different aspect of Copernicus‘s work to be more important, and therefore gave it precedence. This was the explanation of the eighth sphere, or how the daily spin of the heavens drifted slowly backward over time—the subject of Copernicus’s spar with Werner. Rheticus presented Copernicus’s numerical results without saying that the starry sphere remained stationary in the Copernican model. He concentrated instead on cyclic time patterns Copernicus had identified through observations of the Sun and stars. To Rheticus’s mind, these long cycles coincided with turning points in world history, and he seized on an interpretation that he believed Schöner would appreciate:

“We see that all kingdoms have had their beginnings when the center of the eccentric [here Rheticus refers to long-term changes in the Sun’s apparent position] was at some special point on the small circle. Thus, when the eccentricity of the Sun was at its maximum, the Roman government became a monarchy; as the eccentricity decreased, Rome too declined, as though aging, and then fell. When the eccentricity reached the boundary and quadrant of mean value, the Mohammedan faith was established; another great empire came into being and increased very rapidly, like the change in the eccentricity. A hundred years hence, when the eccentricity will be at its minimum, this empire too will complete its period. In our time it is at its pinnacle from which equally swiftly, God willing, it will fall with a mighty crash. We look forward to the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ when the center of the eccentric reaches the other boundary of mean value, for it was in that position at the creation of the world.”

Surely Rheticus had found exactly what he had come for: Copernicus’s carefully developed mathematical treatise offered a firm new footing for the most momentous predictions of astrology. Nothing could extend Rheticus’s own longevity, of course, but in his short life he believed he might yet shape a destiny, and maybe even achieve glory, by bringing Copernicus out of the shadows.

“A boundless kingdom in astronomy has God granted to my learned teacher,”

Rheticus interrupted his narrative to exclaim. “May he, as its ruler, deign to govern, guard, and increase it, to the restoration of astronomic truth. Amen.”

Next Rheticus boasted to Schöner how Copernicus had resolved the Moon’s motion without stretching or shrinking the lunar diameter. One could talk easily enough about the Moon’s going around the Earth without referring to the Earth’s motion. Only when he brought up the motions of the other planets did Rheticus finally concede that the center of the universe might shift in the new picture. And, almost in the same breath, he defended the switch:

“Indeed, there is something divine in the circumstance that a sure understanding of celestial phenomena must depend on the regular and uniform motions of the terrestrial globe alone.”

The road ahead—meaning the struggle to convince others to accept Copernicus’s wisdom—would admittedly be difficult. But Rheticus had committed himself to this course and expected Schöner to do the same.

“Hence you agree, I feel, that the results to which the observations and the evidence of heaven itself lead us again and again must be accepted, and that every difficulty must be faced and overcome with God as our guide and mathematics and tireless study as our companions.”

Even Ptolemy, Rheticus claimed, “were he permitted to return to life,” would applaud this “sound science of celestial phenomena.”

Rheticus whipped himself into a frenzy of enthusiasm as he appraised Copernicus’s labors. He found it almost inconceivable to contemplate the burden of effort that had allowed his teacher to take all the disparate phenomena of astronomy and link them

“most nobly together, as by a golden chain.”

Over the remainder of his sixty-six-page report (twice as long as the

Brief Sketch

and the

Letter Against Werner

combined), Rheticus directly addressed Schöner a dozen times, as though to shake him awake to the new reality:

“To offer you some taste of this matter, most learned Schöner,”

“Let me in passing call your attention, most learned Schöner,” “But that you may the more readily grasp all these ideas, most learned Schöner,” and so on, leading up to a final impassioned appeal:

“Most illustrious and most learned Schöner, whom I shall always revere like a father, it now remains for you to receive this work of mine, such as it is, kindly and favorably. For although I am not unaware what burden my shoulders can carry and what burden they refuse to carry, nevertheless your unparalleled and, so to say, paternal affection for me has impelled me to enter this heaven not at all fearfully and to report everything to you to the best of my ability. May Almighty and Most Merciful God, I pray, deem my venture worthy of turning out well, and may He enable me to conduct the work I have undertaken along the right road to the proposed goal.”

Other books

Summer Lovin': A Wounded Hearts Novella by Jacquie Biggar

Strange Things Done by Elle Wild

Love Among the Thorns by LaBlaque, Empress

Power of Attorney: A Novel (A Greenburg Family Book 1) by Lang, Alice

The Bachelor List by Jane Feather

Lonely Hearts by John Harvey

Down Home Carolina Christmas by Pamela Browning

Ancient DNA: Methods and Protocols by Beth Shapiro

Stink and the Midnight Zombie Walk by Megan McDonald

You're Mine Now by Koppel, Hans