A More Perfect Heaven (27 page)

Read A More Perfect Heaven Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

Some readers assumed these words to be Copernicus’s own. Others recognized them as the voice of another, but were left to guess at its identity as they continued reading.

“Therefore alongside the ancient hypotheses, which are no more probable, let us permit these new hypotheses also to become known, especially since they are admirable as well as simple and bring with them a huge treasure of very skillful observations. So far as hypotheses are concerned, let no one expect anything certain from astronomy, which cannot furnish it, lest he accept as the truth ideas conceived for another purpose, and depart from this study a greater fool than when he entered it. Farewell.”

Although Copernicus himself had at last loosed his vision of “the composition of movements of the spheres of the world,” this anonymous preamble reduced his effort to the status of an interesting and worthy aid to calculation, wholly unrelated to reality.

Anyone can rightly wonder how, from such absurd hypotheses of Copernicus, which conflict with universal agreement and reason, such an accurate calculation can be produced.

—ANONYMOUS HANDWRITTEN NOTE IN AN EARLY COPY OF

On the Revolutions

When Rheticus received his teacher’s finished book—when he realized that Osiander had won his way with it after all—he threatened to

“so maul the fellow that he would mind his own business and not dare to mutilate astronomers any more in the future.”

But he could neither prove Osiander’s complicity nor deny his own. Had he stayed at the print shop, he might have prevented this outcome. And so, with anger directed perhaps as much inward as outward, Rheticus defaced several copies of the book that came into his hands. First he crossed out part of the title with a red crayon, suggesting that “of the Heavenly Spheres” had been wrongly tacked on as an unauthorized addendum to the intended

On the Revolutions

—possibly to divert attention from the motion of the Earth. Then Rheticus put a big red

X

through the entirety of the anonymous note “To the Reader.” The crayon cross did not hide the demeaning message, however. Giese could still read it plainly in both copies of the book that Rheticus sent him, which he discovered waiting for him at Kulm, draped in the news of Copernicus’s death, when he arrived home from the marriage celebrations of Crown Prince Sigismund Augustus and Archduchess Elisabeth of Austria.

“On my return from the royal wedding in Krakow I found the two copies, which you had sent, of the recently printed treatise of our Copernicus. I had not heard about his death before I reached Prussia. I could have balanced out my grief at the loss of that very great man, our brother, by reading his book, which seemed to bring him back to life for me. However, at the very threshold I perceived the bad faith and, as you correctly label it, the treachery of that printer, and my anger all but supplanted my previous sorrow.”

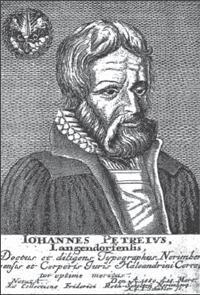

Giese could not decide whether to blame Petreius or someone who worked under him—some “jealous person” who feared that Copernicus’s book would achieve the fame it deserved, thereby forcing mathematicians to abandon their previous theories. Still, Giese insisted that Petreius bear the guilt and be punished for his crime.

“I have written to the Nuremberg Senate, indicating what I thought must be done to restore faith in the author. I am sending you the letter together with a copy of it, to enable you to decide how the affair should be managed. For I see nobody better equipped or more eager than you to take up this matter with the Senate. It was you who played the leading part in the enactment of the drama, so that now the author’s interest seems to be no greater than yours in the restoration of this work, which has been distorted.”

Giese urged Rheticus to demand the opening pages be printed anew, and to include a new introduction by Rheticus, to “cleanse the stain of chicanery.”

“I should like in the front matter also the biography of the author tastefully written by you, which I once read,” Giese said. “I believe that your narrative lacks nothing but his death on May 24. This was caused by a hemorrhage and subsequent paralysis of the right side, his memory and mental alertness having been lost long before. He saw his treatise only at his last breath on his dying day.”

Giese suggested that Rheticus also incorporate in the new introduction “your little tract, in which you entirely correctly defended the Earth’s motion from being in conflict with the Holy Scriptures. In this way you will fill the volume out to a proper size and you will also repair the injury that your teacher failed to mention you in his Preface.”

Rheticus inscribed this copy of

On the Revolutions

to Jerzy Donner, the Varmian canon who cared for Copernicus in his final days.

Copernicus’s preface, addressed as it was to Pope Paul III, could hardly have acknowledged his Lutheran assistant. But Giese had just seen himself named in the preface as the friend who overcame Copernicus’s reluctance to publish, and he must have felt sheepish receiving the lion’s share of credit for what had truly been Rheticus’s doing.

“I am not unaware,”

he reminded Rheticus, “how much he used to value your activity and eagerness in helping him. … It is no secret how much we all owe you for this zeal.” It was no secret, and yet Rheticus remained anonymous while the preface touted Giese as

“a man who loves me dearly, a close student of sacred letters as well as of all good literature,”

who “repeatedly encouraged me and, sometimes adding reproaches, urgently requested me to publish this volume and finally permit it to appear.” The preface thanked only one other person by name—the now deceased Cardinal of Capua, Nicholas Schönberg, whose laudatory, signed letter of 1536 had been exhumed from Copernicus’s files and printed in full as part of the front matter. Alas, Rheticus, who had contributed the most, was lumped of necessity with “not a few other very eminent scholars” whom Copernicus acknowledged in a single nod. Giese stumbled over himself apologizing to Rheticus:

“I explain this oversight not by his disrespect for you, but by a certain apathy and indifference (he was inattentive to everything which was nonscientific) especially when he began to grow weak.”

In closing, Giese asked whether Rheticus or anyone else had sent the book to the pope,

“for if this was not done, I would like to carry out this obligation for the deceased.”

Rheticus followed all of Giese’s instructions. As a result, the Nuremberg Senate issued a formal complaint against Petreius, but the printer pled innocence. He insisted that the front matter had been given to him exactly as it appeared, and he had not tampered with it. Petreius used such heated language in his statement of self-defense that the Senate secretary suggested his

“acerbities”

be “omitted and sweetened” before forwarding his comments to the Bishop of Kulm. The Senate, taking Petreius at his word, decided not to prosecute him. And no revised edition of

On the Revolutions

ever emerged from his press.

Johannes Petreius, citizen and printer of Nuremberg.

Several times that summer of 1543, while Giese and Rheticus sought to defend their friend’s honor, Anna Schilling returned to Varmia. Although she had moved to Danzig after Bishop Dantiscus banished her from the diocese, she still owned a house in Frauenburg. Perhaps, now that Copernicus had passed on, she expected no objection to her presence. Her visits each lasted a few days, allowing her time to remove her belongings and find a buyer. On September 9, she at last sold the property. The next day the officers of the chapter, who had been monitoring her movements all along, reported her to the bishop. They wanted to know whether she should continue to suffer exclusion from Varmia, given that the legal cause of her banishment had vanished at Copernicus’s death. It would seem she planned to leave and never return, having liquidated her last ties to the region, but still the canons posed the question, and Dantiscus rapidly replied.

“She, who has been banned from our domain, has betaken herself to you, my brothers. I am not much in favor, whatever the reasons. For it must be feared that by the methods she used to derange him, who departed from the living a short while ago, she may take hold of another one of you. … I would consider it better to keep at a great distance, rather than to let in, the contagion of such a disease. How much she has harmed our church is not unknown to you.”

From Leipzig, Rheticus sent personally inscribed, red-crayoned copies of

On the Revolutions

as gifts to his friends at Wittenberg. Their reaction to Copernicus differed markedly from the disciple’s own. Melanchthon, as intellectual leader of the faculty, followed Luther’s lead by spurning the new order of the planets on biblical grounds. One wonders whether Melanchthon ever read “the little tract” by Rheticus that Giese liked so much—the one in which Rheticus “entirely correctly defended the Earth’s motion from being in conflict with the Holy Scriptures.” If he did read it, he was not at all swayed by its arguments. At the same time, however, Melanchthon recognized the value of Copernicus’s contribution to planetary position finding, and commended Copernicus’s improved analysis of the Moon’s motion. The Wittenberg mathematicians—Rheticus’s former colleagues, Erasmus Reinhold and Caspar Peucer—echoed Melanchthon’s response. They skimmed over the heliocentric universe laid out in Book I of

On the Revolutions

, reserving their careful scrutiny for the technical sections that came afterward. They rejoiced in the way Copernicus righted Ptolemy’s wrongs by returning uniform circular motion to the heavenly bodies, but they rejected the Earth’s rotation and revolution. They ignored the reordering of the spheres, along with all the new idea’s implications for the distances to the planets and the overall size of the universe.

Reinhold immediately began constructing new tables of planetary data, based entirely on Copernicus’s devices. Although Copernicus had provided various tables in

On the Revolutions

, many of the numbers needed for calculating planetary positions lay scattered throughout the text. Reinhold gathered all this information into convenient form for working astronomers—that is, for astrologers. Melanchthon blessed Reinhold’s effort, then enlisted financial backing for its publication from Duke Albrecht, who obliged. It seemed only fitting that Reinhold name his project the

Prutenic Tables

, in honor of Prussia, home to both Copernicus and Albrecht.

No one can say what effect Rheticus might have exerted on the Wittenberg scholars had he remained among them, but it seems unlikely he could have defended Copernicus’s cosmos against the criticisms of Luther and Melanchthon. Absent Rheticus, Copernicus’s intent, which had already suffered the undermining of Osiander’s note to readers, underwent further subversions at Wittenberg. Reinhold’s published

Tables

meshed the planetary models with a stationary, central Earth. Peucer, in his book

Hypotheses astronomicae,

reinstated the ninth and tenth spheres beyond the fixed stars.

After two years at Leipzig, Rheticus, restless again, left his students without permission in the autumn of 1545 to visit the mathematician and astrologer Girolamo Cardano in Milan. Rheticus took along a gift copy of Copernicus’s book, which he inscribed to Cardano when he arrived.

The two had previously collaborated by correspondence on a collection of genitures (horoscopes) of famous men, published by Petreius in the same year as

On the Revolutions

. Now Cardano was preparing an enlarged new edition, and Rheticus gave him several detailed horoscopes for inclusion. One concerned Andreas Vesalius, the physician whose 1543 masterpiece,

On the Fabric of the Human Body

, had corrected ancient misconceptions, thereby doing for anatomy what

On the Revolutions

did for astronomy. Another geniture sketched the character and life circumstances of the mathematical prodigy Johannes Regiomontanus, who wrote the

Epitome of Ptolemy’s Almagest

—the book Copernicus had studied so closely in his youth.

Other books

The Medea Complex by Rachel Florence Roberts

Storm of Sharks by Curtis Jobling

Deep Dark Mire (An FBI Romance Thriller ~ book four) by Kelley, Morgan

Appalachian Elegy by bell hooks

Playing with Passion Theta Series Book 1 by Gayle Parness

Their Marriage Reunited by Sheena Morrish

Charles Laughton by Simon Callow

Ween's Chocolate and Cheese (33 1/3) by Shteamer, Hank

Ironic Sacrifice by Brooklyn Ann

The Beat of My Own Drum by Sheila E.