A More Perfect Heaven (30 page)

Read A More Perfect Heaven Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

“I was almost driven to madness in considering and calculating this matter,”

wrote Kepler of the Mars situation. “I could not find out why the planet would rather go on an elliptical orbit. Oh, ridiculous me!”

Unlike Copernicus, who never divulged his thought processes in print, Kepler shared with his readers many details of his progress and setbacks. He gushed in reliving for them the

“sacred frenzy”

of his ecstatic insights, and begged their commiseration for all the despair he endured.

“If you are wearied by this tedious procedure,”

he interjected in the description of his five-year “war” on Mars, “take pity on me who carried out at least seventy trials, with the loss of much time.” Sometimes he felt lost,

“hesitating in doubt of how to proceed, like a man who does not know how to put together again the dismantled wheels of a machine.”

Kepler knew who had written the unsigned foreword “To the Reader” in the opening pages of

On the Revolutions

. His own secondhand copy of the first edition had the name Andreas Osiander penned in, right above the offending note, by the book’s original owner—a Nuremberg mathematician with ties to Rheticus and Schöner. Kepler took particular umbrage at Osiander’s assertions. In 1609, when he published his

New Astronomy

calling for a science based on physical forces, he named and attacked Osiander on theverso of the title page. Now everyone would know the identity of Copernicus’s anonymous apologist.

“It is a most absurd fiction,”

Kepler railed, “that the phenomena of nature can be demonstrated by false causes. But this fiction is not in Copernicus.”

By his own self-assessment, Kepler’s pioneering achievement lay in

“the unexpected transfer of the whole of astronomy from fictitious circles to natural causes.”

Kepler demolished antiquity’s perfect circles while he was still wedded to the five regular solids as space-holders between the planetary orbits—a concept he nearly realized in silver, as a cosmic fountain for his patron the Duke of Württemberg. He never found cause to relinquish that fantastical vision of universal harmony. Nor did he ever abandon his Lutheran faith, though he felt compelled more than once to move house and change employment rather than convert to Catholicism at the insistence of local authorities. These beliefs sustained him through the difficulties of his chosen work, the deaths of his first wife and eight of his twelve children, his mother’s trial for witchcraft, and the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War.

“Thee, O Lord Creator, who by the light of nature arouse in us a longing for the light of grace,”

Kepler prayed in 1619 at the close of his book

Harmonies of the World

, “if I have been drawn into rashness by the admirable beauty of Thy works, or if I have pursued my own glory among men while engaged in a work intended for Thy glory, be merciful, be compassionate, and pardon me; and finally deign graciously to effect that these demonstrations give way to Thy glory and the salvation of souls and nowhere be an obstacle to that.”

Along with legal custody of Tycho’s data, Kepler assumed the title of imperial mathematician at the court of Rudolf II, and also the duty to compile new, improved astronomical tables in the emperor’s name. The

Rudolfine Tables

, published in 1627, indeed proved far superior to their

Prutenic

predecessors. Whereas predictions based on earlier tables might err by as much as five degrees, and sometimes misjudge an important event such as a conjunction by a day or two, the

Rudolfine Tables

honed positions to within two minutes of arc.

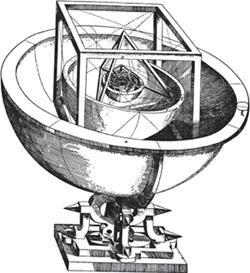

KEPLER’S VISION

While calculating conjunctions of Jupiter and Saturn, Kepler experienced a mystical vision that led him to suggest the orbits of the planets were numbered and spaced in accordance with the five regular (often called Platonic) solids. The cube that appears dominant in this image determines the interval between Jupiter and Saturn.

Although the

Rudolfine Tables

trumped the

Prutenic

, Copernicus’s original diagram of the Sun inside nested rings containing a planet apiece—the bull’s-eye icon that he drew in his manuscript and published with

On the Revolutions

—remained strangely apt. Copernicus no doubt intended the image as a mere approximation of planetary order, since he omitted more than a score of the thirty-odd circles described in his text. But now that Tycho had swept the cosmos clean of solid spheres and Kepler banished every last epicycle, the same streamlined schematic illustration rendered an actual map of the heavens.

Chapter 11

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief

Systems of the World, Ptolemaic

and Copernican

The constitution of the universe, I believe, may be set in first place among all natural things that can be known, for coming before all others in grandeur by reason of its universal content, it must also stand above them all in nobility as their rule and standard. Therefore if any men might claim extreme distinction in intellect above all mankind, Ptolemy and Copernicus were such men, whose gaze was thus raised on high and who philosophized about the constitution of the world.

—GALILEO GALILEI,

Dialogue Concerning the

Two Chief Systems of the World,

1632

In an exchange of letters in Latin between Galileo and Kepler in 1597, prompted by the publication of Kepler’s

Mysterium

, the Italian Catholic professor admitted to having long been “a secret Copernican” who could not openly espouse his belief in a moving Earth for fear of ridicule from colleagues. In reply, the German Lutheran exhorted him to join the pro-Copernican movement:

“Would it not be better to pull the rolling wagon to its destination with united effort?”

Galileo answered Kepler with silence. Not until 1610, after refining the optical instrument he called a spyglass, and discovering through its lenses heavenly marvels such as the moons of Jupiter, did he outwardly avow his support for Copernicus.

Before Galileo’s innovations refined the rudimentary spyglass, instruments had aided astronomers in defining only the positions of bodies. Galileo’s telescopes enabled observers to glimpse composition as well. The lunar landscape, for example, erupted in rocky mountains and fell into deep valleys, mirroring the surface of the Earth. The Sun exhaled dark spots that gathered and glided across its face like windblown clouds. The telescope further upset the balance of the heavens by exposing unknown bodies—not “new” entities such as Tycho’s nova of 1572 (or Kepler’s of 1604) that suddenly caught the naked eye, but never-before-seen objects beyond the reach of human vision, including ear-like appendages flanking Saturn and hundreds of faint stars filling in the outlines of the constellations. Also the planet Venus revealed a cycle of phases, from crescent to full, demonstrating beyond doubt that it revolved around the Sun. Venus’s phases fit equally well into the Tychonic system or the Copernican, but Ptolemy’s universe could not embrace such a phenomenon. Galileo published his findings.

The Starry Messenger

, a slim volume expounding his “message from the stars,” sold out within one week of its printing in Padua in March of 1610. After that, he could not build telescopes fast enough to keep pace with the demand.

Galileo’s telescopic discovery of the four largest moons of Jupiter in January 1610, described and diagrammed here in his own hand, convinced him that the Earth was not the only center of motion in the universe, and he became an outspoken “Copernican.”

News of the new discoveries spread quickly to tremendous acclaim, but Galileo also became a lightning rod for all the criticism, ridicule, and outrage that Copernicus had dreaded. Thanks in part to Galileo’s loud praise of it,

On the Revolutions

came to the suspicious attention of the Sacred Congregation of the Index, a watchdog arm of the Church created late in the sixteenth century to proscribe books that threatened faith or morals.

Copernicus had predicted trouble from “babblers who claim to be judges of astronomy although completely ignorant of the subject,” who would distort passages of Scripture to censure him. Rheticus had also anticipated such calumny, and tried to ward it off by rectifying tenets of the Copernican system with chapter and verse, with Bishop Giese’s wholehearted approval. Even Osiander, whose anonymous note “To the Reader” had so offended Giese and Kepler, probably intended to protect the book by dismissing Copernicus’s bold assertions as clever calculation devices. And, as expected,

On the Revolutions

provoked the ire of religious authorities almost from the moment it appeared.

Pope Paul III, the dedicatee, had established the Roman Holy Office of the Inquisition in 1542, a year before the book’s publication, as part of his campaign to quash the Lutheran heresy. Whether through the efforts of Rheticus or Giese, His Holiness duly received a gift copy of

On the Revolutions.

He turned it over to his personal theologian, Bartolomeo Spina of Pisa, Master of the Sacred and Apostolic Palace. Spina took sick, however, and died before he could review the book, leaving that task to his friend and fellow Dominican friar Giovanni Maria Tolosani. In an appendix to the treatise

On the Truth of Holy Scripture

, published in 1544, Tolosani denounced the deceased Copernicus as a braggart and a fool who risked straying from the faith.

“Summon men educated in all the sciences, and let them read Copernicus, Book I, on the moving Earth and the motionless starry heaven,”

Tolosani challenged. “Surely they will find that his arguments have no solidity and can be very easily refuted. For it is stupid to contradict a belief accepted by everyone over a very long time for extremely strong reasons, unless the naysayer uses more powerful and incontrovertible proofs, and completely rebuts the opposed reasoning. Copernicus does not do this at all.”

Thus panned,

On the Revolutions

eluded official denunciation for a time. All works by Rheticus, however, along with those of Martin Luther, Johann Schöner, and numerous other Protestant authors, took their places on the Roman

Index of Prohibited Books

in 1559. Petreius’s name turned up that same year on the appended list of forbidden printers, prompting some unknown number of zealots to destroy their copies of

On the Revolutions

because of its association with a prohibited press. Fortunately, the

Index

of 1564 reversed the situation by removing Petreius’s name. Two years later, when his relative Petri issued the Basel edition, a few Catholic readers obediently excised its bonus text of the

First Account

with scissors or knives. Some also deleted Rheticus’s name from that edition’s title page, by crossing it out or pasting a slip of paper over it.

In Protestant regions, where the

Index

carried no weight,

On the Revolutions

nevertheless stood open to attack on religious grounds. Kepler therefore defended the Copernican idea in the introduction to his 1609

New Astronomy

. He argued that the Holy Scriptures spoke by turns colloquially and poetically about common things such as the Sun’s apparent motion through the sky—

“concerning which it is not their purpose to instruct humanity.”

Given the Bible’s emphasis on salvation, Kepler advised readers to “regard the Holy Spirit as a divine messenger, and refrain from wantonly dragging Him into physics class.”

Other books

When Elephants Fight by Eric Walters

Penguin Lost by Kurkov, Andrey

With All My Worldly Goods by Mary Burchell

Dark Alpha's Embrace by Donna Grant

The Importance of Being Wicked by Miranda Neville

Submission Revealed by Diana Hunter

The Falling Machine by Andrew P. Mayer

Ball Peen Hammer by Lauren Rowe

Reacciona by VV.AA.