A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (27 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

Figure 7-2. Because the line in the treble clef moves away from and back to the same chord tone (E, circled), the non-chord tones (marked with X's) in the line are called neighboring tones.

Both passing tones and neighboring tones are used in Figure 7-3. But in this example they're played above a chord progression. As a result, a note that's a passing tone in one measure, such as the D in measure 3, may be a chord tone in a different measure, such as in measure 2. This example also illustrates the fact that passing tones can connect the chord tones in two different chords. In measure 1, the B and A connect the C in the C chord with the G in the G chord. In measure 2, the F connects the G in the G chord with the E in the Am chord.

Figure 7-3. Chord tones are circled and non-chord tones are marked with X's, as before. When a line is played over a chord progression, a note that's a chord tone in one measure can become a non-chord tone in another measure.

Figure 7-4. The non-chord tones in this example (the B and C, marked with X's) are played at the same time as the chord (F major on beat 1, G major on beat 3), and then resolve downward to a chord tone. These non-chord tones are called suspensions or appoggiaturas.

A couple of other types of non-chord tones are worth mentioning before we go on. The suspension, also called an appoggiatura, was introduced in Chapter Six when we talked about suspended chords. The suspension is a non-chord tone that's played at the beginning of the chord. It then moves either up or down to a neighboring chord tone, as shown in Figure 7-4.

In passing, we should note that in Baroque classical music, the term "appoggiatura" has a more specialized meaning. While it sounds and functions exactly as we've just described, it's written with a small notehead, as if it were a grace note, but with no slash-mark through the stem. Beginning around 1800, composers stopped writing appoggiaturas as if they were ornaments, but continued to use them pretty much as they had been used before. In this book, the word is used in the more modern sense.

If the suspended note never resolves by moving up or down to a chord tone, we're dealing with a suspended chord type, in which case the suspended note would be a chord tone within a different chord, not a non-chord tone. (For classical theorists, the suspension is always a non-chord tone, even if it never resolves. But this is not the case in popular music, where suspended chords are felt to stand on their own.) In the discussion in this chapter, we'll assume that the chord type is a simple triad or 7th chord, and that the suspended note resolves to a chord tone.

Figure 7-5. In the upper line in this example, chord tones are played before the beat on which the chord itself is played. Thus each of these notes starts out as a non-chord tone (for instance, the D on beat 2 of bar 1, which is a non-chord tone in relation to the C major chord). These non-chord tones are called anticipations, because they anticipate the chord that's about to be played.

In a suspension, the chord tone in the moving voice arrives after the rest of the chord. If a chord tone of a given chord is instead played early, while the previous chord is still playing, and if this note is not part of the previous chord, it's called an anticipation. The upper voice in Figure 7-5 plays a series of anticipations. Each note in this voice after the first note anticipates the following chord: The D on beat 2 of measure 1 anticipates the G major triad that arrives on beat 3, the C on beat 4 of measure 1 anticipates the F major triad that arrives in measure 2, and so on. With respect to the C chord in measure 1, the D is a non-chord tone.

Non-chord tones can be deployed in a line in other ways; the discussion in this section is not exhaustive by any means. Consider the possibilities in Figure 7-6, for instance. The point of introducing the concept of non-chord tones is to give you some ideas about how to use scales, to which we'll turn next.

Figure 7-6. Non-chord tones can be used in more elaborate ways. In measure 1 here, the upper line starts on a non-chord tone, moves past the chord tone to another non-chord tone, and finally lands on the chord tone. The B here is called an escape tone, because the melodic line starts with a D appoggiatura and then "escapes" past the expected resolution on the C before returning. In the second measure, the first non-chord tone (E) is embellished with its own neighboring tone, after which the E and C# (both non-chord tones) alternate before the D chord tone arrives.

Non-chord tones add dissonance to the harmony, and dissonance creates tension. When the non-chord tone resolves to a chord tone, the tension disappears. This fact is what makes non-chord tones so important. By deploying passing tones, neighboring tones, suspensions, and anticipations, composers create harmonic passages that are filled with emotional meaning.

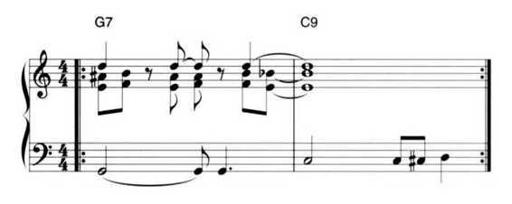

The terminology used to describe non-chord tones may seem a bit academic. I can't recall ever hearing a pop songwriter talk about using an appoggiatura or an anticipation. But such devices are used all the time. And not just in melodies. Figure 7-7 shows a funk-type rhythm comp that contains a two-note appoggiatura (the two inner notes on beat 1 of bar 1), neighboring tones (the same two inner notes, when repeated on the second beat), and an anticipation (the E and B6 at the end of bar 1, which anticipate the C9 chord in bar 2).

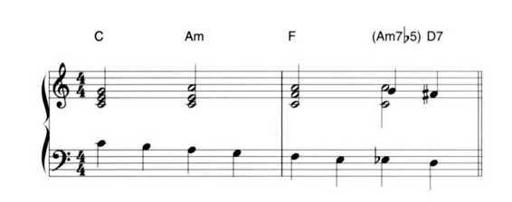

Sometimes it's a matter of personal preference whether to analyze a given note as a non-chord tone, or whether to look at it as changing the chord type. If the harmonic context provided by surrounding chords consists mostly of triads, then it would complicate matters needlessly to start talking about added 9ths and I Iths. The bass line in Figure 7-8 provides a good example of this. On beat 2 of measure 1, the B in the bass effectively turns the C major triad into a Cmaj7 chord in third inversion. Likewise, the Am triad in the second half of the bar becomes an Am7 in third inversion when the bass line moves down to G. In a folk music or country music setting, where a songwriter or arranger would rarely call for a maj7 or m7 chord type, calling the B and G passing tones makes a lot more sense.

Figure 7-7. The two inner notes on the first beat of measure 1 are suspended notes (appoggiaturas) leading into the chord tones F and B from below. The E and B6 at the end of measure 1 are anticipations, because they arrive before the C9 chord. The C# and D in the bass line at the end of measure 2, however, don't quite fit any of the designations used in the text to describe non-chord tones. If we consider the D the root of an implied D7 chord (the dominant of G), then the C# is a passing tone.

Figure 7-8. The passing tones in the bass line (B, G, and E) turn the triads into 7th chords in third inversion (Cmaj7, Am7, and Fmaj7, respectively). Most arrangers wouldn't bother inserting new chord symbols on the beats where these notes are played, however. The double appoggiatura on the D7 chord is more debatable. I wrote it this way because I liked the sound, and the underlying progression is clearly moving from F to D7, but if you'd prefer to call the chord on beat 3 of bar 2 an Am765 leading to a D7 on beat 4, 1 won't argue with you.

THE MAJOR SCALE

Now that you know a few ways to deploy non-chord tones, the question that naturally arises is, how do you know which notes to choose? While any note in the chromatic scale is fair game for a non-chord tone, most often you'll choose notes drawn from the current scale.

The major scale, which was introduced in Chapter Two, is not the only scale used in European and American music by any means, but it's the most important one. In Chapter Three, we used the notes of the major scale to build triads. The idea that most music is in a key was also introduced. The relationship between the key and the major scale is of central importance. If a piece is in the key of D major, for instance, it will use (most of the time) both chords and non-chord tones drawn from the D major scale.

The major scale (see Figure 7-9) contains a pattern of whole-steps and half-steps. Starting on the note that's the tonic of the scale, the scale contains two whole-steps followed by a half-step, and then three more whole-steps followed by another halfstep. It's this pattern - W-W-H, then W-W-W-H - that constitutes the major scale.

The white keys on the keyboard form a major scale in the key of C. When you play a major scale in a different key, you'll need to use some black keys so as to get the same pattern of whole-steps and half-steps. Almost anybody can play a C major scale (a cat walking on the keyboard can do it), but learning the patterns of white and black keys that form the other major scales may take a little effort, at least when you're new to playing the keyboard.