A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (4 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

Next, play two notes that are closer together - perhaps near the middle of the keyboard - and compare their pitches with your inner ear. The very first thing you need to learn as a musician is how to tell when one pitch is higher or lower than another. If you love music but you can't tell high from low, your only hope is to become a drummer.

This book won't contain any more drummer jokes, that's a promise. This one isn't even a good joke, because drummers routinely tune their drums to higher and lower pitches. But there's a serious point behind the joke. Most musical instruments produce tones that have clear and distinct pitches. This is true of all wind and string instruments, and it's also true of tuned percussion instruments such as piano, marimba, xylophone, and timpani. Other percussion instruments, such as drums and cymbals, produce tones whose pitch is much less distinct. A snare drum can be tuned much like a guitar string, so it makes sense to talk about a snare drum as having a high or low pitch - but because the sound of the drum is so filled with noise, it's not generally possible to say exactly what the pitch of the drum is.

We're getting a little ahead of ourselves. Pitches, you see, have names. Later in this chapter we'll explain how pitches are named. First, though, we need to explore a few other aspects of the pitch/frequency spectrum.

PLAYING IN TUNE

One of the curious facts about pitch is that while the frequency spectrum provides an infinite number of different pitches, our musical tradition uses only a relatively small, fixed set of pitches. Most of the pitches that we might play (accidentally or on purpose) fall "in the cracks" between the pitches of the conventional musical scale. We'll have very little to say in this book about those inbetween pitches. You do need to understand that they exist, however, if only so that you'll be able to judge when an instrumentalist or vocalist is playing or singing in tune.

What exactly do we mean by "in tune," and how does it differ from "out of tune"? If your instrument is the piano or some other type of keyboard, you may never need to worry about this question, because someone else will tune your instrument for you (if it needs to be tuned at all). But most musicians wrestle with tuning every day, and most instruments require that the performer be aware of the intonation of each note. "Intonation" is more or less a fancy word for "tuning," but the words are used in slightly different ways. The difference is that the instrument itself has to be tuned, while each note has to be played or sung with the correct intonation.

When two tones are sounded at the same time and have precisely the same pitch, they tend to blend together into a composite tone. This is especially true if they have similar tone colors, and if they start at about the same time. If their pitches are close but not quite the same, there will be a clash. The technical term for this clash is beating. Beating is perceived as a sort of "wah-wah-wah" effect. Beats are easiest to hear when the two tones sustain for a reasonable period of time.

The beats are actually difference tones, which are caused by the difference in frequency between the two tones. For instance, if one tone has a fundamental frequency of 440Hz while the other has a frequency of 438Hz, the difference between the two numbers is 2Hz. In this case, if the two tones are sounded simultaneously you'll hear beats at a rate of two per second. (Note: "Hz" is an abbreviation for "Hertz," which means the same thing as "cycles per second" So a tone with a frequency of 440Hz is vibrating at a rate of 440 cycles per second.)

Beats are easier to hear than to describe in words. If you have access to a guitar, by all means try listening to beats for yourself. Place a finger behind the fifth fret of the B string (the second-highest string) and play both this string and the open E string (the highest string) at the same time, allowing them to ring for a few seconds. Then retune the E string either up or down slightly using its tuning gear and play the two notes again. At a certain point, when the two notes are in tune with one another, the sound will be very smooth. If they're not tuned to the same pitch, the beats will be more or less apparent.

If you're playing an instrument that you have to tune yourself, and especially if you're playing an instrument such as violin, cello, or trombone, which has no keys, valves, or frets to help guide you to the correct pitches, learning to hear when your instrument is in tune with some reference pitch (such as the tuning note played by the oboe in an orchestra) is a vital part of musicianship. Pitch perception is also essential to hearing and identifying the two-note combinations discussed in Chapter Two.

When two tones are fairly close to one another in pitch, we can use the terms flat and sharp to describe their pitch relationship. The higher of the two tones is sharp in relation to the lower tone, while the lower tone is flat in relation to the higher tone:

sharp = higher

flat = lower

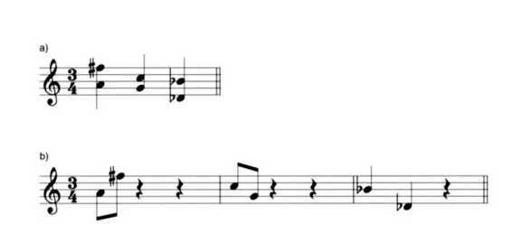

Figure 1-1. Examples of musical lines. Examples (a) and (b) are most likely melodies. Example (c) shows two independent lines notated on one staff, the top line is the melody, while the bottom line is counterpoint. Example (d) is a type of bass line. This is clear not only because it's in the bass clef, but because the pattern of notes is typical of certain old-time rock and roll styles.

We'll meet these two terms again when we start talking about scales and accidentals. They refer to half-step relationships within the scale, and also to tuning adjustments that are smaller than a half-step.

LINES, INTERVALS & CHORDS

Broadly speaking, musical sounds can be played one after another, or they can be played at the same time.

When two or more pitched sounds are played one after another, they're called a line. Melody lines (also known as melodies) and bass lines (usually the lowest notes in a piece of music) are the types of lines people usually think of first, but counterpoint lines are also extremely common. Counterpoint is a type of writing in which two or more independent lines are played or sung at the same time. For some examples of lines, see Figure 1-1. Unpitched sounds, such as drum parts, are not usually referred to as lines.

Another term that's more or less synonymous with "line" is voice. When two or more notes are played in a series, we say they're being played by the same voice. The term comes from choral writing, where a line would be sung by the soprano voice, the alto voice, or some other voice. In the sense in which we'll use the term, however, a voice doesn't have to be sung; it can be played by any pitched instrument. An instrumental voice is like a sung voice in that it is usually considered to consist of only one note at a time.

Figure 1-2. An interval always consists of exactly two tones. Here are some intervals, chosen at random. In (a), the three intervals are played together as harmonic intervals; in (b) the same intervals are played as melodic intervals, with one note following the other.

When exactly two pitched sounds are played, either one after another or simultaneously, the relationship between them is called an interval. A few random examples of intervals are shown in Figure 1-2. Intervals that consist of two notes played one after another are called melodic intervals, while those that consist of two notes played simultaneously are called harmonic intervals.

A set of three or more notes played together is called a chord. Many chords - though not all of them by any means - have names. For example, we can talk about a C major or D minor chord. Some theorists feel a group of notes played together should be considered a chord only if the notes form some sort of sensible arrangement, but I prefer to be more inclusive. As far as I'm concerned, any group of three or more notes is a chord.

A chord in which several notes are sounded at once contains one voice for each note. If the notes are all played on a keyboard or some other polyphonic instrument, saying that it consists of multiple voices may seem arbitrary: Why use the term "voice" at all, when "note" works just as well? In Chapter Eight, when we take up the subject of moving from one chord to another, the usefulness of the term "voice" will become clear.

If the notes within a chord (that is, within a chord that has a name - at this point we're using the term "chord" in a slightly narrower sense) are played one after another, the result is called a broken chord or arpeggio. The arpeggio gets its name from the Italian word for harp, because the harp - the orchestral harp, that is, not the harmonica or "mouth harp" - is often called on to play broken chords. As Figure 1-3 makes clear, a broken chord is a type of line. That is, all broken chords are lines, because they consist of pitched sounds played one after another. But not all lines consist of broken chords. If this isn't clear, it's because we haven't yet defined the word "chord" very precisely. The full definition will have to wait until Chapter Three.

Figure 1-3. Four chords. In the first two measures, the chords are played as vertical units. In the third and fourth measures, the same chords are played as arpeggios (broken chords).

Some pop musicians refer to two-note combinations played at the same time as chords. Technically, they're partial chords, not complete chords, and in this book I'll avoid using the word "chord" in this way, but you need to know that the usage is fairly common.

THE 12-NOTE CHROMATIC SCALE

The seamless rainbow of frequencies is divided up (in the European/American tradition) into a set of 90 or 100 pitches called the chromatic scale. The name "chromatic" comes from the fact that this scale contains a variety of harmonic colors. The chromatic scale contains seven or eight groups of 12 pitches each. Each group consists of the pitches A, A#/B6, B, C, C#/D6, D, D#/E6, E, F, F#/G6, G, and G#/A6. Note that five of these pitches have two names: A#, for instance, is the same pitch as B6. If you look at a keyboard, as shown in Figure 1-4, you can see why we use these names. The white keys each have a simple letter name (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) while the black keys can have either of two different names (see "Enharmonic Equivalents," below). As Figure 1-5 shows, this arrangement is repeated up and down the keyboard: Every group of 12 pitches has the same names as in the groups above and below it.