A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (19 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

On May 6 a final caravan of trucks carrying Schanberg and the last Western witnesses to KR rule left Cambodia. The evacuees peered out from behind their blindfolds on the stifling hot journey. The KR had been in charge less than three weeks, but the signs of what we would later understand to be the beginning of genocide were already apparent. All of Cambodia's major towns had already been emptied of their inhabitants. The rice paddies, too, were deserted. The charred remains of cars lay gathered in heaps. Saffron-robed monks had been put to work in the fields. Decomposed bodies lay by the side of the road, shot or beaten to death. KR soldiers could be spotted with their heads bowed for their morning "thought sessions"" The overriding impression of those who drove through a country that had bustled with life just weeks before was that the Cambodian people had disappeared.

Once the final convoy of foreigners had been safely evacuated, the departed journalists published stark front-page accounts. They acknowledged that the situation unfolding was far more dire than they had expected. In a cover story for the New York Times, Schanberg wrote: "Everyone-Cambodians and foreigners alike-looked ahead with hopeful relief to the collapse of the city.... All of us were wrong.... That view of the future of Cambodia-as a possibly flexible place even under Communism, where changes would not be extreme and ordinary folk would be left alone-turned out to be a myth."" Schanberg even quoted one unnamed Western official who had observed the merciless exodus and exclaimed, "They are crazy! This is pure and simple genocide. They will kill more people this way than if there had been hand-to-hand fighting in the city.""' That same day the Washbngton Post carried an evacuation story that cited fears of "genocide by natural selection" in which "only the strong will survive the march"''

Although Schanberg and others were clearly spooked by their chilling final experiences in Cambodia, they still did not believe that American intelligence would prove right about much. In the same article in which Schanberg admitted he had underestimated the KR's repressiveness, he noted that official U.S. predictions had been misleading. The U.S. government had said the Communists were poorly trained, Schanberg noted, but the journalists had encountered a well-disciplined, healthy, organized force. The intelli gence community had forecast the killing of "as many as 20,000 high officials and intellectuals." But Schanberg's limited exposure to the KR left him convinced that violence on that scale would not transpire. He wrote:

There have been unconfirmed reports of executions of senior military and civilian officials, and no one who witnessed the take-over doubts that top people of the old regime will he or have been punished and perhaps killed or that a large number of people will die of the hardships on the march into the countryside. But none of this will apparently bear any resemblance to the mass executions that had been predicted by Westerners."

Once the reporters had departed, the last independent sources of information dried up. Nine friendly Communist countries retained embassies in Phnom Penh, but even these personnel were restricted in movement to a street around 200 yards long and accompanied at all times by official KR "minders."" For the next three and a half years, the American public would piece together a picture of life behind the Khmer curtain from KR public statements, which were few; from Cambodian radio, which was propaganda; from refugee accounts, which were doubted; and from Western intelligence sources, which were scarce and suspect.

Official U.S. Intelligence, Unofficial Skepticism

When the KR first took power, U.S. officials eagerly disclosed much of what they knew. The Ford administration condemned violent abuses, reminding audiences that its earlier forecasts of a Khmer Rouge bloodbath were being borne out by fact. The day after the fall of Phnom Penh, Kissinger testified on Capitol Hill that the KR would "try to eliminate all potential opponents."5" In early May 1975, President Ford said he had "hard intelligence," including Cambodian radio transmissions, that eighty to ninety Cambodian officials and their spouses had been executed." He told Time magazine, "They killed the wives, too. They said the wives were just the same as their husbands. This is a horrible thing to report to you, but we are certain that our sources are accurate." Newsweek quoted a U.S. official saying "thousands have already been executed" and suggested the figure could rise to "tens of thousands of Cambodians loyal to the Lon Nol regime." With intercepts of KR communications in hand, U.S. officials were adamant about the veracity of their intelligence. "I ant not dealing in third-hand reports," one intelligence analyst told Newsweek. "I am telling you what is being said by the Cambodians themselves in their own communications"'' Syndicated columnists Jack Anderson and Les Whitten, who would regularly relay reports of atrocities over the next several years, published leaked translations of these secret KR radio transmissions in the Washington Post. "Eliminate all high-ranking military officials, government officials;' one order read. "Do this secretly. Also get provincial officers who owe the Communist Party a blood debt."Another KR unit, relaying orders from the Communist high conmiand, called for the "execution of all military officers from lieutenant to colonel, with their wives and their children."" In a press conference on May 13, Kissinger accused the KR of "atrocity of major proportions.."" President Ford again cited "very factual evidence of the bloodbath that is in the process of taking place""

But the administration had little credibility. Kissinger had bloodied Cambodia and blackened his own reputation with past U.S. policy. Just as critics heard the Ford administration's earlier predictions of bloodshed as thinly veiled pretexts for supplying the corrupt Lon Nol regime with more U.S. aid, many now assumed that American horror stories were designed to justify the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and Vietnam. Events elsewhere in Southeast Asia were only confirming the unreliability of U.S. government sources. The United States had similarly warned that the fall of Saigon would result in a slaughter, but when the city fell on April 30, 1975, the handover was far milder than expected. The American public had learned to dismiss what it deemed official rumor-mongering and anti-Communist propaganda. It would be two years before most would acknowledge that this time the bloodbath reports were true.

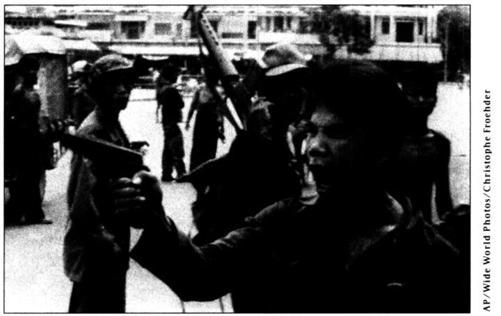

A Khmer Rouge guerrilla orders store owners to abandon their shops in Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, the day the city fell into rebel hands.

The U.S. government also lost reliable sources inside Cambodia. One of the side effects of the closing of U.S. embassies in times of crisis is that it ravages U.S. intelligence-gathering capabilities. Cambodia was especially cut off because journalists, too, were barred from visiting. Because the perpetrators of genocide are careful to deny observers access to their crime scenes, journalists must rely on the eyewitness or secondhand accounts of refugees who manage to escape. Reporters trained to authenticate their stories by visiting or confirming with multiple sources thus tend initially to shy away from publishing refugee accounts.When they do print them, they routinely add caveats and disclaimers: With almost every condemnation or citation of intelligence that appeared in the press about Cambodia in 1975 and 1976, reporters included reminders that they had only "unconfirmed reports," "inconclusive accounts," or "very fragmentary information." This caution is warranted, but as it had done during the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust, it blurred clarity and tempered conviction. It gave those inclined to look away further excuse for doing so. "We simply don't know the full story," readers said. "Until we do, we cannot sensibly draw conclusions." By waiting for the full story to emerge, however, politicians, journalists, and citizens were guaranteeing they would not get emotionally or politically involved until it was too late.

If this inaccessibility is a feature of most genocide, Cambodia was perhaps the most extreme case. The Khmer Rouge may well have run the most secretive regime of the twentieth century. They sealed the country completely. "Only through secrecy," a senior KR official said, could the KR "win victory over the enemy who cannot find out who is who.."s" When Pol Pot emerged formally as KR leader in September 1977, journalists hypothesized out loud about his identity. "Some say he is a former laborer on a French rubber plantation, ofVietnamese origin,"AFP report ed. "Others say he is actually Nuong Suon, a onetime journalist on a Communist newspaper who was arrested by Prince Norodom Sihanouk in the 1950S.1"7 When Pol Pot's photo was released by a Chinese photo news agency, analysts noted that he bore a "marked resemblance" to Saloth Sar, the former Communist Party secretary-general. The resemblance was of course not coincidental."

The KR did have a voice. They spurred on their cadres over the radio, proclaiming, "The enemy must be utterly crushed": "What is infected must be cut out"; "What is too long must be shortened and made the right length.""'The broadcasts were translated daily by the U.S. Foreign Broadcast Information Service, but they were euphemisms followed by the KR's glowing claims about the "joyous" planting of the rainy season rice crop, the end of corruption, and the countrywide campaign to repair U.S. bomb damage.

In the United States, the typical editorial neglect of a country of no pressing national concern was compounded exponentially by the "Southeast Asia fatigue" that pervaded newsrooms in the aftermath of Vietnam. The horde of American journalists who had descended on the region while U.S. troops were deployed in Vietnam dwindled. Only the three major U.S. newspapers-the New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times-retained staff correspondents in Bangkok, Thailand, and they were tasked with covering Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia (known as VLCs, or "very lost causes") as well. As soon as U.S. troops returned home, the American public's appetite for news from the region shrank. Journalists who did publish stories tended to focus on the Vietnamese boat people and the fate of American POWs and stay-behinds. Responsible for such broad patches of territory, they were slow to travel to the Thai-Cambodian border to hear secondhand tales of terror.''" Those who did make the trip found that many of the Cambodian refugees had experienced terrible suffering, hunger, and repression, but few had witnessed massacres with their own eyes. Soon after seizing the capital, the KR had hastily erected a barbed-wire harrier to prevent crossing into Aranyaprathet, Thailand, and had laid mines all along the border. The Cambodians with the gravest stories to tell were, by definition, dead or still trapped inside the country. U.S. officials estimated that only one in five who attempted to reach Thailand survived.

The dropoff in U.S. press coverage of Cambodia was dramatic. During Cambodia's civil war between 1970 and 1975, while the United States was still actively engaged in Southeast Asia, the Washington Post and New York Times had published more than 700 stories on Cambodia each year. In the single month of April 1975, when the KR approached Phnom Penh, the two papers ran a combined 272 stories on Cambodia. But in December 1975, after foreigners had left, that figure plummeted to eight stories altogether.`'' In the entire year of 1976, while the Khmer Rouge went about destroying its populace, the two papers published a combined 126 stories; in 1977 they ran 118.62 And these figures actually exaggerate the extent of American attention to the plight of Cambodians. Most of the stories in this period were short, appeared in the back of the international news section, and focused on the geopolitical ramification of Cambodia's Communist rule rather than on the suffering of Cambodians. Only two or three stories a year focused on the human rights situation under the Khmer Rouge." In July 1975 the Times ran a powerful editorial asking "what, if anything" the outside world could do "to alter the genocidal policies" and "barbarous cruelty" of the KR. The editorial argued that U.S. officials who had rightly criticized Lon Nol now had a "special obligation to speak up," as "silence certainly will not move" Pol Pot.64 But the same editorial board that called on the United States to break the silence did not itself speak again on the subject for another three years.

Cambodia received even less play on television. Between April and June 1975, when one might have expected curiosity to be high, the three major networks combined gave Cambodia just under two and a half minutes of airtime. During the entire three and a half years of KR rule, the network devoted less than sixty minutes to Cambodia, which averaged less than thirty seconds per month per network. ABC carried one human rights story about Cambodia in 1976 and did not return to the subject for two years.`

American editors and producers were simply not interested, and in the absence of photographs, video images, personal narratives that could grab readers' or viewers' attention, or public protests in the United States about the outrages, they were unlikely to become interested. Of course, the public was unlikely to become outraged if the horrors were not reported.

Plausible Deniability: "Propaganda, the Fear of Propaganda, and the Excuse of Propaganda"

Some of the guilt that Americans might have had over ignoring the terror behind KR lines was eased by a vocal group of atrocity skeptics who questioned the authenticity of refugee claims. They were skeptical for many of the usual reasons. They clung to the few public statements of senior KR officials, who consistently refuted bloodbath claims and confirmed observers' hopes that only the elite from the last regime had reason to fear. "You should not believe the refugees who came to Thailand," said Ieng Sary, deputy premier in charge of foreign affairs, in November 1975, while visiting Bangkok, "because these people have committed crimes." He urged the refugees in Thailand to return to Cambodia, where they would be welcomed."" In September 1977 Pol Pot said in Phnom Penh that "only the smallest possible number" out of the " 1 or 2 percent" of Cambodians who opposed the revolution had been "eradicated." Conceding some killings gave the KR a greater credibility than if they had denied atrocities outright, and many observers were taken in by these concessions.''-