A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History (25 page)

Read A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History Online

Authors: Peter G. Tsouras

Tags: #(¯`'•.¸//(*_*)\\¸.•'´¯)

Baker went on, "It's actually the easiest duty in Washington. Just

sit outside his office or follow him around and keep the office seekers

off him. And there's some free entertainment. He likes to go to the theater a lot."

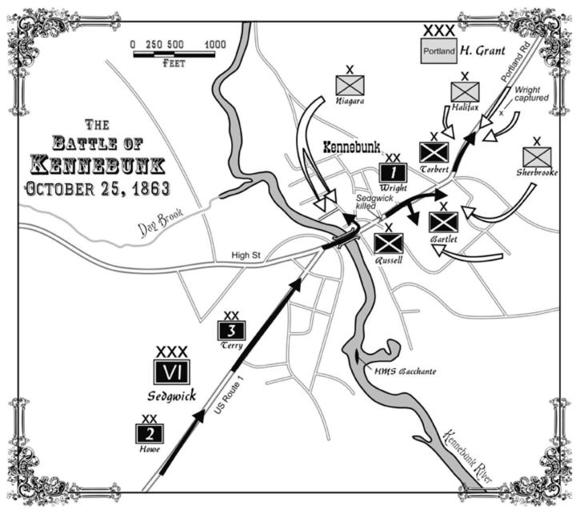

KENNEBUNK, MAINE, 10:18 AM, OCTOBER 25, 1863

As soon as Hope Grant caught up with the British Portland Force marching south to meet the American VI Corps, the column picked up its pace.

As commander of all of Her Majesty's forces in British North America,

he immediately assumed command. As an old cavalryman, he knew the

value of speed. In this he was much like the late Stonewall Jackson. He

pushed his Imperial and Canadian battalions down the Portland Road.

Scouts reported the advance of the Americans coming north also on the

Portland Road. John Sedgwick knew how to hard-march his men as well

as Grant. The forced march of the VI Corps to Gettysburg on July 2 had

been an achievement by any standard. They numbered fifteen thousand

men and forty-two guns. They were tough as nails.'

Grant's study of the map pointed to the little town of Kennehunk,

bisected by its eponymous river, as the likely point where the two columns would meet. The river was crossed by Durrell's Bridge, which connected the two halves of the town, and seven shipyards clustered down

both banks. Kennehunk was a major shipbuilding center, and building

materials lined the streets and roads leading to the river. Doyle could

tell him little of the enemy that he faced other than its high reputation

as a fighting formation and its commander as a fighting general. Almost

immediately, Grant sent a courier off to the coast to make contact with

whatever Royal Navy ships were blockading Kennehunk at Kennehunk-

port, a few miles downriver.

For Sedgwick's part, he had no idea that he was about to meet the

foremost British general of the age. His last information had Doyle still

at Portland. Grant had had the foresight to cut the telegraph and race

ahead of any warning. The Brunswick Regiment of Yeomanry Cavalry

was effectively screening his advance -until they were hit hard by the

small cavalry brigade attached to Segdwick's corps. At the first sound of

gunfire to his front, Grant deployed his battalions and moved forward.

It was not long before the Canadian cavalry came flying past. The Union

cavalry were close behind, but the closely wooded road had masked the red lines from them until the last moment. A volley from the 17th Foot

brought down the head of the column in a tangle of bodies and screaming, flailing horses. Grant ordered them forward, and the red ranks

surged ahead, bayonets at the level.

Sedgwick's first knowledge of the British was when some of his cavalry came tearing back through Kennehunk to tell him that they had run

into redcoats only a few miles north. No one ever accused Uncle John

of being a Napoleon, but he was steady and unflappable, attributed by

some to an utter lack of imagination. But he knew what to do in a fight.

His first division was approaching the bridge over the Kennehunk River.

The others were strung out for miles to the south. He sent couriers after

them to hurry the pace.

The first men over the bridge would be Horatio G. Wright's 1st

Division. Sedgwick wanted his best to land the first punch. Wright had

only recently been given division command after a brilliant record in

the West. The man was slated for a corps command one day, and Meade

had been eager to find him a division. Meade had other reasons. Wright

would be senior to the 2nd Division commander, Brig. Gen. Albion P.

Howe, who had the great talent of alienating just about everyone above

him in the chain of command. Howe and Sedgwick simply did not get

along. Howe was also a partisan of Hooker's, whom Meade has succeeded, and then a partisan of Sickles in the controversies surrounding

Gettysburg, going so far as to testify against Meade before the House's

witch-hunting Committee on the Conduct of the War. It was inevitable

that Howe would come to be called "Perfidious Albion."

PORT HUDSON, LOUISIANA, 12:33 PM, OCTOBER 25, 1863

It had been the retreat through a green hell. The exhausted survivors of

Franklin's XIX Corps struggled into the defenses of Port Hudson as the

black faces of the Corps d'Afrique looked on their shambling ranks with

wide eyes. It had only been a fifty-mile march, but miles down roads that

were barely tracks through the great stinking expanse of swamp, marsh,

and bayou. One by one its wagons and guns had been abandoned and at

last even its ambulances full of groaning misery. The wounded had been

mounted on the horses or carried in litters.

On the road north from Vermillionville to Opelousas, Franklin had

gone northeast to Leonville to cross Bayou Teche, then back south to Araudville and from there the great "muck march," as the men would

call it, to the Bayou Grosse Pointe and across. It was there that Franklin

heard the news of the fall of New Orleans and the imminent fall of Baton

Rouge. That dashed his hopes of taking the railroad from Rosedale to

West Baton Rouge. He would have to take his worn-out men another

fifteen miles north through more hellish swamp country to safety in

the fortifications of Port Hudson. Along with Vicksburg, Port Hudson

had been one of the two strong fortresses keeping the Mississippi out of

Union hands. It had fallen four days after Vicksburg. Now he realized it

would have to serve the Union, hopefully better than it had served the

Confederacy.

Franklin was thankful to find the river below Port Hudson filled

by the U.S. Navy. A good part of the river squadrons that had fought

so hard to free the Mississippi were there. The sailors was glad of the

chance to do something useful in the midst of catastrophe and ferry

Franklin's men over to Port Hudson. It was a nervous post commander,

Brig. Gen. George A. Andrews, who met Franklin at the landing. All

he could talk about was how the French army and fleet were about to

march upriver and overrun the fort. Franklin smelled the man's panic

and pulled him by the arm over to a quiet place. "General, this fort will

hold, by God. This fort will hold. And you are going to help me do it."

All Andrews seemed to need was someone to take charge, and Franklin had done just that. "First thing, I need to get my men fed and the

wounded to hospital." Andrews's panic had not let him neglect the military administration he was very good at.

"I've already given orders, sir. Every cook at this post is slaving

away, and more tents are going up at the hospital. We've already been

overrun by refugees up from New Orleans, so we were doing a lot of this

anyway. The Navy's brought thousands to here and Baton Rouge."

"What is the strength of the garrison?"

"Besides four artillery batteries and a cavalry regiment, I have a brigade of infantry of the Corps d'Afrique-about three and half thousand

men in all."

"I have one of my own brigades at Baton Rouge, "said Franklin,

"but the place can't be held against a superior force. The last I saw of

Banks, he was with XIII Corps as it was being crushed by the French. Do

you have any word from him?

"Nothing, General."

"Then who is in command of the Department of the Gulf?"

"Why, I expect you are, sir."

KENNEBUNK, MAINE, 1:29 PM, OCTOBER 25, 1863

Big white flakes were falling in the first snow of the season as the

command group galloped along Main Street north of the bridge. The

sound of gunfire up ahead seemed muffled by the falling white blanket

when a shell burst overhead in an orange spasm that spewed black iron

fragments. Sedgwick rose up from the saddle and then toppled over to

the ground without a sound. His staff rushed to him, but the gaping hole

in his forehead told them there was nothing to be done. He had been riding beside a regiment pushing forward to the fight and was waving them

on with his hat. They had seen him go down and groaned as one man. VI

Corps loved "Uncle John" and would not take this kindly.'

The 1st Division had barely passed over the bridge when the British hit the head of the column on the edge of town. Hope Grant's map

reconnaissance told him the bridge was key terrain feature, a choke point

that delayed passage of large bodies of men and vehicles. If he could

catch part of the enemy's force on the near side and smash it, then the

remainder would retreat. He did not need to destroy the enemy, just

keep them from relieving Portland. Without Portland, Canada could not

be held.

His timing had been flawless. He had driven back the enemy cavalry and then marched so quickly that he was able to catch the Americans before they were even halfway across the bridge and still in column.

That had been the easy part. Speed, surprise, and the grit to slug it out

toe to toe had been the secret of his success against Sepoy and Chinaman. Against the Americans it might not he enough.

Speed had brought Grant's red battalions sweeping up to Kennehunk. The British hreechloading Armstrong guns were very accurate

at a long distance, and their first volley killed Sedgwick and burst over

the stone spans of Durrell's Bridge, which was packed with men of the

49th Pennsylvania and the guns of the Battery F, 5th U.S. Artillery. The

bridge exploded into a bloody shamble, clogged with dead and wounded men and horses, and guns, caissons, and limbers overturned by their

dying and wounded animals.

Wright now found himself on the north side of the river with only

two brigades. His last brigade and the other two divisions were stacked

up on High Street on the other side of the river as men desperately tired

to clear the bridge. Wright was ignorant of both Sedgwick's death and

the severing of the corps column because he was urging on Brig. Gen.

Alfred T. A. Torbert's New Jersey Brigade in the lead. He knew the enemy was ahead from the reports of the cavalry and was determined to get

his division out of town and deployed. Grant had the opposite purpose.

The last thing he wanted was for the Americans to deploy outside the

town; then they would be able to feed their entire force into the fight and

have numbers on their side. No, he must hit them in the town and force

them back to the bridge. It was a race, pure and simple.

That was why Wright rode past the 1st New Jersey, his lead regiment, to personally reconnoiter the ground ahead for the battle. Behind

him rode his escort, a hundred men of the 1st Vermont Cavalry. Almost

as soon as they turned off Main Street to the Portland Road, they ran

into the Canadian 54th Sherbrooke Battalion blocking the road. Their

volley ripped into the head of the cavalry column, tumbling men and

horses in a kicking, screaming knot on the road. As the survivors turned

back, skirmishers went forward to round up prisoners. Pinned under his

horse, Wright found himself looking up into the blued point of a Canadian bayonet. Beyond the honor of capturing a general officer, the Sherbrooke men had done a great service to Grant. They had decapitated VI

Corps. With Sedgwick dead and Wright captured, command would have

devolved on Albion Howe, had he known of the fate of the other two.

But he was still south of the bridge with his division. VI Corps would

fight that day without a commander.'

Sweeping in from the south, the 17th (Leicestershire) Foot, almost a

thousand men strong, struck Wright's lead regiment, the 1st New Jersey,

just as it exited the town. The British were known as the Bengal Tigers

from their service in India, and an apt nickname it was. Their volley

shattered the far smaller New Jersey regiment, and their bayonet charge

finished them off. They pushed down Main Street to collide with the

next regiment, the 4th New Jersey, which stubbornly blocked the road.

Two more Canadian militia battalions came up to feel the flanks.

Grant himself led the 63rd (West Suffolk) Regiment of Foot known

as the Blood Suckers, with its three Canadian militia battalions of the

Niagara Brigade to attack into the town from the west. They drove

straight to the bridge to run into Wright's third brigade, which had

just cleared the wreckage and was beginning to stream across. The

5th Wisconsin double-timed off the bridge to wheel into line to face the

Niagaras.

Wisconsin regiments were particularly tough. Wisconsin was the

only state to keep its original regiments up to strength rather than raise

new regiments as the old ones shrank due to casualties and illness.

Regiments were kept strong, and the fighting skills and spirit of the old

hands was passed to the new men. Now, seven hundred Wisconsin men,

flanked by battery of the Rhode Island Light Artillery, leveled their rifles and fired into the red-coated column coming down Stover Street. The six

guns followed in ten seconds to catch the men in the back of the column.

The 58th Compton Battalion disintegrated from the blows. The Wisconsin men pushed up the street in pursuit where they ran into the Blood

Suckers coming their way. Both columns fired at the same time. The 5th

Wisconsin's colonel and lieutenant colonel both went down, as did the

commander of the 63rd. Now it was a soldier's fight as the men spread

out among the houses and yards. A company was too big to control as

the fighting went house to house. It was close-quarters work with pistol,

rifle butt, and bayonet as groups of men broke into a house or fired from

its windows, and rushed across small yards. The 119th Pennsylvania

fed into the fight just as more Canadian militia were flanking through

the alleys.10