A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History (27 page)

Read A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril an Alternate History Online

Authors: Peter G. Tsouras

Tags: #(¯`'•.¸//(*_*)\\¸.•'´¯)

Welles faced down Stanton, who insisted that Lincoln evacuate the

capital before Lee and the British arrived. "Stanton, I told you last year when you were in a panic that the Rebel ironclad Virginia was about

to ascend the river and subdue the entire capital that it drew too much

water to get past Kettle Bottom Shoals. And that's fifty miles down the

river. If Virginia couldn't make it with twenty-three feet of draft, how do

you expect those British monsters with twenty-six feet of draft to do it?"5

Stanton was literally wringing his hands, "But the British got up the

river in 1814!"

Welles snorted in contempt. "Yes, and it took them twenty days to

get through Kettle Bottom because they kept grounding on the shoals,

and they have bigger ships today. I guarantee you will not see Warrior

coming up the river. If any of their ships get through, it will he their

smaller ships. We still have the river forts and gunboats and plenty of

guns at the Navy Yard."

"But. .."

"Stanton, let me worry about the Navy. I would think you have as

much as you can handle with Lee."

A clerk ran in and handed Lincoln a telegram. He raised his hand,

"I have a telegram from Sharpe." The room went silent. "Lee himself is

on his way up from Mount Vernon; Sharpe expects the rebels to be in

front of the forts within an hour. Let us pray the forts hold until Meade

arrives."

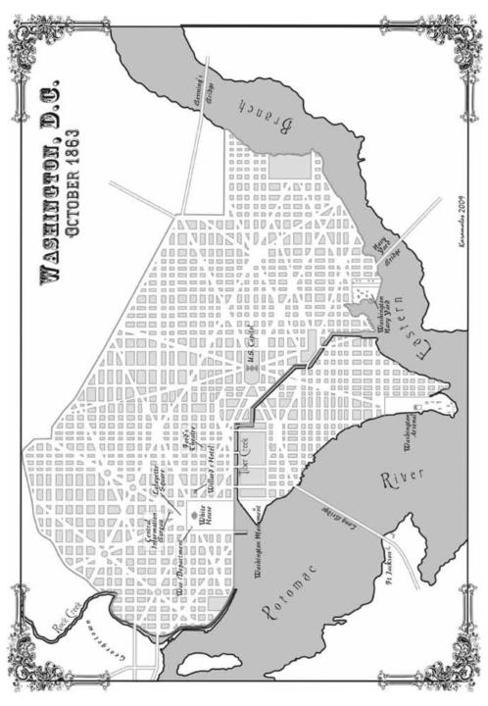

Lincoln had good reason for his confidence in the dense ring of fortifications around the capital. Since his arrival in Washington,

... from a few isolated works covering bridges or commanding a

few especially important points, was developed a connected system of fortification by which every prominent point, at intervals

of 800 to 1,000 yards, was occupied by an inclosed [sic] field-fort,

every important approach or depress of ground, unseen from the

forts, swept by a battery of field-guns, and the whole connected

by rifle-trenches which were in fact lines of infantry parapet, furnishing emplacement for two ranks of men and affording covered

communication along the line, while roads were opened wherever

necessary, so that troops and artillery could he moved rapidly

form one point of the immense periphery to another, or under cover, from point to point along the line.'

These defenses had much to defend besides the seat of government.

Although Alexandria served as a major subsidiary depot for supplies,

Washington itself was the Union's primary and largest logistics center.

As one observer noted:

Hardly had war begun when camps, warehouses, depots, immense stacks of ammunition, food, equipment and long rows of

cannon, caissons, wagons and ambulances began sprouting up

all over town in vacant lots and open spaces. Centers of activity included the Navy Yard, the Army Arsenal and the Potomac

wharves at Sixth and Seventh Streets SW. By 1863 another huh of

activity had grown along the Maryland Avenue railroad yards.

These busy centers lined the southern rim of the city fronting on

the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers.'

Ships unloaded off the Potomac along the Arsenal wharves and

off the Eastern Branch south of the Navy Yard where the channel was

deepest.'

The area of Foggy Bottom saw the concentration of a mass of supplies, equipment and material, and storehouses. There was also a remount depot for approximately thirty thousand horses and mules. The

large open area near the unfinished Washington Monument was a huge

slaughtering yard for cattle. Near the Capitol, another collection of supply warehouses and yards grew up along Tiber Creek near the Baltimore

and Ohio Railroad depot and repair yards. More facilities of every kind

were scattered throughout the rest of the city.' Originally named Goose

Creek, this tributary of the Potomac had been given its grander title in

hopeful emulation of la cittd eterna. It had later been converted into the

Washington Canal, which was crossed at intervals by high iron bridges.

It failed in its purpose as a major thoroughfare and degenerated into an

open sewer that emptied into the Potomac just south of the Presidential

Park, which led north to the White House.

The Washington Arsenal was the largest of the government's

twenty-eight arsenals and armories and specialized in the assembly and

storage of munitions and the storage of artillery. Its complex of buildings - foundries, workshops, laboratories, and magazines - occupied the southern tip of the city where the Potomac and Eastern Branch Rivers

met. It had a large workforce, including over one hundred women and

two hundred boys whose fine motor skills were preferred for the delicate

tasks of assembling the munitions, which ranged from rifle cartridges to

artillery shells.

Outside its gates lay a number of captured bronze guns from the

victories of Saratoga, Yorktown, Niagara, and Vera Cruz. When the

British marched on Washington in 1814, Arsenal workers had hidden

gunpowder down a well. A large party of British soldiers swarmed over

the site, and one carelessly threw a lighted match down the well onto the

gunpowder bags, destroying every building in the Arsenal.1°

The Navy Yard in southeast Washington lay along the Eastern

Branch to the uppermost point of navigation. Directly above it was an

old, rickety, wooden bridge that connected Washington to Maryland.

The Navy Yard was the premier of the Navy's great yards, and its vast

foundries and dry docks were a major production center for Dahlgren

guns and the more complicated mechanical devices of war. It was there

that Lowe's gas-generating equipment was fabricated by the teams of

skilled mechanics and artisans and where those same teams had built the

experimental Alligator-class submarines that Dahlgren had used so well

at Charleston. The Yard's facilities were so complete that entire ships

could be built, repaired, or converted from merchant to naval service

there as Gettysburg had been. The Navy Yard was a major military objective in itself.

When the war began, Washington's population had been about seventy-five thousand; in the subsequent two and a half years, it had almost

doubled and had provoked a vast spate of building. Nevertheless, a view

of the city's street plan would still have been misleading. The neat grid

did not reflect reality. Much of the land of the city was still uninhabited.

That was especially true of the large section south of Tiber Creek, which

was called "The Island" because it was bound largely by the creek and

the Potomac. Its most important and only civic building was the Gothic

Smithsonian Institution. Along the ends of 6th Street and 7th Street, SW,

were the wharves and docks for the river and sea traffic that connected

the city to Alexandria, Aquia Creek, the Chesapeake Bay, and finally

the sea " The Island also contained the most important military installa- Lion in the District of Columbia- the Washington Arsenal. Just outside

the southeastern outlet of the canal into the Eastern Branch was the

Washington Navy Yard. Outside each installation, small communities

had grown up to house their employees and the military personnel assigned to them. The Marine Barracks were only a block beyond the Navy

Yard. The country between these installations and the rest of the city was

largely uninhabited. An omnibus to the rest of the city connected the

Yard.l" Thus two of the country's most important military installations

were self-contained and not physically part of the city. They were also on

the southern and southeastern edge of the city and most easily accessible

to an attack up the Potomac.

The most densely built-up part of the city ran east and north of the

canal. Across the canal and along 10th Street, NW, was Hooker's Division. The canal emptied into the Potomac where the forlorn stub of the

incomplete Washington Monument stood almost on the water's edge.

Running just inland from the monument was the major thoroughfare

of 14th Street, which connected to the immense wooden Long Bridge

that spanned the Potomac. Earlier that year, the Army had constructed

a railroad bridge to parallel the Long Bridge. A few houses and a hotel

clustered around the bridge entrance. Small guardposts at either end of

the bridge checked all traffic.13

The fall of Washington now would not only paralyze the national

government, but would also disorder the logistics of the war effort and

bring it to a halt. "These depots, the arsenal, the large Quartermaster and

Subsistence depots in the city, and the branch Quartermaster depot in

Alexandria served the country, the nearby armies, and the army activities in and near the city."14

As the Cabinet officers left the White House, Stanton noticed the

military guard around the building was much heavier than the small

detachment that had been there before. He accosted the officer of the

guard and demanded to know who had assigned these men. His jaw

set when told it was the 120th New York Volunteers. Stanton turned his

formidable personality on the young man. "And who ordered you here,

Captain?"

"General Sharpe did, Mr. Secretary."

The first thing Stanton did on his return to his office was to call in

Lafayette Baker. Stanton paced back and forth in front of his fireplace. "Baker, I want you to increase the number of detectives you have protecting the president."

Baker had been fully aware of how Sharpe's New Yorkers had taken

over security of the White House. That was getting too close to Baker's

responsibility to protect the president himself. It did not take a genius to

know that someone was crowding his territory, in more ways than one.

He had already identified Sharpe as a rival and therefore an enemy, especially after he became aware of inquiries that seemed to point back at

Sharpe about Baker's own extrajudicial methods that poured money into

his pockets.

Baker was quick off the mark. Stanton had offered him an opportunity to reassert his power, and he snatched at it. "Yes, Mr. Secretary.

I have already seen to it two days ago. The new man's done excellent

work already. Comes from Indiana with the highest recommendations as

a bodyguard."

"Keep an eye on this, Baker. Take nothing for granted." 15

THE DOCKS, 7TH STREET, SW, WASHINGTON, D.C.,

5:22 AM, OCTOBER 26, 1863

Booth reveled in the melodrama of their meeting. For him, the passions

of the stage were indistinguishable from those of life and death. Now,

under the gas lamplight on the river docks with the mist rising off the

river from the kiss of the cold fall air on the water, he was in his element.

He waved his silver-headed cane as if it were a sword. Smoke, for his

part, did not suffer from such flights of imagination; it was not a survival

trait in his line of work. Booth was a tool in his larger plan, a tiresome

tool that required more tact to handle than Smoke liked to expend, but

he was all he had to work with. If he had thought to look back on the

efforts to reel Booth into the plan and keep him on it, he would have

marveled at how he had risen to the occasion. But Smoke was not a man

for reflection; he was a man to follow orders, the subject of their meeting

under the gaslight.

"Our chances are good," Smoke said. "Lincoln regularly walks to

the War Department or to Sharpe's office to see the telegraph traffic. The

way our friends have been stirring things up, he's back and forth all day.

I'm the only one with him. We just have to be waiting for him. Just as we

planned."

Booth stabbed the metal tip of his cane at the cobbles. "Excellent.

Almost as predictable as an entry stage right." This time he flourished

the cane as if were a wand. "His exit will be more in the way of a magician's disappearing act."

"Damn it, Booth. What have I told you? No play-acting. We do it

fast and quiet. The last thing we need is an audience."

Booth came down from his high quickly, "Of course, of course. Just

as we planned."

Then Smoke took Booth by the upper arms and looked intently at

him. "This morning, Booth. This morning. It has to be this morning. The

wagon is waiting."

Booth seemed to shrink away at first. All the fine and heroic talk of

kidnapping the president had played to his vanity. He had shown an unexpected attention to the details of the act and had coolly played his part

in their brief rehearsals. But now was the moment when he had to fix his

courage to the sticking point. The whole thing hung in the mist.

Then, as if leaping onto the stage from a height, Booth took a step

forward and grasped Smoke's hand. He cast his perfect pitch voice to

carry just in the space between them, "Sic semper tyrannis!"16

HEADQUARTERS, CENTRAL INFORMATION BUREAU (CIB), LAFAYETTE

SQUARE, WASHINGTON, D.C., 6:30 AM, OCTOBER 26, 1863

Much of the infantry garrison of Washington had already been stripped

to reinforce Hooker and Sedgwick in the north, leaving mostly the heavy

artillery regiments that manned the forts. Every fort and redoubt was

on full alert and was tied to Sharpe's intelligence operation by telegraph,

signal station, or messenger. The balloons went up again in the morning

to the relief of the artillerymen who looked on them almost as if they

were guardian angels. Their officers knew full well what the eyes in the

sky could do for them. They would need every advantage now that the

infantry regiments that had manned the miles of trenches and works

between the forts were largely gone. They were lucky if there was one

rifleman to twenty feet of trench line-not enough to stop a determined

charge.