A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (39 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

He extricated himself and finding himself alone on the slope he started digging frantically, looking for the others. As he neared Yeshe the snow was red and as he cleared her face of snow so she could breathe, he saw blood spurting from a huge gash across the top of her head. When he laid her on the surface of the snow, she was barely breathing and she was unconscious.

Thrashing the snow like a dog, his hands bent like claws, the Lachung Lama dug. He didn’t stop until he found Lama Tashi who was bleeding from a gash above his eye, his left hand bent at right angles to the arm. He was in so much pain that he was in shock and barely conscious.

A loose page of one of the

pechas

that had been strapped to Tulshuk Lingpa’s back appeared out of the dense fog and slapped the Lachung Lama on the face in a great gust of wind. Following where it came from with his eyes, he saw more pages. They had been mixed with snow by the avalanche and were waving in the wind. He leapt down the loose slope and clawed at the snow. It was by following the density of pages that he found Tulshuk Lingpa.

Tulshuk Lingpa’s body showed no external mark of the accident. As the Lachung Lama dug him out, Tulshuk Lingpa’s legs were crossed. He was slumped over, his eyes closed and frosted with snow—and he was dead.

Uncovering but not moving the body, shocked by the magnitude of his discovery, he fell back in the soft snow and stared at the leaves of the

pechas

. They were blowing in the foggy gusts of wind, sliding by on the snow and disappearing into the steep grey distance.

The Lachung Lama ran down the slope to get help. He went to where the others were waiting and gave them the news. Then together they went up to care for the living and offer homage to the dead.

At first they couldn’t tell if Yeshe was dead or alive. The young woman, who had seen the vision of Beyul green and replete with waterfalls only that morning, lay on the snow at the edge of death. The snow beneath her head was red with blood. They wrapped her head in an effort to stop the bleeding. Then, stripping Tulshuk Lingpa of his heavy sheepskin coat, they rolled her in it.

Taking off their own coats, they wrapped Lama Tashi in them. They wrapped the two in whatever hats and scarves they had to keep them warm through the night, for evening was falling and both were hovering too close to the edge of death to be brought immediately down the mountain.

So they left the three of them there, the two living keeping half unconscious night vigil over their dead guide. Lama Tashi slipped in and out of consciousness all night. He thought the two motionless bodies beside him were dead and that for sure he was dying.

He awoke to the rays of the sun striking him from behind a distant peak. Shock soon gave way to pain. His arm was badly broken and his fractured ribs pained with every breath. The continual loss of blood kept him on the edge of consciousness while the shock of the avalanche kept him from remembering what had happened. He didn’t know why he was lying on that snow slope with his lama lying dead on one side and Yeshe hovering near death on the other.

When the sun was slightly higher in the sky and their companions reached them, Yeshe was in far worse shape than Lama Tashi. She had bled badly all night and they could hardly bring her to consciousness. They gave Lama Tashi something to eat, hoisted the three of them on their backs and carried them down to the cave to rest. Then they headed down the mountain. That night they slept where they had stopped for the night when they were coming up. The next day they reached Tseram.

The hundreds of people camped at Tseram hadn’t heard any news of the expedition since they left three weeks earlier. In a heightened state of excitement, they were awaiting word that the way was open, speculating on whether any of them had had the patience to postpone their entering to tell the others back in Yoksum and at Tashiding.

The sight of the column of climbers wearily descending to Tseram, three of them being carried on others’ backs, was enough to set off a collective wail as the cast of their heads let it be known that tragedy had struck.

When they realized Lama Tashi and Yeshe were injured and that the third one being carried was Tulshuk Lingpa and that he was dead, the cries echoing off the surrounding mountains made it sound as if the mountains themselves were crying.

As Dorje Wangmo, Tinley’s mother-in-law, told me, ‘Only the children weren’t crying because they were innocent.’

Tulshuk Lingpa died in his forty-ninth year, a particularly dangerous year by Tibetan reckoning. In Tibetan it is known as a

kak

year, a multiple of twelve plus one. He died on the twenty-fifth day of the third month of the Tibetan calendar, corresponding to Saturday, 18 May 1963.

Death ceremonies for a high lama are very elaborate. For seven days they chanted over the body. They offered incense and butter lamps, and prayed continually. On the seventh day Kunsang, his only son, put a flame to his father’s body and it was cremated.

Some of Tulshuk Lingpa’s ashes were mixed with earth and formed into a stupa at the spot. Some were scattered on the mountain. The rest Kunsang brought to some of the holy places in India—the Ganga River in Banaras, Allahabad (where the Ganga and Jamuna rivers meet) and to the mouth of the Ganga south of Calcutta.

CHAPTER TWENTY ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY ONE

The Aftermath

‘The only paradise is paradise lost.’ —Marcel Proust

‘When the death ceremony was completed and they cremated the body,’ Dorje Wangmo, Tinley’s mother-in-law from Bhutan, told me, ‘it was like a bomb blast. Everyone just dispersed in every direction, without following one another.’ Those from Bhutan returned to Bhutan, those from Sikkim travelled via Dzongri and Yoksum to their villages there.

Dorje Wangmo’s husband wanted to return to Bhutan but she said no, and insisted they go on a pilgrimage. So they travelled together with a few monks west towards Mount Everest. In a place called Walung they found an abandoned monastery where they stayed for six or seven months performing pujas and religious fasting. To return to Sikkim they had to sell everything they had, first their meager jewelry and finally their clothes—everything but what they wore on their backs. When they reached Singtam, a market town in Sikkim on the Teesta River, they had nothing left and could proceed no further. So they collected wild fruits in the forest, laid out a cloth in the market and sold them.

When Dorje Wangmo returned to Sikkim, she was forty years old and pregnant with her first and only child, who was later to become Tinley’s wife. She has always considered her daughter a gift from Mount Kanchenjunga.

‘There was one couple,’ she told me, ‘a monk and nun from Bhutan, who decided to attempt opening the door to Beyul by themselves. So when the cremation was through, they carried a sack of

tsampa

, bedrolls and tin plates with them. They followed the tracks left in the snow by those descending with the dead and injured, and after two days they reached the cave where Tulshuk Lingpa and his followers had lived for three weeks.’

Dorje Wangmo started laughing at the recollection, and her eyes got a faraway mirthful look, sparkling with possibility.

‘From there,’ she said, ‘they disappeared. No one knows what happened to them. Their plates and bedrolls were found in the cave but they disappeared without a trace. Perhaps they made it. We’ll never know.’

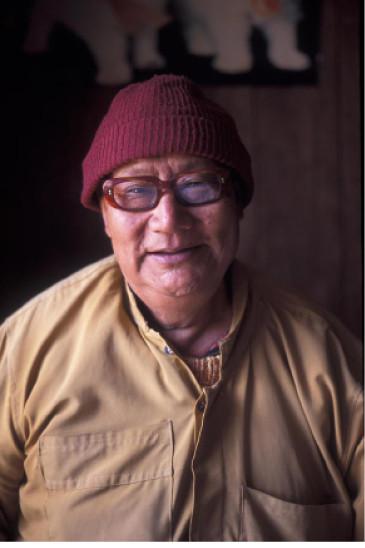

Dorje Wangmo, Gangtok Sikkim

Atang Lama was in his early thirties when he first met Tulshuk Lingpa. He was seventy-four when I met him. He had grown up in Sinon and also lived in Tashiding.

‘That first trip to Kanchenjunga,’ he told me, ‘after which everybody thought Tulshuk Lingpa had failed and the rumors started to fly that he was a spy, was the beginning of difficulties. I was on that first trip along with Géshipa, Kunsang and the others. What struck me most was that the

khandro

had told him in a vision where to go and when he looked down the Kang La Pass into Nepal—and remember, he’d never been there before—he knew the name of the place was Tseram. I was a local boy so I knew. Just when others began to doubt, I knew first-hand the lama’s powers. What the others didn’t know was that he was only finding the way. That was the purpose of the first trip. Though people spoke ill of him, they were only the people who didn’t know him. Whoever came to see him became his followers. Such was the power of his personality. I saw him put his footprint in that stone. It was as if a fire was burning. But then the guy from the king said, “No, I haven’t seen it.”

‘I followed Tulshuk Lingpa to Nepal when he fled Sikkim. I was from a good family. We had a lot of land. Though we didn’t plant that year, because we were going, we didn’t have to sell our land either. I was in Tseram when news came of his death. When those of us who were from Sikkim were returning home after the body was cremated, we hid in the forest during the day and travelled only by night.

‘We weren’t afraid of meeting a tiger in the jungle ,’ he said with a laugh, ‘only of meeting other human beings. We sneaked back to our villages because we were afraid of being caught by the king, whom we had disobeyed by going. He had warned us not to go. Our fields were lying fallow. When we returned, you can be sure we were subject to the ridicule of our neighbors who had thought Tulshuk Lingpa mad all along.’

There was something in Atang Lama’s tone as he recounted this failure to reach Beyul—the way he described sneaking through the forest by night and hiding during the day—that was tinged with embarrassment, as one might have while recounting a childhood prank.

‘In those days,’ he told me, ‘the king would come once or twice a year to Tashiding, and the next time he came he held a public meeting and chided us.

‘“Don’t go off chasing after every lama that offers you a ladder to the moon from the top of a mountain,” the king told us. “It is very cold up there, and you could have died. When Tenzing Norgay climbed Mount Everest, he knew what he was doing. He had the proper boots; he had the proper clothes and equipment. The only miracle is that more of you didn’t lose your lives. If the way opens, why should only you from the villages go? I would also be going, believe me! Next time listen to me, and don’t go chasing after mad lamas.”

‘That’s what the king told us the first time he visited Tashiding after we returned. He also told us that we were then forgiven, and the matter was dropped.’