A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (42 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

‘Jinda Wangchuk had so lovingly walled in the front of the cave, put in windows and internal walls. Now the door was both ajar and askew, hanging by a single hinge. The glass in the windows had been stolen or smashed by stones, the frames left broken and rotting. Stepping inside, I felt as empty as the house itself. The wood-frame walls were all leaning dangerously to the side, the very image of desolation. Not one cup remained on a shelf. Not one spoon. It was empty and damp; leaves crunched beneath my feet. Blinded by tears images flashed through my mind of our departure, of how we had already felt triumphant by the fact of our leaving.

‘My eyes were now smarting from the salt of my tears. I fled back outside where the sharp sun blinded me completely.

‘I heard a voice: “Hey, aren’t you the Prince of Shambhala?”

‘Wiping my eyes with the back of my hand, I saw a young man hanging back. His body was half-hidden by a bush. I recognized him dimly. He had been changed by the intervening years as I too must have been changed.

‘I didn’t know what to answer. “Y-yes,” I finally said. “I am.”

‘“You’re back? What happened?”

‘Suddenly I felt dizzy, as if my entire life was spinning and I was in danger of falling off that cliff directly into the Beas River.

‘“I’ve got to get out of here,” I told him, “It’s all so changed. Help me, please. Help me back up the hill. I never should have returned.”

‘He thought I was crying because I wanted to move back into the cave and had nowhere to sleep the night. “Don’t worry,” he told me. “You can sleep in my family’s house, and if you want, we’ll rebuild the cave.”

‘I slept that night in Manali.

‘The real purpose of my visit wasn’t nostalgia but business—the apple business. The next day I bought woven sacks in the market and I thought I’d be smart and buy my apples directly from the farmers. So I walked down the valley with the empty sacks on my back until I came upon an apple orchard and I bought enough ripe red apples to fill my sacks. It was difficult after that to transport both myself and my sacks but I managed to find a truck that brought me to the railhead on the plains, some eight hours away. I bought a second-class ticket that would take me the thousand or so miles to the railhead below Darjeeling and sat with my sacks on the slowly moving train, feeling rather satisfied with myself for being so smart as to even think of going where apples were grown in order to get my supply.

‘There were no direct trains, so I had to switch trains often. It was not easy with sacks of apples, each weighing as much as I did. I ended up in the passageway of one train, sitting on my sacks. A man sitting next to me on his suitcase started up a conversation.

‘“What is your work, my friend,” he asked me.

‘“Business man.”

‘“What kind of business man?”

‘“Fruit business man,” I told him, proudly patting the sacks of apples.

‘“I see,” he said, and by the smile on his face I could tell he meant trouble.

‘“Where did you buy your fruit?”

‘“Manali.”

‘“Where will you sell it?”

‘“Darjeeling.”

‘“Ah,” he said, laughing at me and pointing out the absurdity of my venture to everyone else in the compartment, “that’s very near!” Even the poorest beggar in that second-class compartment laughed at the absurdity of my venture.

‘I hadn’t factored in the cost of my tickets and my time when I figured out my profit, so of course I made none. I guess I was slow, for after selling those apples in Darjeeling at a loss, I returned to Kullu to do it again. I wanted to make sure it was a complete failure, which of course it was.

‘In the end, I figured it out: No profit in apples.’

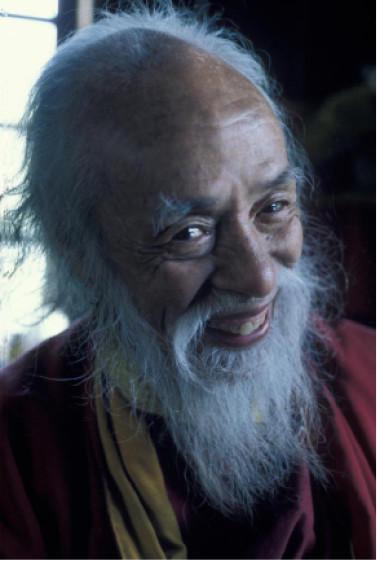

Lama Changchup, Kalimpong, 2006.

Lama Changchup was with Tulshuk Lingpa all the way back in the Pangi days, even before Tulshuk Lingpa cured the people of Simoling of the leprosy and moved there. He remembers Kunsang as a young boy. He used to play with him in the snow and taught him to write in Tibetan. I met Lama Changchup in Kalimpong, where he moved after Tulshuk Lingpa died to be close to his root guru Dudjom Rinpoche. He has the reputation of being a very serious practitioner.

I asked Lama Changchup whether he followed Tulshuk Lingpa to Sikkim.

‘I didn’t go,’ he told me. ‘I was at his monastery in Simoling when Tulshuk Lingpa left for Sikkim. He knew I wasn’t going, and he asked me to stay in Pangao so I went there. I never saw him again.’

‘Why didn’t you go?’

‘I didn’t believe in it. I didn’t think it would work.’

‘Were there many people in Simoling who didn’t believe?’

‘I think I was the only one! Beyul exists for sure. It exists in Sikkim, near Kanchenjunga. But who will go there—that’s another story. You hear that two or three people have gone. One hears stories but nobody really knows. There are many beyuls. It all depends on your karma. Guru Rinpoche wrote about it. I had read in the scriptures that it isn’t so easy to go. You have to be very good in your dharma practice. The time has to be right. You cannot just go there with hundreds of people. Tulshuk Lingpa was a very great lama and he carried his lineage but when it came to Beyul …

‘Tulshuk Lingpa’s mind was pure, and he had good intentions. But there were too many people around him, and they didn’t all think the way he thought. Everyone has a different mind. How could they all have the same mind like him? Though many of those around him weren’t prepared, his mind was quite good and pure. Dudjom Rinpoche and Chatral Rinpoche—they both warned Tulshuk Lingpa not to go so fast but those around him forced him to go.’

‘Kunsang said Tulshuk Lingpa was a crazy lama, always having visions and falling into a trance,’ I said. ‘Was he like this?’

‘How can we know what a lama as high as Tulshuk Lingpa sees inside, what visions they have? They are big lamas, and they see things; but unless they write them down we cannot know. The work we do with our hands—that we can know. I don’t know what is happening in your mind. If you can’t see it with your eyes, how can you know?’

‘Many of Tulshuk Lingpa’s disciples say he made it to Beyul when he died,’ I said. ‘Could this be true?’

‘When you are dead there is no Beyul.’ Lama Changchup said curtly. ‘You go to the Shingkam, the pure land, like a heaven. What would you need Beyul for?’

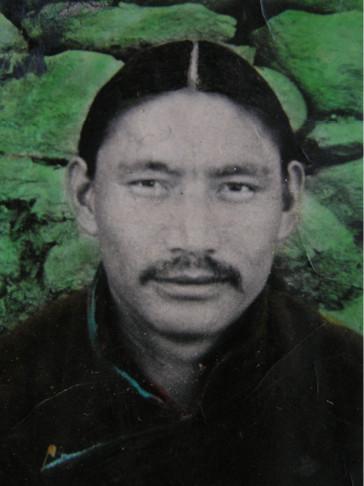

Géshipa.

Géshipa’s yearning for Beyul has not dissipated in the years since Tulshuk Lingpa’s death. If anything, he has become more ardent. For him, the events of the early 1960s did not put an end to his quest to find that elusive gate. To this day he is considering making the journey. When we were visiting him, he even asked Kunsang and me to go with him and attempt an opening of the Eastern Gate. He pointed to a tent and a sleeping bag hanging on a nail by his door, encrusted in sooty cobwebs, ever ready should the opportunity arise. Even though he has a heart condition—his doctor tells him it would probably cause his heart to stop if he attempted high altitudes—he does not care.

‘Even if I die on the way and the bears eat my flesh,’ he said with emotion, his old eyes sparkling, ‘I would gladly offer it to them. Better to die on the way to Beyul than to shrink back in fear.’

His eyes—at once open, childlike, and ancient—peered out of his deeply wrinkled yet innocent face and fixed Kunsang in their gaze. ‘You are Tulshuk Lingpa’s only son,’ he said softly.

Then fixing upon me the same gaze he said, ‘Now your life too is linked to Tulshuk Lingpa’s.’

He looked deeply into each of our eyes in turn.

‘Let us go together to Beyul,’ he suddenly said, his voice quivering with excitement. ‘I’ve been doing the astrological calculations, and next October will be a very auspicious month for opening the Eastern Gate. This could be the last chance within our present incarnations. It is written in one of Padmasambhava’s ancient books of prophecy that once the Nathula Pass is open again for trade with Tibet, it will be next to impossible to get to Beyul. I’ve just been reading it.’ Géshipa pointed in a vague sort of way to a jumble of Tibetan scriptures on a high shelf over his bed wrapped in cloth that were so encrusted in cobwebs and dust that it was clear they hadn’t been touched in years.

‘But your heart,’ I said, ‘your doctor said your heart will stop if you go to high altitudes.’

Géshipa brushed away my concern. ‘Tulshuk Lingpa was attempting to open the Western Gate of Beyul Demoshong,’ he said, his voice at once eager, confident and confidential. ‘Even

he

said the Western Gate was the most difficult to open. The Eastern Gate is the one with least obstructions; it is the easiest.

‘Some years back, two Bhutanese lamas came to see me. They had a scripture I’d never seen before about Beyul Demoshong, and they wanted to discuss it. They weren’t very learned. They were asking me questions and writing down notes. They spent two days with me, discussing the various routes and gates. Early on the third day, they arrived with their bags and told me they were going to make an attempt on the Eastern Gate. That was the last I ever saw of them.

‘It was some time later that I got a visit from some other Bhutanese. It was these two lamas’ families looking for their missing relatives. Since I knew the route they had gone and I couldn’t ask their relatives to risk their lives—the way to Beyul

must

be kept secret—I told them I would go looking for them. So I did. I went to Mangan, Dzongu and Tolung. Then I climbed into the high mountains through thick forests until I got above the trees. There was a lake there and it was very salty, and blue as the sky. There I met a nomad. I spoke to him of Beyul, and he knew the stories. He knew about the Eastern Gate and remembered talking to the missing Bhutanese about it. He had watched the Bhutanese climb a particular valley but they never came down, which was strange to him since the only way out of that high valley was to retrace their steps. But he was a nomad; he had his yaks to attend to, and he never went up to investigate.