A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (16 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

One of Shah Jahan’s own chroniclers wrote blandly that

‘Khusrau got delivery from the prison of existence and instead became confined in the prison of non-existence’

. A Moghul historian, writing later in Shah Jahan’s lifetime, also believed Shah Jahan to be responsible, though he claimed more boldly that Khusrau’s death had been necessary for the empire’s security. Whatever the actual circumstances, Khusrau was undoubtedly murdered, very probably by his brother. Shah Jahan had on several previous occasions attempted to gain custody of Khusrau but Jahangir had resisted. He had only agreed this time either because, as alleged in some accounts, he was drunk when Shah Jahan petitioned him or, as seems more likely, he needed Shah Jahan to subdue the Deccan and wished to please him. Nur probably also played a part in securing Jahangir’s consent. As her focus shifted away from Khusrau to Shahriyar, it must have seemed a neat device for removing both Shah Jahan and Khusrau from court and their father.

Shah Jahan certainly had the motive for killing Khusrau, who, despite his blighted sight, was still the eldest son and commanded a following. Furthermore, his abilities far exceeded those of the drunken Parvez and the somewhat dim-witted Shahriyar. His death was, at the very least, convenient for Shah Jahan. It was also consistent with his later ruthless elimination of other family rivals. However, by ordering Khusrau’s murder, Shah Jahan had committed an act that would haunt his reign and establish a bloody precedent among his children. As an unsympathetic early commentator put it, he was

‘laying the foundation of his throne in a brother’s blood’

.

Jahangir himself, slowly recuperating, seems at first to have accepted Shah Jahan’s explanation of Khusrau’s sudden end. However, accounts suggest that a letter from a Moghul nobleman who had been in Burhanpur at the time and believed the death to have been planned changed his view. The emperor wrote angrily to the nobles in Burhanpur,

‘enquiring why they had failed to write to him the truth, whether his son had died a natural death, or been murdered by some one’

. He ordered his son’s corpse to be exhumed and sent to Allahabad for reburial in the garden housing Khusrau’s mother’s tomb. He also ordered Khusrau’s widow and little son to the imperial court, then at Lahore, for safe-keeping.

However, Jahangir was soon facing a further crisis that left little room for reflections on fratricide. Reports reached him that Shah Abbas, the emperor of a renascent Persia, was advancing on Kandahar, a Moghul border post 300 miles southwest of Kabul and defended by only a scant garrison. The city had been a source of grievance between the two empires ever since a humble Humayun had presented it to the Shah in 1545 in return for help in regaining his throne. Since then the city had been batted back and forth four times. Ownership was a point of principle rather than an issue of real significance. Though Kandahar had once been a wealthy entrepôt on the trade route to India, its importance had waned as traders and pilgrims had taken to the sea instead. Nevertheless, Jahangir was anxious to retain the city, particularly since he feared its capture might presage a Persian invasion of his empire. He mobilized an enormous force including ‘artillery, mortars, elephants, treasure, arms and equipment’ and in March 1622 ordered Shah Jahan and his armies from the Deccan to join it.

The summons came at a poignant and difficult time for Shah Jahan and Mumtaz. Only a few weeks earlier, their son Ummid Bakhsh, born on the mountainous route to ‘Paradise-like Kashmir’ two years before, had

‘shifted to the eternal world’

, as the chroniclers euphemistically reported the little boy’s death. He was the second child that they had lost. Nevertheless, Shah Jahan set out at the head of his forces, with the grieving and once again pregnant Mumtaz as ever following loyally behind with the women of the household in curtained howdahs, bullock carts or panniers hanging against the bony ribcages of camels. He advanced as far as the hill fortress of Mandu, some 100 miles northwest of Burhanpur, but then paused. The excuse he gave his father was that he wanted to wait until the monsoon rains had passed. Jahangir himself had once written that ‘in the rainy season there is no place with the fine air and pleasantness of this fort’ with its airy buildings surrounded by large lakes. However, Shah Jahan also chose this moment to make a series of demands of Jahangir. He asked to be given sole command of the Kandahar campaign and to be appointed governor of the strategic province of the Punjab that would be to his rear as he marched northwest to Kandahar. Most important to him of all, perhaps, was the huge Rajput fortress of Ranthambhor in Rajasthan, seized by Akbar fifty years earlier, which he demanded as a safe refuge for Mumtaz and their children.

Shah Jahan’s conditions reflected his belief that his stock at court was falling. No new honours – either literal or metaphoric – had been heaped on him to mark his victories. Neither had he been recalled to his father’s side. Furthermore, the long march to Kandahar would isolate him from the power base he had been consolidating in the Deccan and leave him vulnerable. At the same time, it could hardly have escaped his notice that Nur’s position had been yet further enhanced. Jahangir had awarded her all of her father’s money and lands, ignoring the custom whereby such assets reverted to the Crown to be apportioned at the emperor’s pleasure among all the deceased’s family. Even more significantly, Jahangir had ordered her drums to be beaten immediately after his own in court ceremonials. It must have seemed to Shah Jahan that, as he marched from one distant campaign to the next with Mumtaz, Nur was profiting from his extended absence, tightening her already forceful grip on government. Later, when Shah Jahan was emperor, his official chronicler blamed his fall from grace on those at court

‘whose coin of sincerity was impure and who had been suffering from the torture of jealousy for a long time’ and who estranged Jahangir from his son, thereby inflaming ‘the fire of intrigue and disturbance which kept burning in Hind for the next four or five years’

. Although he did not say so, the writer clearly meant Nur and her faction.

Jahangir’s response to Shah Jahan’s requests, no doubt encouraged by Nur, was unsympathetic. ‘His report was read, I did not like the style of its purport nor the request he made, and, on the contrary, the traces of disloyalty were apparent …’ he wrote. Jahangir was further angered by news that Shah Jahan had seized lands belonging to Shahriyar and Nur and that his men and Shahriyar’s were brawling openly so that ‘many were killed on both sides’. Deciding that his son’s ‘mind was perverted’, the emperor ‘warned him not to come to me, but to send all the troops which had been required from him for the campaign against Kandahar. If he acted contrary to my commands, he would afterwards have to repent.’

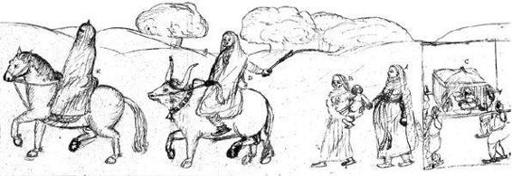

Peter Mundy’s sketch of Moghul women on the move

.

In his irritable and agitated mood, Jahangir revoked the vow he had made five years earlier, when Shah Jahan’s son Shah Shuja had fallen so ill, to give up hunting if he recovered, writing that as ‘I was greatly distressed at [Shah Jahan’s] unkind behaviour, I took again to sporting with a gun’. A more serious signal of his displeasure was that, in August 1622, he decided to hand command of the Kandahar expedition to ‘my fortunate son’ Shahriyar. A delighted Nur gave her husband a pair of ‘priceless’ Turkish pearls that very day. Jahangir also transferred the traditional fief of the heir apparent, Hissar Firoza, which he had bestowed on Shah Jahan fourteen years earlier, to his youngest son. There could have been no clearer statement of intent.

Suspecting correctly that he had gone too far, Shah Jahan apologized to his father and was shocked to find that it was too late. Jahangir wrote, ‘I took no notice of him, and showed him no favour.’ Just as years earlier he had hardened his heart against Khusrau, he now turned his face from the most talented, and once the most beloved, of his sons. Ironically, it was at about the same age as Shah Jahan – thirty years old – that he had staged his own coup against his father, Akbar. Perhaps this fact did not escape him.

In late 1622 Mumtaz gave birth to a son, but the child died before he could be named. Sorrow at the loss, and a growing fear of what would become of his family if he did not act decisively, perhaps contributed to Shah Jahan’s next move – open rebellion. It was a dangerous stratagem, which he would not have embraced without careful thought, but Shah Jahan knew his father’s powers were waning and that many others, like himself, resented Nur’s influence over the emperor and might be induced to declare in his favour. He also knew he could for certain rely on the loyalty of the amirs and officers in the Deccan and in Gujarat, of which he was governor. Therefore, in January 1623, Shah Jahan made his decision and with Mumtaz, their children, and an army of supporters, set out northwards from Mandu to Agra. Rebellions need funds and he was intent on seizing the imperial treasure that informants told him was about to be despatched from the Agra fort to Lahore to finance the Kandahar campaign. According to some accounts, it was Mumtaz’s father, Asaf Khan, who secretly tipped him off about the shipment.

Asaf Khan must certainly have been watching events with growing concern. He had inherited none of his father’s riches – everything had gone to his sister Nur. More significantly, Nur’s blatant manoeuvrings to supplant his son-in-law with her son-in-law in Jahangir’s affections meant that her daughter Ladli, and not his beloved Mumtaz, would become empress. Asaf Khan was too skilled and cautious a courtier to make an open move just yet, but providing a little covert assistance to the prince he privately wished to be the next emperor must have seemed only prudent.

Reports that Shah Jahan had heard that the treasure had been sent for and was marching on Agra further enraged Jahangir, who declared that his rebellious son ‘had taken a decided step in the road to perdition’. ‘Fire had fallen into his mind’, he raged, and he had ‘let fall from his hand the reins of self-control’. Jahangir turned southwards to confront him, relegating ‘the momentous affair of Kandahar’, which had in any case fallen to Shah Abbas the previous June, to a literary tussle. In a letter oozing ritual courtesies, Jahangir hailed the Shah as ‘the splendid nurseling of the parterres of prophecy and saintship’ but peppered his text with subtle insults implying he was being greedy and grasping. Why, Jahangir enquired of Shah Abbas, did he want such a ‘petty village’ as Kandahar? Surely it was beneath his dignity?

‘What shall I say of my own sufferings?’ Jahangir complained in his diary as he set out to deal with the wayward Shah Jahan. ‘In pain and weakness, in a warm atmosphere that is extremely unsuited to my health, I must still ride and be active, and in this state must proceed against such an undutiful son.’ He ordered that henceforth Shah Jahan should be called

Bi-daulat

– ‘the wretch’ – and railed against his son’s ingratitude: ‘From the kindness and favours bestowed upon him, I can say that up till the present time no king has conferred such on his son.’

Jahangir was not in time to forestall Shah Jahan’s attack on Agra. His son plundered the city but failed to capture either the fort or the treasure waiting to be shipped to the Kandahar campaign. Jahangir’s ministers had prudently decided not to risk sending the latter from the fort. Instead they had concentrated on strengthening the fort’s red sandstone towers and thick gates to help them withstand attack. Disappointed though not downcast at his lack of success, Shah Jahan wheeled his forces northwards towards Delhi to engage the imperial troops advancing under Jahangir. To many still wavering on the sidelines of the rebellion, it seemed as if the young, vigorous Shah Jahan would prevail over his ageing father.

On 29 March 1623 the two forces, numbering over 50,000 men in total, clashed on an arid plain encircled by low, barren hills dotted with rocks and scrubby lantana bushes. Neither the ailing Jahangir nor Shah Jahan took part himself. Contrary to expectations, Shah Jahan’s forces were routed and many of his commanders killed, despite the fact that during the battle the leader of Jahangir’s advance guard changed sides, bringing 10,000 soldiers with him. Ironically, Asaf Khan was in command of part of the imperial forces but he was not among those whom Jahangir rewarded for their bravery that day. Doubts about Asaf Khan’s true allegiances may already have been troubling the emperor.

Shah Jahan and Mumtaz fled southwest through Rajasthan, finding a temporary refuge with the new Rana of Mewar (Udaipur), Karan Singh, the wild hill boy whose arrival at court nine years earlier, after Shah Jahan’s defeat of his father, had so amused Jahangir. The young Rana, who had become close to Shah Jahan at court, lodged his guests for four months in an exquisite domed marble pavilion – the Gul Mahal – which he had recently built on an island in the shimmering lake at Udaipur. From here Shah Jahan, Mumtaz and their six young children could gaze out on the surrounding hills and find respite as the summer heat grew fiercer.

For form’s sake, in May 1623 Jahangir entrusted the campaign against Shah Jahan to his second son, Parvez, but its true commander was his most trusted general and childhood friend, Mahabat Khan, who had also been Shah Jahan’s tutor and came from another of the Persian families that had prospered at the Moghul court. Jahangir’s orders were succinctly brutal. Mahabat Khan was to pursue Shah Jahan and capture him alive or, if that proved difficult, to kill him.