A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (20 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

*

Some sources state that Dawar Bakhsh in fact escaped to Persia. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, the French jeweller, later claimed to have encountered him there.

7

The Peacock Throne

D

espite the difficulties of his latter years, Jahangir had not been unsuccessful. Although he had not significantly increased the Moghul territories and had, indeed, lost Kandahar to the Persians, he had curbed the ambitions of the ever-restive rulers in the Deccan, eliminated pockets of resistance in Rajasthan and left a relatively stable empire. His greatest problems had been the rebellions of his own sons – the recklessly impatient Khusrau at the beginning of his reign and ‘

Bi-daulat

’ – ‘the wretch’ Shah Jahan – towards its end.

However, in 1628, as Shah Jahan took control with Mumtaz beside him he was, at thirty-six, in his prime and with no fear of internecine struggles. He was also a very different character from his father. Though both were sensualists, deeply receptive to beauty and appreciative of luxury, Shah Jahan was the more vigorous and self-disciplined. Unlike Jahangir, he had proved himself early on the battlefield and also unlike him he was not an excessive drinker. His historian recorded that despite his father’s urgings he had as a young man drunk only sparingly,

‘during festivals and on cloudy days’

, and in 1620 had renounced wine entirely.

A portrait from the first year of his reign – one of a stream of paintings the image-conscious Shah Jahan commissioned to celebrate his achievements – shows the new emperor in profile against a rich green background. His black, neatly trimmed moustache and beard accentuate a strong, finely modelled face. His large pearl earring and the ropes of pearls interlaced with gems around his neck and wrist and binding his orange turban accentuate rather than diminish his masculinity. Shah Jahan looks, as he no doubt intended, the picture of virility and control, his right hand gripping the hilt of his sword, while his left holds the royal seal on which are etched the names of his ancestors going back to Timur.

For the next eighteen months Shah Jahan, Mumtaz and their children would live a peaceful existence in the Red Fort at Agra. The sumptuous quarters of the imperial harem must have been welcome to Mumtaz. After her peripatetic life as Shah Jahan’s faithful

‘companion during travels’, she could now be his ‘source of solace at home’

. With over one hundred female attendants and a personal staff of eunuchs, she could take her ease in the richly furnished apartments once dominated by her aunt Nur.

Shah Jahan not only loved architecture but was conscious that undertaking building projects was one way in which he could forge for his new reign a new image to distinguish him from his predecessors and inspire awe at his majesty. He was therefore already considering how to remodel the Agra fort to make it yet more impressive in its public apartments and luxurious in its private ones. In particular he decided to replace some of Akbar’s robust sandstone structures with airy

‘sky-touching’

pavilions of pure white marble and spacious courtyards where rose-water fountains would play.

In his private apartments overlooking the Jumna, sunlight was filtered through thin, flower-etched marble screens that reduced its harshness to a soft radiance. The Moghuls lived much of their lives in subdued light. When the summer sun grew too bright their attendants excluded it with silken hangings. To enhance the cooling effect of breezes, they covered the arched windows with

tattis

, screens filled with the roots of scented kass grass, down which they trickled water, creating fragrant draughts of air. In winter they hung velvets and brocades around the royal chambers to keep out the sometimes chilling winds.

Anticipating future visits to ‘paradise-like’ Kashmir with Mumtaz, Shah Jahan also sent orders for extending the Shalimar Gardens. In particular, he ordered the governor of Kashmir to oversee the building of a domed, open-sided black marble pavilion to counterpoint the existing white marble one. Set among vines, apple, almond and peach trees and circular pools of water, the new area of garden was to be named the Faiz-Bakhsh, the ‘Bestower of Bounties’. Mumtaz herself began to lay out a terraced pleasure garden of her own on the banks of the Jumna River – the only architectural project known to have been undertaken by her and probably the only one for which she ever had time and opportunity.

*

Her children had their own adjacent quarters in the harem and were frequently with her. She was especially attached to her eldest daughter, Jahanara, who, in the words of a chronicler, was

‘sensible, lively and generous, elegant in her person’

and who closely resembled her. Mumtaz’s father and mother lived nearby in an opulent mansion along the Jumna and Asaf Khan, in his position of chief minister, was daily in attendance on Shah Jahan at court. According to a court chronicler, soon after his accession Shah Jahan had begun addressing Asaf Khan

‘by the affectionate term “Uncle”, making him envied of all’

.

Another symbol of Shah Jahan’s esteem for his father-in-law were the visits he paid him when, with Mumtaz and his children, he went in state to his house. Asaf Khan observed the ritual niceties:

‘spreading a carpet under his Majesty’s feet and scattering money over his head’ and ‘presenting excellent gifts like gems, jewelled ornaments, fabrics, Qibchaqi horses and mountain-like elephants with gold and silver trappings’

. The imperial family used to remain there for several days of music, dancing and elaborate feasting.

*

Nur was not, of course, a part of this tight-knit family circle. Passion and ambition spent, she had accepted her defeat with characteristic commonsense and retired into obscurity in Lahore with the daughter, Ladli, whom she had failed to make empress in place of Mumtaz. She lived on the pension of 200,000 rupees a year granted her by Shah Jahan. In her distant seclusion she no doubt took comfort in the recollection of the small but exquisite mausoleum she had begun building for her father, Itimad-ud-daula, and her mother six years earlier on the eastern banks of the Jumna and which was completed in the year of her fall.

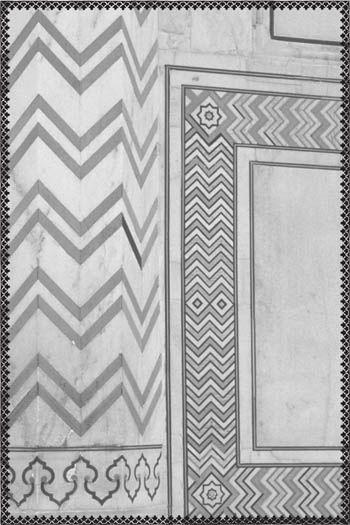

The mausoleum was set within a traditional walled garden, amid channels of cool, flowing water and framed by rows of dark trees. She had created an ethereal structure clad in gleaming white marble, low and square in shape under a canopied dome and with octagonal minaret-like towers at each corner, their tapering pinnacles surmounted with lotus petals. Walls and floors were intricately inlaid, some with geometric patterns, others with the graceful, naturalistic shapes of flowers, utilizing for the first time in India polished semiprecious stones – cornelian, lapis lazuli, jasper, onyx and topaz. This tomb, and another tomb complex built in Delhi at around the same time known as the Chausath Khamba, were the first Moghul buildings to be entirely covered in the white marble that was to become a feature of Shah Jahan’s buildings, including the Taj Mahal. Until this time white marble had, by convention, been reserved for the tombs of Islamic holy men as symbolizing Paradise.

*

The overall effect was of some superbly bejewelled ornament rather than a quite small building.

Nur next devoted herself to the creation of a mausoleum for her husband, who had wished, like Babur, to be buried beneath the open sky. She chose a site in the vast Dilkusha Garden outside Lahore, which she had built and enjoyed with Jahangir in happier days. The design was simple: a cenotaph placed on a platform, itself resting on a giant rectangular podium with minarets at each corner. There was again inlay work, but more restrained than in Itimad-ud-daula’s tomb.

*

Nur also began building her own tomb nearby, modelled on her husband’s. In the surrounding gardens she planted fragrant roses and sweet-smelling jasmine.

Shah Jahan, meanwhile, continued to foster the aura of unprecedented splendour that would characterize his reign. Like his grandfather Akbar, he ordered the key events of his reign to be chronicled in detail and he selected the writers with care, changing them at intervals and approving their work only after regular detailed personal scrutiny.

†

Though writing in the flattering, flowery language of the time, they convey the undoubted magnificence of his court. So do the accounts of bedazzled European visitors. English ambassador Sir Thomas Roe had thought the court of Jahangir at times a little vulgar, but in comparison with what followed it was positively muted. According to one early chronicler,

‘the pompous shows of the favourite Sultana [Nur], in the late reign, vanished in the superior grandeur of those exhibited by Shah Jahan’

.

One of Shah Jahan’s first acts was to commission the famous

Takht-i-Taus

, or ‘Peacock Throne’, to display the most splendid gems in the imperial collection. A true connoisseur, he selected the stones himself from the seven treasure houses spread across his empire. The treasury at Agra alone held 750 pounds of pearls, 275 pounds of emeralds and corals, and topazes and other semiprecious gems beyond count. The eight-foot-long, six-foot-wide, twelve-foot-high throne would take seven years and 1,150 kilos of gold to complete. According to Shah Jahan’s court historian Lahori,

‘The outside of the canopy was to be of enamel work with occasional gems, the inside was to be thickly set with rubies, garnets and other jewels and it was to be supported by twelve emerald columns. On the top of each pillar there were to be two peacocks thick set with gems, and between each two peacocks a tree set with rubies and diamonds, emeralds and pearls. The ascent was to consist of three steps set with jewels of fine water.’

The design may have borrowed from the legend of King Solomon’s throne. This relates how four golden palms, aglitter with green emeralds and dark red topaz, stood around Solomon’s throne – two topped with golden eagles and two with golden peacocks. According to an Islamic tradition the peacock was once guardian of the gateway to paradise. The bird consumed the devil but then carried the devil into paradise in its stomach, there to escape and set his snare for Adam and Eve.

*