A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (21 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

When French jeweller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier saw the throne in 1665, he recorded just one peacock,

‘with elevated tail made of blue sapphires and other coloured stones, the body of gold inlaid with precious stones, having a large ruby in front of the breast, whence hangs a pear-shaped pearl of 50 carats or thereabouts’

. Other accounts of the actual throne also suggest slight variations to the design described by Lahori, but what is clear is that the throne contained the most important collection of gemstones ever assembled in one artefact. Casting a professional eye over it, Tavernier counted 108 large rubies, none less than a hundred carats, and some 116 emeralds, all between thirty and sixty carats.

As the centrepiece, Shah Jahan had to be as impressive as his surroundings. He no longer wore the relatively simple pearltipped heron’s plume of his ancestors in his turban, but an elaborately jewelled spray designed to display his very choicest gems. As a young prince, the jewelled aigrettes brought by European visitors as gifts to his father’s court had caught his eye and now served as a model. The style of the turban itself also changed during his reign. The gossamer-light material weighing only some four ounces was still wound around the head in the same way, but a band of the same fabric or one in a contrasting colour was used to hold the turban more tightly upon the head. Like Jahangir, Shah Jahan wore lavishly embroidered, full-skirted coats of silk or brocade and, in cold weather, soft Kashmiri shawls draped elegantly over one shoulder and quilted overcoats lined with costly furs such as sable. In hot weather, he wore tunics of fine muslin or satin. However, with the eye for the romantic of an English cavalier, he adopted the fashion of fastening his clothes with wide ribbons a foot long, leaving some untied to flutter with negligent grace.

The most spectacular festival after the Nauroz was the ceremonial weighing of the emperor on his birthday. The ceremony, rooted originally in a Hindu tradition, had been adopted by Humayun. Akbar made it more sophisticated, introducing two weighings – a public ceremony on the solar birthday and a private ceremony on the lunar birthday, this last usually conducted within the harem. (The solar and lunar birthdays coincided only on the day the emperor was born and separated thereafter by eleven days a year.) On the first lunar birthday of his reign, 27 November 1628, Shah Jahan was weighed against gold and a variety of other materials. Akbar and Jahangir had only had themselves weighed against gold on their solar birthday, but, reflecting his determined desire to surpass his predecessors in splendour, Shah Jahan included gold in both ceremonies.

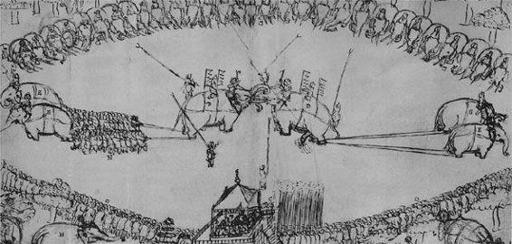

Festivals often concluded with an elephant fight. The elephants were named for their attributes – for example:

‘Good Mover’, ‘Mountain Destroyer’, ‘Ever Bold’

. An earth rampart, four feet high and six feet wide, was thrown up on the plains near the River Jumna. The emperor and women of the court looked down from their respective apartments within the Agra fort, screened of course in the case of the ladies, as two great elephants faced each other from opposite sides of the earth wall,

‘each having a couple of riders [so] that the place of the man who sits on the shoulders, for the purpose of guiding the elephant with a large iron hook, may immediately be [taken] if he should be thrown down’ as a European visitor noted. ‘The riders animate the elephants either by soothing words, or by chiding them as cowards, and urge them on with their heels, until the poor creatures approach the wall and are brought to the attack. The shock is tremendous, and it appears surprising that they ever survive the dreadful wounds and blows inflicted with their tusks, their heads, and their trunks …’ The fights were also highly hazardous for the riders who on the day of the combat took ‘formal leave of their wives and children as if condemned to death’

.

Unsurprisingly at a court where so much depended on outward show, Moghul etiquette was complex and formal. Indeed, it bore many similarities to that of the French court, at that time probably the most sophisticated and regulated in Europe. Knocking on a superior’s door was considered equally vulgar at both the French and Moghul courts. In France, courtiers were expected to scratch on the door with the little finger of their left hand; in Agra, they dropped to their knees and respectfully rapped three times with the back of the hand. At both courts the respective status of individual courtiers was precisely calculated. In France, the height of the chair in which a noble was permitted to sit in the royal presence signalled the level of his prestige; at Shah Jahan’s court, to be allowed to sit at all in the emperor’s presence was a coveted honour awarded to only the very few, reflecting the idea that the emperor was master and everyone else the slave. Not even the royal princes could sit unless so honoured by their father.

Peter Mundy’s sketch of a staged elephant fight

.

Both Shah Jahan and Louis XIV, who came to the French throne in 1643, spent much of their long reigns on public display. Louis’s day was governed by a series of public ceremonies: the

lever

when he arose, relieved himself and was dressed in public, the

debotter

when he changed after hunting, the public procession to the chapel to pray, the receiving of petitions and of foreign ambassadors and the

coucher

when he was disrobed and put to bed in front of his subjects. Shah Jahan’s day began two hours before dawn,

‘while the stars are still visible in the night sky’, when he awoke in the scented air of the imperial harem in the Agra fort, washed and prayed for the first of five times. As the sun rose, he appeared to his people on the

jharokha-i-darshan

, the ‘balcony of viewing’, jutting out over the sandy banks of the River Jumna below. As one of Shah Jahan’s court historians carefully reminded his readers, ‘The object of the institution of this mode of audience, which originated with the late Emperor Akbar, was to enable His Majesty’s subjects to witness the simultaneous appearance of the sky-adorning sun and the world-conquering Emperor, and thereby receive without any obstacle or hindrance the blessing of both these luminaries.’ The emperor’s daily appearance – known as the

darshan

, from a Sanskrit word meaning ‘the viewing of a saint or idol’– also allowed ‘the harassed and oppressed of the population’ to ‘freely represent their wants and desires’. While the masses assembled beyond the fort walls stared up at their emperor, Shah Jahan watched ‘furious wild man-killing elephants’

paraded for his amusement on the riverbank below, soldiers drilling or sometimes the antics of jugglers and acrobats.

Next, Shah Jahan proceeded to the richly carpeted, balustraded hall of public audience, where his nobles and officials awaited him, eyes downcast, absolutely still and silent

‘like a wall’

. Every man’s proximity to the throne was carefully calculated according to his rank. Just before eight o’clock, a cacophony of trumpets and drums signalled the approach of the ‘Lord of the World’ as Shah Jahan stepped through a door from the harem into the throne alcove at the back of the hall. Mumtaz watched and listened through stone grilles cut into the alcove wall as her husband dealt with petitions, received reports, inspected choice gifts and examined horses and elephants from the imperial stables, punishing their keepers if the animals looked malnourished. Any man approaching Shah Jahan was required to make a series of low bows, brushing the ground with the back of the right hand and placing the right palm against the forehead. On reaching the emperor, the man was required to bend yet lower, pressing his right hand to the ground and kissing its back. Under Jahangir he would have been expected to put his forehead to the ground but Shah Jahan had abolished this action, which had originated with Akbar, as a concession to the Islamic clerics, who considered that it too closely simulated prostration in prayer and was therefore blasphemous.

After about two hours, the emperor retired to the hall of private audience with his senior advisers to discuss important matters of state, receive foreign ambassadors and, on Wednesdays, to dispense justice to

‘broken-hearted oppressed persons’

, as his court chroniclers called the supplicants. Shah Jahan, who was a skilled calligrapher, wrote out some of his orders himself. Others were recorded by

‘eloquent secretaries’

and then checked and corrected by the emperor, after which they were

‘sent to the sacred seraglio to be ornamented with the exalted royal seal, which is in the keeping of Her Majesty the Queen, Mumtaz al-Zamani’

. This enabled Mumtaz to review important documents before they were issued. Shah Jahan also gave her the right to issue her own orders and make appointments. In a surviving document of October 1628, she directed government officials to restore a man to a position which had been usurped by another. At the same time she ordered the reinstated man

‘to adhere to the prescribed rules and regulations of His Majesty; to treat the peasants and inhabitants in such a manner that they should be satisfied and grateful to him … and to ensure that not a single rupee of government revenue should be lost or wasted’

. Mumtaz’s round, elegant seal was inscribed with a Persian verse:

By the grace of God in this world Mumtaz Mahal has

become Companion of Shah Jahan the shadow of God

.

Mumtaz was undoubtedly influential – all accounts agree that Shah Jahan sought her advice on key matters. However, she operated very differently from the imperious Nur. Her softer, more discreet approach was a factor of her personality and of the nature of her relationship with the man she had known and loved since both were in their teens. It may also have reflected her awareness that Jahangir had been ridiculed by both his courtiers and foreigners for his obvious and public subjection to Nur’s strident authority. Before his rebellion Mahabat Khan had, according to an anonymous chronicler, complained that no king in history had ever been

‘so subject to the will of his wife’

and, he could have added, so little subject to the views of his nobles. The same chronicler commented,

‘Nur Jahan Begum had wrought so much upon his mind that if 200 men like Mahabat Khan had advised him simultaneously to the same effect, their words would have made no permanent impression upon him.’

Nur had, of course, married Jahangir as a mature, worldly-wise widow. While there seems little doubt that she genuinely loved him, it is also clear that she had an equal affection for power. She had indulged, mothered and protected him, but above all she had controlled him, influencing his decisions and, latterly, taking them for him. Mumtaz did not control Shah Jahan. She was, in every sense, his partner. The physical, emotional and intellectual bonds that had sustained them through exile and flight sustained them now as emperor and empress. Unlike Nur, Mumtaz remained strictly behind the veil and her main desire was for her husband’s contentment. A court poet rejoiced that: