A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (26 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

Shah Jahan never intended Burhanpur to provide Mumtaz’s permanent grave. Her body was disinterred and in December 1631 a melancholy procession set out to bring the dead empress home to Agra. Jahanara did not accompany it but remained to comfort her grieving father, who was staying for the present in the Deccan to wind up his military campaigns. The task of escorting the golden casket in which Mumtaz lay fell to the fifteen-year-old Shah Shuja and to Mumtaz’s friend and chief lady-in-waiting, Satti al-Nisa.

As they travelled slowly northwards, holy men recited verses from the Koran and along the way imperial servants distributed food, drink and silver and gold coins to the poor. As the cortège neared Agra, a court poet described how a great wailing arose:

The world became dark and black in the eyes of its people

.

Men and women of the city, from among the subjects and attendants

,

Applied the indigo of grief to their faces

.

Mumtaz was quickly interred in a

‘small domed building’

on the banks of the Jumna. Yet even this second grave would not be her final resting place. Though still at Burhanpur, Shah Jahan had already planned

‘an illumined tomb’

, a fitting monument to his ‘Queen of the Age’.

At least three motives inspired Shah Jahan’s plans for the building which would almost immediately become popularly known as the ‘Taj Mahal’, from a shortening of Mumtaz Mahal’s name. Foremost was his abiding love for Mumtaz and his desire to commemorate her, but his perception of buildings as symbols of imperial power and prestige and his love of architecture and design for their own sake were subsidiary factors.

Such sentiments are particularly striking given that Shah Jahan was from a society in which men outwardly dominated, where polygamy was common and where admission of feelings for an individual wife and such overwhelming grief at her loss would have been seen as a weakness, not a virtue, in a sovereign. Of course, other rulers in both East and West had expended some of their greatest and most expensive architectural and artistic efforts on commemorating the dead – for example, the pyramids in Egypt, the buried terracotta army at Xian or the Ming tombs near Beijing in China, and the elaborate tombs commemorating dead shoguns built at Nikko in Japan from 1616 to 1636. However, these memorials usually commemorated rulers, rather than their consorts.

Perhaps the only other ruler previously to mark the death of his wife with similar devotion to Shah Jahan was Edward I of England, who, at the end of the thirteenth century, lost his wife Eleanor while she was accompanying him on a royal progress. Theirs, though originally an arranged marriage, was clearly, in the end, a love match. In thirty-six years she had borne him sixteen children, two more than had Mumtaz to Shah Jahan. Edward marked the place where the funeral cortège stopped each night of its 200-mile journey back to Westminster Abbey by erecting an ornate stone cross.

*

In Edward I’s case, demonstrating his royal power and wealth (he spent some £19 million in today’s money) was likely to have been a factor in his actions. The Moghuls, and Shah Jahan in particular, were undoubtedly also conscious of the power of buildings to impress and overawe the public and to demonstrate the insignificance of the subject and the futility of resistance to imperial power. Abul Fazl wrote,

‘Mighty fortresses have been raised which protect the timid, frighten the rebellious and please the obedient … imposing towers have also been built … and are conducive to that dignity which is so necessary for earthly power’

. Shah Jahan’s chronicler Lahori wrote of the emperor’s architectural projects,

‘… construction of these lofty and substantial buildings which, in accordance with the Arabic saying “verily our relics tell of us”, [will] speak with mute eloquence of His Majesty’s God-given aspiration and sublime fortune’

. He described the Taj Mahal itself as

‘a memorial to the sky-reaching ambition’

of Shah Jahan. Yet, though Shah Jahan’s passion for fine buildings and his appreciation of the image they created would coalesce nicely in the huge project on which he was about to embark, they were secondary to his determination to celebrate a matchless love. Otherwise he would not have placed Mumtaz at the centre of his greatest concept.

In planning a mausoleum for Mumtaz Mahal, Shah Jahan was working within a long tradition of tomb building among his ancestors both in central Asia and in India. Admittedly, an order from Genghis Khan that no one who viewed his funeral procession should live to tell the tale is said to have been carried out, and certainly there is no surviving record of where he is buried. However, his descendants left ample evidence of their vigour and sophistication as tomb builders, such as the over 160-foothigh octagonal tomb surmounted by an egg-shaped dome and ringed by eight minarets the Mongol Prince Uljaytu had built for himself in his imperial capital of Sultaniya in Persia in the early fourteenth century.

*

It embodies many elements that would emerge in more polished form in Moghul architecture.

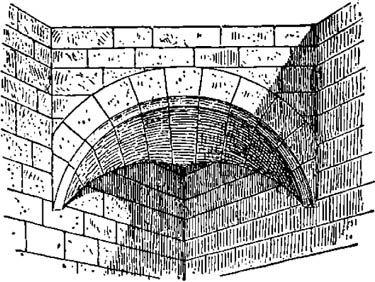

One of the technical limitations overcome by the time of Shah Jahan was how to place a dome on a building whose interior size exceeded that of the dome itself. The problem had been solved as early as the third century

AD

by builders of the Persian Sassanid dynasty, who pioneered the use of a simple arch across the angle of two walls – the squinch – to support the dome. This turned a square into an octagon. If required, further small arches could be added across the corners of the octagon, thus producing a sixteen-sided structure almost approximating the circle of the dome. The invention of the squinch coincided with the development in Syria of the pendentive – a kite-shaped vault supported by a pier over the angle of the square. Designs of squinch and pendentive developed rapidly as builders experimented with construction techniques and artistic possibilities and learned how to place a dome on buildings of any shape and size. The techniques spread westwards as well as east, to be realized in St Sophia in Constantinople, Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence and St Peter’s in Rome, although spires and towers not domes remained the most usual high point of churches in Western Europe.

A squinch

.

Timur, the Moghuls’ ancestor of choice, had been a great builder and constructed a series of royal mausolea, of which his own, in Samarkand, is by far the most imposing. It still stands in the centre of what was a

madrasa

, or Islamic school complex, and has what is known in architecture as a ‘double dome’. By using a double shell with a void between the inner and outer skins, rather than just a very thick, very heavy single shell, designers achieved a much greater difference between the exterior and interior heights of the dome. This enhanced the proportions of the building and also saved considerable weight and structural stress on the rest of the building. Timur’s tomb itself has a great, high, bulbous ribbed dome tiled in bright turquoise blue on the exterior and, within, a lower, hemispherical dome emerging from the same drum-shaped base. The outer shell ensures the visibility and exterior magnificence of an imperial monument, while the lower inner one keeps the interior proportions in harmony.

*

Islamic rulers struggled with the Koranic prescription that tombs should be open to the sky. Some seem to have used a low inner dome, such as in Timur’s mausoleum, as a metaphor for the canopy of the sky, since many such domes are decorated with stars. Others left a gap between the top of the external entrance doors and the lintel to allow fresh air to circulate above the tomb. Babur preferred to leave his own tomb genuinely open. Akbar built a massive double-domed tomb for his father, Humayun. In his own tomb, which he originally designed himself but was altered by Jahangir, his cenotaph sits within an open pavilion, although his actual burial place lies deep below this in the tomb. Jahangir’s large, flat, minaretted tomb built in one of his, and Nur’s, favourite gardens in Lahore also originally had his cenotaph within a pavilion open to the skies but his burial place below, within the tomb. (The cenotaph has since disappeared.)