A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (43 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

The archaeologists’ careful excavations confirmed that the twenty-four-acre Mahtab Bagh was indeed a nocturnal pleasure garden. The moonlight garden was not a Moghul innovation. Hindu rulers had built such gardens long before their coming. They could be enjoyed in the cool of the evening after the day’s heat had subsided, particularly during the nights of the full moon. Gardeners planted them with pale or white flowers to stand out from the dusky background and chose sweet-smelling flowers such as stocks or jasmine to scent the warm, still night air. Another favourite was the champa. The creamy flowers of this member of the magnolia family come out at night and smell richly sweet. Jahangir described how, when in flower,

‘one would perfume a garden’

.

*

The Moghuls enhanced the original Hindu concept, adding running, tinkling water and splashing fountains. They also lined the gardens’ paths with oil lamps and placed them in pavilions as well as in niches behind water features. Often, too, the Moghuls held firework parties in their gardens. Miniatures show women in darkened gardens holding in their hands fireworks that spill a shower of golden sparks.

Working in the Mahtab Bagh in temperatures of over 120°F and digging down to the planting beds, watercourses and walkways of Moghul times, botanical archaeologists found evidence that the champa tree indeed once grew here. They also discovered traces of another sweet-smelling, night-flowering, white-blossomed tree, the red cedar (a member of the mahogany family despite its name), as well as of cashew, mango, palm and fig trees. In addition, they found carbonized seed from the cockscomb, a red-flowered plant which produces masses of seed attractive to songbirds.

†

However, the Mahtab Bagh has a much greater importance for the Taj than this. The archaeologists’ work revealed that the garden was square in shape, with towers at its four corners, only one of which is now intact. They also found signs of a gateway in the middle of the northern perimeter wall. Most interestingly, at the southern end of the garden they unearthed the remains of a raised octagonal terrace overlooking the river and opposite the mausoleum itself. A large octagonal pool was set into the terrace and there were the foundations of a small pavilion on its north side. The pool had contained twenty-five fountains and was surrounded with lotus-leaf designs similar to those used in the Taj Mahal and around pools in other Moghul gardens. When the pool was full, water would have run through a shallow channel at the north of the pool, over a sandstone lip, and fallen down in a small waterfall past a series of niches, in which oil lamps would have been placed by night and flowers by day, into a small sandstone pool at the base.

No water channels remained beyond that point but in the middle of the garden the archaeologists uncovered another raised pool, about twenty feet square and nearly five feet deep. This led them to conclude, very sensibly, that the garden was likely to have been a conventional

char bagh

design, with one of the cross channels flowing from the sandstone pool to the base of the octagonal pool to the pool in the middle of the garden, where another channel would have intersected it at right angles. The archaeologists also found outside the garden’s walls the remains of its water-supply system, in particular a cistern or tank raised on pillars and suggesting, with the remains of other pillars, that the water-supply mechanism resembled that of the Taj complex.

The researchers’ careful measurements showed that the towers marking each end of the waterfront wall of the Mahtab Garden were perfectly aligned with those on the opposite bank at the ends of the Taj and that the north–south water channel – the central axis of the Taj – aligned with the putative channel and existing central pool in the Mahtab Bagh. More significantly, once it was refilled with water, the octagonal pool perfectly captured the reflection of the Taj Mahal. The archaeologists, on the basis of this work, concluded that the Mahtab Bagh was an intrinsic part of the Taj Mahal concept as a whole and formed a moonlight-viewing garden. From the top of the small pavilion at the north of the terrace, Shah Jahan could have watched the Taj Mahal float above the spray from the Mahtab Bagh’s fountains.

Their conclusion that Shah Jahan and his architects had incorporated the Mahtab Bagh within their overall design of the Taj complex, and that they had modified the gardens considerably and added features such as the octagonal pool and pavilions, makes sense of Aurangzeb’s linking of the Mahtab Bagh and the Taj Mahal in his letter of 9 December 1652. In this he described to Shah Jahan how flooding had caused the garden ‘to lose its charm’ at the same time as he reported on leaks in the Taj Mahal. Most importantly of all, the research supports the conclusion that Shah Jahan intended the Taj Mahal to sit at the middle of a vast garden, as in the conventional

char bagh

design, with the north–south water channels of the Taj complex and the Mahtab Bagh both aligned precisely with Mumtaz’s body providing the main axis, but with the River Jumna representing the east–west channel – a truly awe-inspiring if grandiose concept.

Shah Jahan’s creation of such a garden also bears on the enduring belief that he had intended the Taj Mahal for Mumtaz alone and wished to build a separate mausoleum for himself across the Jumna from the Taj. In his book about his travels in India during which he visited Agra in 1640 and again in 1665 (Aurangzeb had imprisoned Shah Jahan by the time of the latter visit), the French traveller and jeweller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier stated:

‘Shah Jahan began to build his own tomb on the other side of the river but the war with his sons interrupted his plan.’

In compiling his account, Tavernier would have drawn on his conversations with courtiers and others in Agra. Local oral tradition supports Tavernier’s account, with the embellishment that the second Taj was to be of black marble and also that Shah Jahan may have intended to link the two with a bridge, perhaps of silver. This story is recounted as firm fact by many guidebooks and most guides, at least as far as it touches on the second black Taj.

Many historians have dismissed the idea of a second Taj because there is no contemporary reference to it other than Tavernier’s and because archaeologists found no foundations for such a building during their recent excavations in the Mahtab Bagh. (The octagonal reflecting pool is sited where the black Taj might have been expected to be.) Convinced there is no evidence of any preparations by Shah Jahan to be buried elsewhere, they have gone on to deduce that it was always his intention to be buried in the Taj. They reject the suggestion that he was squeezed into the Taj by his usurping son as an afterthought by citing a precedent – that Mumtaz Mahal’s Persian grandfather, Itimad-ud-daula, was buried in the same tomb as his wife. They point out that in each case the woman, who died first, lies in the centre with her husband slightly to one side.

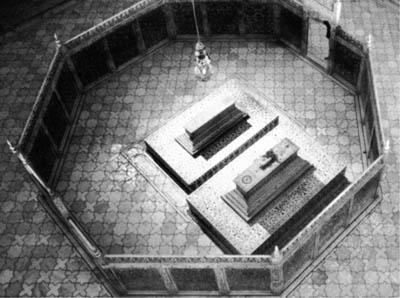

However, before looking at the question of the ‘black Taj’, the argument should be considered the other way round to examine whether there is any evidence that Shah Jahan ever intended to be buried in the Taj Mahal. No court chronicler, no other Indian observer, nor any European, mentions the Taj Mahal as other than the tomb of Mumtaz Mahal until after Shah Jahan’s actual interment. The tomb’s name ‘Taj Mahal’, generally agreed to be a shortening of Mumtaz Mahal’s name, was in popular use well before Shah Jahan’s death and suggests that the tomb was then thought of as hers and to be hers alone in future. It is incontrovertible that Mumtaz’s cenotaph occupies the prime position, aligned as it is along the central axis of the whole complex running from the Mahtab Bagh to Mumtazabad. The placing of Shah Jahan’s cenotaph is the only asymmetrical element in the whole complex. If he had intended himself to be buried in the Taj Mahal, would he not have reserved the central position for himself or planned for Mumtaz and himself to be buried symmetrically, either side of the axis?

Furthermore, Shah Jahan’s cenotaph does appear squashed both into the main chamber of the mausoleum and into the crypt below. In the former, especially when viewed from above, there seems barely room for it between Mumtaz’s cenotaph and the surrounding

jali

screen. If Shah Jahan had intended to be buried by Mumtaz, he would have made the area enclosed by the ornate

jali

screen larger, which there was room to do. Moreover, Shah Jahan’s cenotaph encroaches considerably onto the border of black and white floor tiles around Mumtaz’s cenotaph while having no such border of its own. In the crypt there is scarcely room for a person to pass between Shah Jahan’s grave and the wall, whereas there is some eight feet or so between Mumtaz’s grave and the wall on the opposite side. Again, might not Shah Jahan have built a larger crypt if he had intended to be interred alongside Mumtaz?

View from above of Mumtaz Mahal’s and Shah Jahan’s cenotaphs in the main chamber

.

In addition, the comparison with Itimad-ud-daula’s tomb is not as persuasive as it first appears. The small low tombs of Itimad-ud-daula and his wife, who died within three months of each other, are, unlike those of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal, of the same size and design and are both contained within a single-tiled border on the floor. There is no

jali

screen and plenty of room round the cenotaphs on every side. Bearing this in mind, it is at least as logical to deduce that, when casting around for a burial place for his father, Aurangzeb saw the positioning of his great-grandparents’ cenotaphs as a useful, inexpensive, inconspicuous precedent, as to suggest that the arrangement in Itimad-ud-daula’s tomb supports the argument that Shah Jahan intended throughout to be buried alongside his wife.

On the basis of this evidence it is reasonable to assume that Shah Jahan did not intend to be buried in the Taj Mahal. In that case, where did he intend to be buried? The answer is that we cannot know for certain. However, a stronger case can be made for the black Taj than is sometimes suggested and it has some support, including that of a recent Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, M. C. Joshi, who thought that it must have at least been included at the planning stage, as well as Tavernier’s comments and the strong local tradition.

Shah Jahan was a patron who saw art on a grand scale and the idea of a counterpointing tomb on the north bank of the Jumna would not have been beyond him. The second tomb would have mirrored the Taj Mahal even more perfectly than any shimmering reflection in the Mahtab Bagh’s octagonal pool. Shah Jahan loved to contrast white marble with black. This is exemplified by his building of a counterpointing black marble pavilion in the Shalimar Gardens in Srinagar in Kashmir in 1630, just before Mumtaz Mahal’s death. The Taj Mahal also contains much black marble. For example, the joints between each of the white marble blocks of the four minarets are inlaid with black marble; the low wall around the mausoleum plinth is inlaid with the same material; and the mausoleum itself has black marble in its framing and calligraphy. What better transition to a black Taj over the water?

By general consent the Mahtab Bagh was a pleasure garden. However, in Timurid and Moghul tradition, rulers and nobles were often buried in the gardens they had built for their own diversion while alive. For example, Nur built the tomb of Shah Jahan’s father, Jahangir, in Lahore in one of his favourite pleasure gardens. Jahangir’s father, Akbar, was buried in a garden setting that Akbar himself had chosen during his lifetime. At the time of life when he might have wished to begin work on his own tomb, Shah Jahan had, as Tavernier records, been deposed. The construction of a black Taj, or of any mausoleum in the Mahtab Bagh, was no longer in his power.

*

While the above argument may not be conclusive evidence that a black Taj was planned, it has the advantage of combining known facts and reconciling competing theories. It also has the merit of appealing to the romantic deep in everyone.

Another controversy concerns the purpose of the series of subterranean chambers along the northern riverside end of the sandstone platform that supports the mausoleum on its white marble plinth. There are seventeen chambers in all, linked by short interconnecting passages. The subterranean chambers are connected to the sandstone platform seventeen feet above by two staircases. The chambers have high ceilings, each arching into a kind of dome fifteen feet high at the apex. The ceilings are plastered and decorated with diamond-cut patterns. The lower parts of the walls have red and green borders up to the dado similar to those surviving in Shah Jahan’s buildings at the royal palace at Burhanpur. Above the dado are arched panels sunk into the walls and outlined in red and green. Along the riverside walls of the chambers these arches seem to have been filled in after construction with the small bricks used elsewhere in Moghul buildings. (Viewed from the river, the only external sign of the chambers’ existence is a latticed ventilation screen near where the eastern staircase descends.)

Behind the subterranean chambers to the south, away from the River Jumna, is a separate narrow, high corridor. Measurements show that the combined width of chamber and corridor is twenty-six feet two inches. This means that they stop eight inches short of the foundations of the white marble plinth that supports the mausoleum.