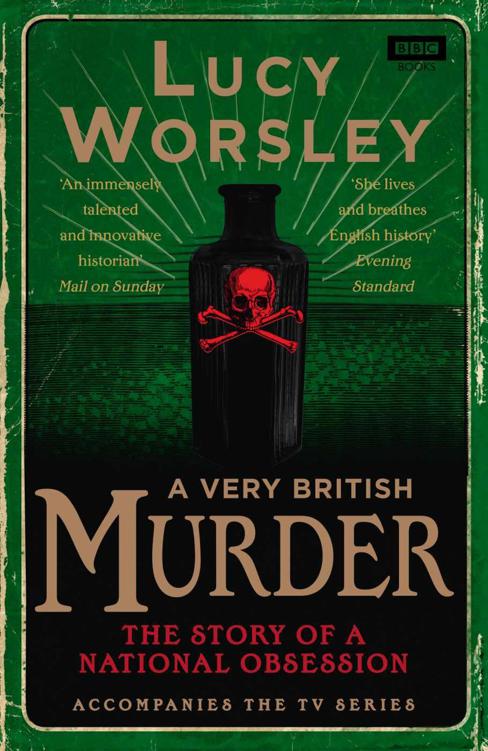

A Very British Murder

Read A Very British Murder Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Contents

PART ONE: HOW TO ENJOY A MURDER

7. Charles Dickens, Crime Writer

11. Middle-Class Murderers and Medical Gentlemen

15. ‘It is worse than a crime, Violet …’

17. The Adventure of the Forensic Scientist

18. Revelations of a Lady Detective

19. The Women Between the Wars

24. The Dangerous Edge of Things

Postscript: ‘The Decline of English Murder’

MURDER

A dark, shameful deed, the last resort of the desperate or a vile tool of the greedy. And yet, an endlessly fascinating storyline in popular entertainment. When did the British start taking such a ghoulish pleasure in violent death? And what does this tell us about ourselves?

In

A Very British Murder

, Lucy Worsley explores this phenomenon in forensic detail. She revisits notorious crimes such as the Ratcliffe Highway Murders, which caused a nation-wide panic in Regency England, and characters such as the murderess in black satin, Maria Manning, who helped bury her lover under the kitchen floor. Our fascination with these dark deeds would create a whole new world of entertainment, inspiring journalism and novels, plays and puppet shows, and an army of beloved fictional detectives, from Sherlock Holmes to Miss Marple. During the birth of modern Britain, murder somehow slipped into our national psyche – and provided us with some of our most enduring and enjoyable pastimes.

A Very British Murder

is a unique exploration of how crime was turned into art, and a riveting investigation into the British soul by one of our finest historians.

Dr Lucy Worsley is a historian and Chief Curator of the Historic Royal Palaces, where she looks after the Tower of London and Hampton Court Palace among others. She has presented numerous television series, including

Harlots, Housewives and Heroines

for BBC4 and

If Walls Could Talk

for BBC1, for which she also wrote an accompanying book. Lucy has also written numerous other books, including

Cavalier: A Tale of Chivalry, Passion and Great Houses.

‘There’s the scarlet thread of murder running through the colourless skein of life, and our duty is to unravel it, and isolate, and expose every inch of it.’

Sherlock Holmes

‘It is Sunday afternoon, preferably before the war … You put your feet up on the sofa, settle your spectacles on your nose, and open

The News of the World

. A cup of mahogany-brown tea has put you just in the right mood. The sofa cushions are soft, the fire is well alight, the air is warm and stagnant. In these blissful circumstances, what is it you want to read about? Naturally, about a murder.’

George Orwell, ‘Decline of the English Murder’ (1946)

IN HIS ESSAY

‘Decline of the English Murder’, George Orwell describes for us the most satisfying kind of killer. Ideally, he’s a solicitor or doctor. He’s chairman of the local Conservative Party, or maybe a campaigner against the demon drink. He commits his crime out of passion for his secretary, but he’s really driven by fear of public shame: it’s easier for him to poison his wife than to go through the public scandal of divorcing her. The archetypal murderer, in Orwell’s mind, was a devious but apparently quiet and respectable little man, rather like Dr Crippen.

But it wasn’t ever thus. Around 1800, people asked to imagine a murderer would have come up with a much more heroic figure: a gallant highwayman, or perhaps a charismatic career criminal who repents on the gallows. They might even have laid eyes upon him themselves, at one of the many crowded and carnivalesque public hangings. And today, by contrast, our scariest and most enjoyable fictional murderers are much less cosy than Orwell’s. They are psychopathic serial killers, nihilistic, motiveless and utterly terrifying.

This isn’t really a book about real-life murderers, or the history of crime – although that’s certainly part of the story. Instead, it’s an exploration of how the British

enjoyed

and

consumed

the idea of murder, a phenomenon that dates from the beginning of the nineteenth century and continues to the present day.

Perhaps appropriately, then, our two bookends will be writers. We’ll start in the late Georgian age, with Thomas De Quincey and his essay ‘On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts’. De Quincey was inspired by the so-called Ratcliffe Highway Murders of 1811, a multiple killing that saw the beginning of the gruesome correlation between lurid reporting of a crime and a massive spike in the sales of newspapers. We’ll end at the Second World War, and Orwell’s essay, in which he laments the declining ‘quality’ of British murders and the rise of a different, more violent, less well-mannered, American-style criminal. Both writers, of course, were satirizing the business of enjoying a murder. And a large-scale, profitable and commercial business it was, too.

As the Victorian age wore on, biographies of murderers were among its publishing sensations. In 1849, as many as two and a half million people bought a rather rushed effort purporting to be

the ‘authentic memoirs’ of Maria Manning, the ‘Lady Macbeth of Bermondsey’, who had helped to kill her lover and bury him under her kitchen floor. In the middle of a cholera epidemic, Manning’s story dominated the news. Her execution was attended by thousands, including Charles Dickens, who found it horrific but nevertheless used Maria as a model for his murderess in

Bleak House

.

Maria Manning’s execution was one of the last female hangings to take place in public. But even after this date you could still meet murderers face-to-face in the pseudo-scientific ‘Chamber of Comparative Physiognomy’, otherwise known as the ‘Chamber of Horrors’, at Madame Tussaud’s gallery. Or else you could watch them re-enacting their crimes in street performances, on the London stage or in puppet theatres. Or you could even buy the merchandising, which included – a particular favourite of mine – ceramic ornaments depicting the houses where notable murders had taken place.

While researching this book, I was also making a television series on the same subject and I particularly enjoyed filming the strange and varied artefacts spewed out by a consumer society’s response to murder. I was ghoulishly pleased to handle the scales used by Thomas De Quincey to measure out the drug to which he was addicted. I myself re-murdered Maria Marten, the Suffolk mole-catcher’s daughter buried in a barn in 1828, by operating the Victoria and Albert Museum’s nineteenth-century puppets representing Maria and her killer, William Corder. It was gruesomely thrilling to handle Corder’s actual scalp, complete with shrivelled ear. It’s on display to the public, as it has been ever since his death, and can be seen in a museum in Bury St Edmunds. It was marvellously horrid

to be in the Chamber of Horrors after hours, and to see the wax figure of Dr Crippen released from his cell, and to look straight into his eyes. Such experiences, mixing horror and fun, were genuinely unsettling and genuinely pleasurable.

The murderer’s rise to prominence in popular culture and fiction was mirrored, of course, by the rise of the detective. He – and eventually she – was greeted with suspicion and the feeling that it was distinctly un-British to ‘spy’ on members of the public. Eventually, society grew to rely upon and to respect the professional crime-solver, but the amateur remained more popular in fiction. I especially like girl detectives, having grown up believing that I was Harriet Vane from the Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries reborn. Employing a female sleuth in a novel allowed authors to send feminine characters bursting out of the usual restrictions of class and home. They could follow suspects, wear disguises, spy on other people and use their intelligence to right wrongs. Even the female criminals of the Victorian age, both in fact and fiction, give voice to passions and complaints not usually heard or expressed by women in society.

Now it’s pretty obvious that the ‘art’ of murder – its depiction in theatre, songs, stories, novels or newspapers – reflects society’s darkest fears back at itself. The Ratcliffe Highway Murders at the start of our period chimed with fears about the newly expanding city, ‘stranger danger’ and urban predators in ill-lit streets. But murder becomes more middle class as the nineteenth century matures. New types of poison (and new developments such as life insurance) provided novel means (and motives) for crime. We think of Sherlock Holmes as living in a world of gas lighting and hansom cabs and opium dens, yet actually many of his cases take him to

places like Leatherhead, Esher or Oxshott, and houses with names like ‘Wisteria Lodge’, ‘Chiltern Grange’ or ‘The Myrtles’. To solve these affairs Holmes leaves Baker Street and London behind, travelling out to the Home Counties on the train.

In the earlier nineteenth century, middle-class murderers could count on the deference that the authorities paid to their very station in society to protect them from the law. The later Victorian period saw more and more middle-class murderers, and murderesses, being caught. And eventually they would find themselves – their concern for respectability and appearances – recreated in the works of Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh and the other great crime writers of the early twentieth century.