A Woman in Charge (47 page)

At one of the inaugural balls

(Getty Images)

The new first lady with schoolchildren in Washington, D.C.

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

Dancing in the White House

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

At Chelsea's high school graduation in Washington, June 6, 1997

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

With Chelsea and Jordan's Queen Noor after a visit to the grave site of her husband, King Hussein

(AP Wide World Images/Enric Marti)

With American peacekeeping troops in Kosovo

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

With Mother Teresa at her orphanage in India

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

With Chelsea at the Western Wall in Jerusalem

(AP Wide World Images)

Hillary's chief of staff Maggie Williams being sworn in to testify at congressional Whitewater hearings

(AP Wide World Images)

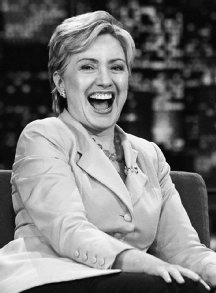

Hillary on

The Tonight Show with Jay Leno

during her first Senate term

(© Reuters/Corbis)

Permanent staff members generally preferred Hillary to the president, whom some of the help judged inconsiderate, rude, and un-presidential. He stayed up until 2 or 3

A.M.

(often discussing policy, playing cards, chewing a cigar, and working crossword puzzles all at once). He allowed junior aides to wander unannounced into the Oval Office. Upstairs, in the family quarters, the ushers and Secret Service agents could not finish their shifts until he was in bed. Only after he retired could they turn off the lights and reduce the number of agents at work. The Bushes and the Reagans, or someone acting on their behalf, had always sent word what time they expected to turn in, so the agents and ushers could plan appropriately. But with the Clintons, particularly given Bill's habits, there was often no word of when this might be. Morning plans were similarly indefinite. He kept in shape by jogging, but whether he felt like a pre-breakfast run depended on the previous night's sleep; hence two teams of Secret Service agents stood ready in the morning, one dressed for running and the other attired in business suits.

Bill found the copious procedures, particularly the requirements of the Secret Service, suffocating. He half-joked about the White House being a high-class “penitentiary.” Though his mother had coddled him, he was uncomfortable with all the personal attention. When he was ready to get dressed in the morning, one of two Navy stewards arrived to put out his clothes, brush them, and make sure everything was in order. When he decided it was time to go to the Oval Office, downstairs, the Secret Service detail that hovered overnight in the bedroom hallway accompanied him to the small elevator. A valet accompanied him with his papers, and four agents covered him front and rear as he made his wayâless than 150 feetâunder the colonnaded walk by the Rose Garden to the Oval. (It was never the Oval Office with the handlersâjust the Oval, and his codename was “Eagle.”) One night, he and a group of aides working in the Oval Office decided to order pizzas. As the president opened his mouth to take a bite, he was tapped on his shoulder by an agent who told him to put the pizza down. The slice had not gone through screening procedures. A steward brought Clinton cookiesâscreenedâto munch on instead. “Why can't I do what I want?” he had once shouted, after being told that his sudden decision to drop in on a friend's book party downtown could not be accommodated by the Secret Service.

The tensions between the Clintons and some members of the household staff and security details were obvious. One usher had never removed the “Re-elect Bush” bumper sticker from his car. Hillary and Bill, not unreasonably, questioned the loyalty of at least a few aides. Hillary complained to Vince Foster that some of the agents seemed abrupt and unfriendly. Their constant presence was intrusive. She became especially concerned about the number of functionaries who hung by doorways, and the agents who were always stationed in the long living area that stretched eastâwest on the second floor, within listening distance of conversations. Four Secret Service agents were assigned to be inside the Oval Office or just outside when the president was there. The potential mischief from conversations overheard was too obvious to ignore. This seemed particularly true after Harry Thomason, who with his wife, Linda, was living part-time in the White House during early 1993, came back one night from a dinner attended by some reporters. He told the Clintons that particulars about the first family's personal life in the White House were being leaked to the press by some of the agents. He urged replacement of the whole White House Secret Service detail. The problem was deemed serious enough for Hillary to tell Foster to solve it, and that she wanted new agents assigned who were more inclined to be sympathetic, perhaps who had worked with them in the campaign.

Among the things Hillary valued most about Foster's judgment were his caution and calm, his ability to look beyond the immediate, to see the big picture. He worried that precipitous replacement of the White House Secret Service contingent, or even a few agents, would inevitably leak to the pressâespecially if Thomason's information had been correctâand would produce a professional and public backlash. He met with David Watkins, another Hope native who was assistant to the president for management and administration (Watkins, Foster, and Mack McLarty had all been student-body presidents at Hope Senior High School), and Mark Gearan. It was agreed that they should watch the situation carefully, but do nothing for the moment.