A Woman in Charge (46 page)

10

A Downhill Path

Weâ¦had to isolate the attacks and focus on the reality of our lives.

âLiving History

T

HE

C

LINTONS,

from their first days after the inauguration, felt they were living in a bell jar. Most of the previous decade they had lived in a governor's mansion modest in comparison with almost all the other forty-nine, a reasonably private family home. The household staff was small. A few state troopers (all personally vetted for their assignment by Hillary and Bill) remained in a separate wing from the living quarters and were available for errands, appearing only when summoned or for receptions. Mornings, Hillary had driven to work in her Oldsmobile, and Bill had driven Chelsea to school. Their lives were minimally affected by security concerns, or (so they thought) the presence of the troopers.

With their move to the White House, the Clintons inherited a grand personal service staff of dozensâmaids, butlers, housekeepers, telephone operators, cooks, ushers, stewardsâand were under the constant supervision of the Secret Service. Most members of the White House personal staff had been enamored of the Bushes, whose WASPish, Junior League formality was an easy fit. During the eight years when George and Barbara Bush had lived in the vice presidential mansion on Massachusetts Avenue, they had adjusted readily to the heavy Secret Service presence, and acclimatized themselves contentedly to the privileges of morning-to-night silver-tray service.

Clinton style and Bush style could hardly have been more different. George and Barbara Bush were far more formal, and their daily regime more predictable: they had stuck to a schedule every day, almost rigidly, making it easy for both the Secret Service and the household staff to serve them efficiently. Bush's aides were decorous and orderly, as had been President Reagan's. The permanent staff identified personally with both families, regarding the twelve-year Republican epoch almost as a single, uninterrupted regency, subject to their guardianship and service. Increasingly, many also came to identify with its political philosophy.

The Clintons weren't imagining a lack of appreciation for their Arkansas-influenced ways, following the Hollywood royalty style of the Reagans, and the

noblesse oblige

of the buttoned-down Bushes. The Clintons liked to kick back. They were used to a thoroughly relaxed atmosphere, even with the troopers, to casual Fridays and late nights out with friends, while the troopers hung back or stayed in the car. The White House Secret Service agents were ever present, trained never to speak casually to the president or first lady, only to respond or lead the way, and they seemed almost hostile in comparison with law enforcement officials assigned to the governor's detail in Arkansas.

Presidents Reagan and Bush, when they left office, were age seventy-seven and sixty-eight, respectively, with wives who had long before seen sixty. The Clintons were young and informal. Twelve-year-old Chelsea was the first young child living in the White House in twelve years, and only the second preteenager since the Kennedy clan had run roughshod on the lawn. But what really distinguished the Clintons was the chaotic atmosphere they and their rather ragged retinue of aides (in comparison with the departing Republicans) introduced.

The many twenty-somethings and thirty-year-olds in Clinton's administration raced around what they called “the campus,” the young men often tieless, the women sometimes in slacks. This youthful cadre, now installed in offices in the West Wing and the Executive Office Building, shared their president's round-the-clock work habits and energy. George Stephanopoulos, the communications director, was thirty-two; Dee Dee Myers, the press secretary, was thirty-one; and Mark Gearan, the deputy chief of staff, was thirty-six.

The White House of January 1993 was surprisingly lacking in high-tech toys like laptops and cell phones. It operated at the mercy of a manual telephone switchboard system that could be maddeningly slow and through which half a dozen presidents had placed and received their routine calls. Bill Clinton, zealous of his privacy and suspicious of a switchboard's capacity for abuse, insisted within weeks of his arrival that he be able to dial out directly, and that operators be incapable of listening to his calls once routed to him. His aides slammed down phones and complained loudly that they needed more lines, fax capability, and portable communications. Some members of the holdover office staff were horrified at what they considered the shockingly unprofessional manner of the twenty-somethings who sometimes chewed gum as they talked, answered telephones like they were in their dorm rooms, and let unanswered messages pile up for days. Soon, the offended holdovers were on the phones to departed colleagues relating anecdotes both fabulous and fact-based about the lack of decorum in the White House. The stories were repeated in newsrooms, at dinner parties, everywhere.

Photo Insert

An early picture of Hugh, Hillary, Hughie, and Dorothy Rodham

Hillary with three high school classmates

(AP Wide World Images)

At Wellesley

(Brooks Kraft/Corbis)

With Bill on the Yale campus

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

Hillary and Bill on their wedding day, October 11, 1975

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

In the governor's mansion with newborn Chelsea, February 1980

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

The Clintons with Vince and Lisa Foster, 1988

(Arkansas Democrat/ Mike Stewart/ Corbis Sygma)

The president-elect with Hillary and Chelsea

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

Chelsea rings a replica of the Liberty Bell to begin pre-inauguration festivities on the Mall, January 1993.

(Smithsonian)

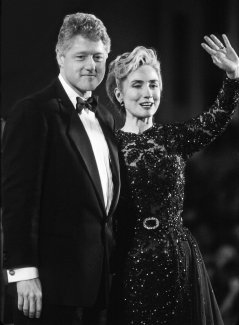

Greeting well-wishers on the Mall during inaugural week, 1993

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

On Pennsylvania Avenue during the inaugural parade

(William J. Clinton Presidential Center)

Chief Justice Rehnquist administers the presidential oath.

(AP Wide World Images)