A World Lit Only by Fire (15 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

B

UT THAT CAME

later. During the early sixteenth century lust, and particularly noble lust, seethed throughout Europe. In France this was

the age of Rabelais, and across the Channel the lords and ladies of Tudor England were establishing a tradition of aristocratic

promiscuity which would continue in the centuries ahead. Yet Rome, the capital of Christendom, was the capital of sin, and

the sinners included most of the Roman patriciate. Among the holy city’s great families, each of which was represented in

the sacred College of Cardinals, were the nouveau riche Delia Roveres, whose cupidity matched their enthusiasm for illicit

public coupling in all its permutations. They occupied the epicenter of Roman society. Two Delia Roveres became popes (Sixtus

IV and his nephew Julius II), their names were on every guest list, and if an invitation to their satyrical parties was ever

refused, the fact is unrecorded.

They had not, however, been pacesetters. That questionable distinction belongs to the notorious Borgias. So many bizarre stories

have been handed down about this hot-blooded Spanish family that it is impossible, after five centuries, to know where the

line of credibility should be drawn. Much of what we have is simply what was accepted as fact at the time. However, a substantial

part of the legend was documented—enough to set it down here with confidence that, however extraordinary it may seem now,

what was believed then was, in the main, undoubtedly true. The tale is a long one. The Borgias had been acting scandalously

at least two generations before Giuliano Cardinal della Rovere, taking the name Pope Julius II, assumed the chair of Saint

Peter in October 1503. He was lucky to have lived that long. Ten years earlier, when the papal tiara had been placed on the

brow of his great rival, Alexander VI, the Borgia pope, Alexander had plotted Cardinal della Rovere’s assassination. At the

last moment Giuliano had eluded the cutthroats by fleeing to France. Then he—himself a future Vicar of Christ—had taken

up arms against the papacy.

The Borgia name had become notorious a half-century earlier, when the reigning pontiff was Pius II. Pius was hardly a prig

—as Bishop Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini he had fathered several children by various mistresses—but when elected pontiff he

had put all that behind him, telling his court, “Forget Aeneas; look at Pius.” In 1460 he himself had been watching twenty-nine-year-old

Cardinal Borgia—the future Alexander—in Siena. Troubled by what he saw there, he sent Borgia a sharply worded letter,

rebuking him for a wild party the prelate had thrown. During the festivities, Pius dryly observed, “none of the allurements

of love was lacking.” He further noted that the guest list had been odd.

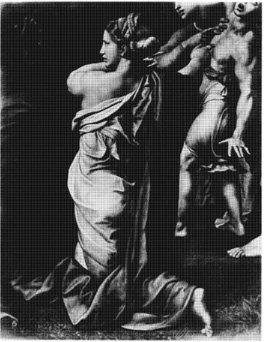

Pope Julius II (1443–1513)

Siena’s most beautiful young women had been invited, but their “husbands, fathers, and brothers” had been excluded.

In the context of that place and time, this was ominous. It could only have been done, as Pius II wrote, “in order that lust

be unrestrained.” Women were accustomed to doing what men told them to do. Lacking the protection of any males in her family,

and intimidated by a formidable cardinal, a girl was unlikely to survive an evening with her maidenhood intact. The mature

woman guest would feel free to ignore the proprieties, particularly when that course was being urged upon her by a prince

of the Church.

Pius warned that “disgrace” and “contempt” would be the lot of any Christ’s vicar who “seems to tolerate these actions.” So,

eventually, it was, but Pius was in his grave four years after the Siena orgy, and a century would pass before another pontiff

agreed with him. All the Holy Fathers of Magellan’s time were uninhibited, but the Borgia pope and his remarkable children

symbolize a time, a mood, and an obsession which, after five centuries, is still fascinating. The reaction against it contributed

to one of those seismic jolts which history rarely notes more than once every thousand years.

R

ODRIGO

L

ANZOL Y

B

ORGIA

, to give him his full name—it was Borja y Doms in Spain—had been elevated to the College of Cardinals by Pope Calixtus

III, his uncle. That was in 1456. No sooner had he donned his red hat than he had removed it, together with the rest of his

raiment, for a marathon romp with a succession of women whose identity is unknown to us and may well have been unknown to

him.

This performance produced a son and two daughters, who were later joined, when he was in his forties, by another daughter

and three more sons. We know the putative mother of this second family. She was Rosa Vannozza dei Catanei, the precocious

child of one of his favorite mistresses. Roman lore has it that he was coupling with the older woman when he was distracted

by the sight of her adolescent daughter lying beside them, naked, thighs yawning wide, matching her mother thrust for pelvic

thrust, but with a rhythmic rotation of the hips which so intrigued the cardinal that he switched partners in midstroke.

Borgia’s enjoyment of the flesh was enhanced when the woman beneath him was married, particularly if he had presided at her

wedding. Breaking any commandment excited him, but he was partial to the seventh. As priest he married Rosa to two men. She

may actually have slept with her husbands from time to time—since Borgia always kept a stable of women, she was allowed

an occasional night off to indulge her own sexual preferences—but her duties lay in his eminence’s bed. Then, at the age

of fifty-nine, he yearned for a more nubile partner. His parting with Rosa was affectionate. Later he even gave her a little

gift—he made her brother a cardinal. Meantime he had chosen her successor, the

Alexander VI, the Borgia pope (1431–1503)

breathtakingly lovely, nineteen-year-old Giulia Farnese, who in the words of one contemporary was “

una bella cosa a vedere

”—“a beautiful thing to see.” Again, as priest, he arranged a wedding in the chapel of one of his family palaces. After

he had pronounced Giulia and a youthful member of the Orsini family man and wife, Signor Orsini was told his presence was

required elsewhere. Then Signora Orsini, wearing her bridal gown, was led to the sparkling gilt-and-sky-blue bedchamber of

the cardinal, her senior by forty years. A maid removed the gown and, for some obscure reason, carefully put it away. She

cannot have thought that Giulia would want to keep it for sentimental reasons, for thenceforth Borgia’s

Giulia Farnese (d. 1524)

new bedmate was known throughout Italy as

sposa di Cristo

, the bride of Christ.

Once he became Pope Alexander VI, Vatican parties, already wild, grew wilder. They were costly, but he could afford the lifestyle

of a Renaissance prince; as vice chancellor of the Roman Church, he had amassed enormous wealth. As guests approached the

papal palace, they were excited by the spectacle of living statues: naked, gilded young men and women in erotic poses. Flags

bore the Borgia arms, which, appropriately, portrayed a red bull rampant on a field of gold. Every fete had a theme. One,

known to Romans as the Ballet of the Chestnuts, was held on October 30, 1501. The indefatigable Burchard describes it in his

Diarium

. After the banquet dishes had been cleared away, the city’s fifty most beautiful whores danced with guests, “first clothed,

then naked.” The dancing over, the “ballet” began, with the pope and two of his children in the best seats.

Candelabra were set up on the floor; scattered among them were chestnuts, “which,” Burchard writes, “the courtesans had to

pick up, crawling between the candles.” Then the serious sex started. Guests stripped and ran out on the floor, where they

mounted, or were mounted by, the prostitutes. “The coupling took place,” according to Burchard, “in front of everyone present.”

Servants kept score of each man’s orgasms, for the pope greatly admired virility and measured a man’s machismo by his ejaculative

capacity. After everyone was exhausted, His Holiness distributed prizes—cloaks, boots, caps, and fine silken tunics. The

winners, the diarist wrote, were those “who made love with those courtesans the greatest number of times.”

Despite the unquestioned depravity of Alexander, the most intriguing figure in the carnal history of the time was one of the

pope’s four children by Vannozza dei Catanei. Born in 1480, the Lucrezia Borgia who has come down to us is an admixture of

myth, fable, and incontestable fact. It is quite possible that she was, to some degree, a victim of misogynic slander. The

medieval Church saw woman as

Eva rediviva

, the temptress responsible for Adam’s fall, and the illegitimate daughter of a pope may have been an irresistible target

for gossip, particularly when she was physically attractive. To this day her reputation is controversial. According to the

Cambridge Modern History

, “Nothing could be less like the real Lucrezia than the Lucrezia of the dramatists and romancers.” Historians disagree, however,

over what the real Lucrezia

was

like. There is certainly evidence that in at least some respects she was what she was thought to have been, but only a few

documents are extant. Although these are shocking, we are largely dependent upon what her contemporaries thought of her. It

was not flattering. Even Rachel Erlanger, one of her more sympathetic biographers, agrees that she had “a sinister reputation”

for “incredible moral laxity.”