A World Lit Only by Fire (17 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

M

EANTIME

, as tumult and intrigue marked papacy after papacy, Italian arts flourished. It is a paradox that painters and sculptors

frequently thrive amid chaos. The deplorable circumstances—the ferment, the vigor generated by controversy, the lack of

moral restraint or inhibitions of any kind—all seemed to incite creativity. Yet it should be added that the greatest of

the artists were shielded from the excesses of the time. To be sure, some of the era’s most gifted men, like everyone else,

lived precariously, even dangerously. The great Albrecht Dürer was reduced at various times to illustrating tarot cards and

designing fortifications for cities. Lorenzo Lotto, near starvation, was forced to paint numbers on hospital beds. Carlo Crivelli

was imprisoned on the charge (which was quaint, considering the period) of seducing a married woman. Luca Signorelli, when

not painting in the Sistine Chapel, was moving from city to city, one jump ahead of the police, and Benvenuto Cellini was

in and out of jails, or plotting an escape from one, for most of his life.

These illustrations are deceptive, however. Dürer prospered through most of his career; Lotto was approaching the end of his

life and had lost his talent; Crivelli’s real crime was that he had bedded the

wrong

wife, a Venetian noblewoman; Signorelli, as a political subversive, was asking for trouble; and Cellini was one of history’s

great rogues—a thief, a brawler, a forger, an embezzler, and the murderer of a rival goldsmith; the sort of character who

in any century, whatever the outrage, is wanted by the police to help them with their enquiries.

More to the point, and more revealing of the time, is the fact that after Crivelli had paid his debt to a hypocritical society

in which a

nobildonna

might betray her

nobiluomo

nightly, he was knighted by Ferdinand II of Naples; and that despite Cellini’s criminal record, he enjoyed the patronage

of Alessandro de’ Medici, Cosimo de’ Medici, Cardinal Gonzaga, the bishop of Salamanca, King Francis I of France, Cardinal

d’Este of Ferrara, Bindo Atoviti, Sigmondo Chigi, and Pope Clement VII, whose other dependents included Raphael and Michelangelo.

That

was

typical of the age. The most powerful men knew artistic genius when they saw it, and their unstinting support of it, despite

their deplorable private lives and abuse of authority, is unparalleled. All the wretched popes—beginning with Sixtus, who

in 1480 commissioned Botticelli, Ghirlandajo, Perugino, and Signorelli to paint the first frescoes in the Sistine Chapel,

and including Julius II, under whom Michelangelo completed the chapel’s ceiling thirty-two years later—were committed to

that greatness. Of course, their motives were not selfless. Immortal artistic achievements, they believed, would dignify the

papacy and tighten its grip on Christendom. Nevertheless they were responsible for countless glories, including the paintings

in the large papal apartment Stanza della Segnatura (Raphael), the frescoes for the Cathedral Library in Siena (Pinturicchio),

and the soaring architecture of the new St. Peter’s (Bramante and Michelangelo). Nor was all Renaissance art supported by

pontiffs. Their fellow patrons and patronesses included the Borgia siblings, and Isabella d’Este of Mantua, whose generous

funding of the brilliant, handsome Giorgione Barbarelli is unmitigated by the fact that she was sleeping with him, since most

of her friends were, too.

In an ideal world, genius should not require the largess of wicked pontiffs, venal cardinals, and wanton contessas. But these

men of genius did not live in such a world, and neither has anyone else. In art the end has to justify the means, because

artists, like beggars, have no choice. Other ages have provided different sources of support, though with dubious results.

Five centuries after Michelangelo, Raphael, Botticelli, and Titian, nothing matching their masterpieces can be found in contemporary

galleries. No pandering to popular tastelessness, adolescent fads, or philistine taboos guided the brushes and chisels of

the men who found immortality in the Renaissance. Political statements did not concern them. Instead they devoted their lives

to artistic statements, leaving time to judge their wisdom.

It is incontestable that the Continent’s most powerful rulers in the early sixteenth century were responsible for great crimes.

It is equally true that had this outraged the painters and sculptors of their time we would have lost a heritage beyond price.

Botticelli pocketed thousands of tainted ducats from Lorenzo de’ Medici and gave the world

The Birth of Venus

. In both temperament and accomplishments Pope Julius II was closer to Genghis Khan than Saint Peter, but because that troubled

neither Raphael nor Michelangelo, they endowed us with the

Transfiguration, David

, the Pietà, and

The Last Judgment

. They took their money, ran to their studios, and gave to the world masterpieces which have enriched civilization for five

hundred years.

T

HE VIGOR

of the new age was not found everywhere. Music, still lost in the blurry mists of the Dark Ages, was a Renaissance laggard;

the motets, psalms, and Masses heard each Sabbath—many of them by Josquin des Prés of Flanders, the most celebrated composer

of his day—fall dissonantly on the ears of those familiar with the soaring orchestral works which would captivate Europe

in the centuries ahead, a reminder that in some respects one age will forever remain inscrutable to others.

Yet almost everywhere else there was an awareness of both endings and beginnings. Enormous cathedrals, monuments to the great

faith which had held the Continent in its spell since the collapse of imperial Rome, now stood complete, awesome and matchless:

Chartres, with its exquisite stained-glass windows and its vast Gothic north tower; Canterbury, the work of over four centuries;

Munich’s Frauenkirche; and, in Rome itself, St. Peter’s, begun nearly twelve hundred years earlier and still, it seemed, unfinished,

for Pope Julius II laid the first stone of a new basilica in 1506, proclaiming indulgences which required all sovereigns in

Christendom to pay for its renewed splendor, thereby demonstrating their royal fealty to a Church still undivided.

But these achievements were culminations of dreams dreamed in other times, familiar and therefore comfortable to those loyal

to the fading Middle Ages. Their day was ending; for every house of God now there were thousands of new words and thoughts

challenging the bedrock assumptions of the past. Among the masses, for example, it continued to be an article of faith that

the world was an immovable disk around which the sun revolved, and that the rest of the cosmos comprised heaven, which lay

dreamily above the skies, inhabited by cherubs, and hell, flaming deep beneath the European soil. Everyone believed, indeed

knew

, that.

Everyone, that is, except Mikolaj Kopernik, a Polish physician and astronomer, whose name had been Latinized, as was the custom,

to Nicolaus Copernicus. After years of observing the skies with a primitive telescope and consulting mathematical tables which

he had copied at the University of Kraków, Copernicus had reached the conclusion—which at first seemed absurd, even to him

—that the earth was actually

moving

. In 1514 he showed friends a short manuscript,

De hypothesibus motuum coelestium a se constitutis commentariolus

(

Little Commentary

), challenging the ancient Ptolemaic assumptions, and this was followed by the fuller

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

(

On the Revolutions of the Celestial Orbs

), in which he concluded that the earth, far from being the center of the universe, merely rotated on its own axis and orbited

around a stationary sun once a year.

In the sixth volume of his

Story of Civilization

, Will Durant notes that Pope Leo X, who succeeded Julius, made no summary judgment of Copernicus. Being a humanist, the pontiff

sent Copernicus an encouraging note, and liberal members of the Curia approved. But the astronomer’s work was not widely circulated

until after his death, and his peers then were divided into those who laughed at him and those who denounced him. The offended

included some of the brightest and most independent men on the Continent. Martin Luther wrote: “People give ear to an upstart

astrologer who strove to show that the earth revolves, not the heavens or the firmament, the sun and the moon. … This fool

wishes to reverse the entire scheme of astrology; but sacred Scripture tells us that Joshua commanded the sun to stand still,

not the earth.” John Calvin quoted the Ninety-third Psalm, “The world also is stabilized, that it cannot be moved,” and asked:

“Who will venture to place the authority of Copernicus above that of the Holy Spirit?”

When Copernicus’s chief protégé tried to get his mentor’s paper printed in Nuremberg, Luther used his influence to suppress

it. According to Durant, even Andreas Osiander of Nuremberg, who finally agreed to assist with its publication, insisted on

an introduction explaining that the concept of a solar system was being presented solely as a hypothesis, useful for the computation

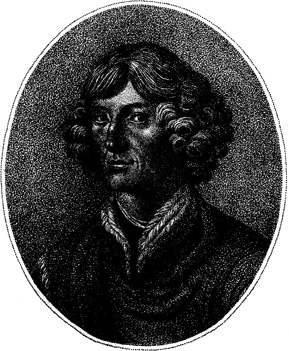

of the movements of heavenly bodies. As long as it was so represented, Rome remained mute, but when the philosopher Giordano

Bruno

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543)

published his Italian dialogues, declaring a rotating, orbiting earth to be an unassailable fact—carrying his astronomical

speculations far beyond those of Copernicus—the Roman Inquisition brought him to trial. He was convicted of being the worst

kind of heretic, a pantheist who held that God was immanent in creation, rather than the external creator. Then they burned

him at the stake. Catholics were forbidden to read Copernicus’s

De revolutionibus

until the deletion of nine sentences, which had asserted it to be more than a theory. The ban was not lifted until 1828.

L

EONARDO DA

V

INCI

(1452–1519), the most versatile creative figure of that age—perhaps of any age—confronted traditional authority with

a more awkward problem. His artistic genius guaranteed his immunity from blacklisting heresimachs; for seventeen years Milan’s

duke, Ludovico Sforza, shielded him by appointing him

ictor et ingeniarius ducalis

, and after Ludovico’s fall Leonardo found other sponsors, even serving Cesare Borgia briefly as his military architect. If

Cesare’s many crimes deserve to be remembered, as they do, so should this generous gesture. Like the patron himself, however,

it was short-lived. Miraculously, the Borgia cardinal manqué had survived to the age of thirty, but now killers with long

knives were closing in. Cesare had celebrated his last birthday. His great protégé found new sanctuaries in the courts of

the powerful, though, they, too, were to prove temporary, because of all the great Renaissance artists, Da Vinci alone was

destined to fall from papal grace.

His disgrace was significant. Leonardo’s transgressions were graver than Botticelli’s or Cellini’s. Indeed, in a larger sense

he was a graver menace to medieval society than any Borgia. Cesare merely killed men. Da Vinci, like Copernicus, threatened

the certitude that knowledge had been forever fixed by God, the rigid mind-set which left no role for curiosity or innovation.

Leonardo’s cosmology, based on what he called

saper vedere

(knowing how to see) was, in effect, a blunt instrument assaulting the fatuity which had, among other things, permitted a

mafia of profane popes to desecrate Christianity.