A World Lit Only by Fire (25 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

I

T WAS PRECISELY

four years away, and the spark which ignited it was the sale of indulgences—specifically, the conduct of the

quaestiarii

, or pardoners, commissioned to distribute them, and the avarice of the papacy. Thomas Gascoigne, chancellor of Oxford, noted

in 1450 that “sinners say nowadays: “I care not how many evils I do in God’s sight, for I can easily get plenary remission

of all guilt and penalty by an absolution and indulgence granted me by the pope, whose written grant I have bought for four

or six pence.” The “indulgence-mongers,” as Gascoigne scornfully called the

quaestiarii

in his account, “wander all over the country, and give a letter of pardon, sometimes for two pence, sometimes for a draught

of wine or beer … or even for the hire of a harlot, or for carnal love.”

John Colet, dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in the early sixteenth century, concluded that the commercialization of indulgences

had transformed the Church into a “money machine.” He quoted Isaiah: “The faithful city is become a harlot”—no one could

doubt which city he meant—and then Jeremiah: “She hath committed fornication with many lovers. … She hath conceived many

seeds of iniquity, and daily bringeth forth the foulest of offspring.” He said, “Covetousness also … has so taken possession

of the hearts of all priests … that nowadays we are blind to everything but that alone which seems able to bring us gain.”

In effect, the practice of indulgences was a form of religious taxation, and its weight bore heavily on those who could least

afford it. Informed Christians deeply resented the gulf between Europe’s hungry masses and Rome’s greed. In 1502 a procurer-general

of the Parlement estimated that the Catholic hierarchy owned 75 percent of all the money in France; twenty years later, when

the Diet of Nuremberg drew up its

Centum Gravamina

—Hundred Grievances—the Church was credited with owning 50 percent of the wealth in Germany.

Peter and Saul (later Paul) had lived in penury. The popes in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries lived like Roman emperors.

They were the wealthiest men in the world, and they and their cardinals further enriched themselves by selling holy offices.

An ecclesiastical appointee had to send the Curia half his income during the first year of his appointment, and a tenth of

it each year thereafter. Archbishops paid huge lump sums for their pallia, the white bands which served as the insignia of

their rank. When Catholic officeholders died, all their personal possessions went to Rome. Judgments and dispensations rendered

by the Curia became official when the applicant sent a gift in acknowledgment, with the Curia fixing the size of the gift.

And every Christian was subject to papal taxes.

Even before he bought his pontificate, Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia’s income had been 70,000 florins a year. But an occupant of

Saint Peter’s chair could do much better than that. Pope Julius

The traffic in indulgences

II formed a “college” of 101 secretaries who each paid him 7,400 florins for the honor. Leo X, more ambitious, created 141

squires and 60 chamberlains in his papal household, and, in return, received 202,000 florins.

Archbishops, bishops—even lower orders of the clergy—grew fat and frequently supported concubines on their fees and tithes.

The laity had first protested their systematic impoverishment in the fourteenth century. Germans had seized tax collectors

from Rome, jailed them, mutilated many, executed some. There, and elsewhere, brave prelates had supported the people. One,

Alvaro Pelayo of Spain, declared: “Wolves are in control of the Church and feed on [Christian] blood!” another, Bishop Durand

of Mende, demanded that “the Church of Rome” remove “evil examples from herself … by which men are scandalized, and the whole

people, as it were, infected.”

The Vatican was unmoved. Over the years it had increased its levies, and that continued. In 1476 Pope Sixtus IV had proclaimed

that indulgences applied to souls suffering in purgatory. This celestial confidence trick was an immediate success; David

S. Schiff has described how peasants starved their families and themselves to buy relief for departed relatives. Discontent

was growing when the wasteful Pope Leo found himself broke—undone by his war against the Duchy of Urbino. Going to the well

once too often, on March 15, 1517, the Holy Father announced a “special” sale of indulgences. The purpose of this “jubilee”

bargain (

feste dies

), as he called it, was to rebuild St. Peter’s basilica. As an incentive donors would receive, not only “complete absolution

and remission of all sins,” but also “preferential treatment for their future sins.”

There was, understandably, no mention of a secret agreement under which the Curia would split the jubilee’s profits with young

Albrecht of Brandenburg, archbishop of Mainz, who was deeply in debt to Germany’s merchant family, the Fuggers. Albrecht had

the pontiff’s sympathy, and he was entitled to it. Albrecht had been obliged to borrow 20,000 florins because that was the

price the pope had exacted for his confirmation as prelate.

The new archbishop chose as his jubilee’s principal agent and hawker one Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar in his fifties.

There were

quaestiarii

whose traffic in indulgences was scrupulous, but Tetzel was not among them. He was a sort of medieval P. T. Barnum who traveled

from village to village with a brass-bound chest, a bag of printed receipts, and an enormous cross draped with the papal banner.

Accompanying him were a Fugger accountant and another friar, an assistant carrying a velvet cushion bearing Leo’s bull of

indulgence. Their entrance into a town square was heralded by the ringing of church bells. Jugglers performed and local throngs

crowded around, waving candles, flags, and relics.

Setting up in the nave of the local church, Tetzel would begin his pitch by opening the bag and calling out, “I have here

the passports … to lead the human soul to the celestial joys of Paradise.” The fees were dirt-cheap, he pointed out, if they

considered the alternatives. Christians who had committed a mortal sin owed God seven years’ penance. “Who then,” he asked,

“would hesitate for a quarter-florin to secure one of these letters of remission?” Anything could be forgiven, he assured

them,

anything

. He gave an example. Suppose a youth had slipped into his mother’s bed

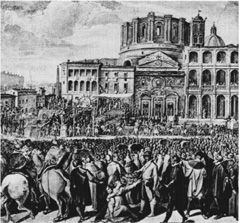

St. Peter’s Square in Rome at the time of the coronation of Pope Sixtus V, in 1585.

and spent his seed inside her. If that boy put the right coins in the pontiff’s bowl, “the Holy Father has the power in heaven

and earth to forgive that sin, and if he forgives it, God must do so also.” Warming up, Tetzel even appealed to the survivors

of men who had gone to their graves unshriven: “As soon as the coin rings in the bowl, the soul for whom it is paid will fly

out of purgatory and straight to heaven.”

In Germany Tetzel exceeded his quota. He always did. This was his profession; he traveled from one diocese to another, raising

funds as instructed by the Curia. Indulgences were popular among the peasantry, but less so among those who, in those days,

formed the opinions of the laity. And this time he was in hostile territory. Northeastern Germany—Magdeburg, Halberstadt,

and Mainz—had been chosen for this extortion because it was weak. France, Spain, and England were strong, and when they

had asked that little be expected of them, pleading poverty, the pontiff had agreed. The decision was not without risk. Antipapal

feeling was strong and vocal in Germany. The papal nuncio to the Holy Roman Empire was worried. That part of the Reich, he

had written the pope, was in an ugly mood. He had therefore urged cancellation of the jubilee.

Leo had ignored him—unwisely, for presently ominous signs appeared. After watching Tetzel perform, a local Franciscan friar

wrote: “It is incredible what this ignorant monk said and preached. He gave sealed letters stating that even the sins a man

was intending to commit would be forgiven. The pope, he said, had more power than all the Apostles, all the angels and saints,

more even than the Virgin Mary herself, for these were all subjects of Christ, but the pope was equal to Christ.” Another

eyewitness quoted the moneyraiser as declaring that even if a man had violated the Mother of God the indulgence would wipe

away his sin.

Nevertheless, Tetzel was probably acting within the letter of his archiepiscopal instructions, and he would have emerged triumphant

once more had he not crossed, or at least approached, a political line. That was the boundary of Saxony, then ruled by Frederick

III, also known variously as Frederick the Wise and, because he was among the privileged few entitled to choose a new Holy

Roman emperor, as elector of Saxony. Frederick was no less reverent than other rulers of his time, no less superstitious —

he had collected nineteen thousand saintly relics in Wittenberg’s Castle Church—and, until now, no critic of

quaestiarii

. However, accounts of Tetzel’s extravagant claims had troubled him. He wanted to keep Saxon coins in Saxon pockets. Therefore

he had declared the friar and his jubilee sale

non grata

in his territory. That was where the peddler of paradise passports blundered. He knew he wasn’t wanted in Frederick’s domain,

but while working the dioceses of Meissen, Magdeburg, and Halberstadt he came so close to the border that some Saxons crossed

over and bought his divine wares.

Frederick was indignant. He considered this an affront. Of far greater moment, several of these Saxon customers brought their

“papal letters” to a slender, tonsured monk of grave aspect and hard eyes—Martin Luther—asking him, as a professor at

Wittenberg, to judge their authenticity. After careful study Luther pronounced them frauds. Word of this reached Tetzel. He

made inquiries. The professor, he was told—correctly—had no intention of offending the Church. Luther was an ardent Catholic,

though inclined, as an academic, to draw nice distinctions. Such a man, Tetzel decided, would be easy to intimidate. Therefore,

in the most momentous decision of his life—and one of the most momentous in the history of Christianity—he formally denounced

him.