A World Lit Only by Fire (26 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

T

ETZEL BECAME

the most famous man to misjudge Professor Martin Luther, but he was far from the first. Luther had always been difficult.

Few were close to him, and none—including, perhaps, Luther himself—understood the tumultuous forces within him. His genius

is unquestioned. He had begun as an Augustinian friar. In 1505, at the age of twenty-two, he was lecturing on the ethics of

Aristotle, using the original Greek text. Two years later he was consecrated a priest, and the year after that, though he

continued to regard himself as a friar or monk, he was appointed by Frederick to the chair of professor of philosophy at Wittenberg,

on the Elbe, about sixty miles southwest of Berlin. Later in his career he translated both the Old and New Testaments into

New High German, a language he virtually created, and composed forty-one hymns, for which he wrote both the words and music.

The most memorable of these, still sung around the world, is “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.”

In his early years Luther’s loyalty to the Vatican was total; when he first glimpsed the Eternal City in 1511, he fell to

his knees crying, “Hail to thee, O holy Rome!” He was already admired as a priest of narrow strength who had risen to early

eminence as much by force of character as by intellect. Nevertheless, deep within him lurked a dark, irrational, half-mad

streak of violence. This flaw, and it was a flaw, may be explained by his origins, which lay in the ignorant, superstition-ridden

depths of medieval society. Luther was the product of a terrifying Teutonic childhood which would have broken most men.

He had been born in 1483, the son of a Mohra peasant who became a Mansfield miner, a husky, hardworking, frugal, humorless,

choleric anticleric who loathed the Church yet believed in hell—which, in his imagination, existed as a frightening underworld

toward which men were driven by cloven-footed demons, elves, goblins, satyrs, ogres, and witches, and from which they could

be rescued only by benign spirits. It was Hans Luther’s conviction that these good witches rarely interceded, though occasionally

they could be propitiated by men living lives of relentless, joyless virtue.

Since children were born wicked, as Hans believed, it was virtuous to beat them senseless with righteous cudgels. However,

Martin, the eldest of seven children, was never a submissive victim. He was not strong enough to overpower his father, but

when the thrashings entered the realm of sadism, the two became, as he later recalled, open enemies. He received no sympathy

from his mother. Though more timid, less irascible, and less worldly than her husband—she spent hours on her knees, praying

to obscure saints—she shared Hans’s convictions, including his belief in the salubrious effect of a vigorously applied lash.

On one occasion, according to Luther, she caught him stealing a nut and whipped him to a bloody pulp.

The Church was the last career such parents would have chosen for their eldest son. He knew it, and that decided him. “The

severe and harsh life I led with them,” he wrote, “was the reason I afterward took refuge in the cloister and became a monk.

” Despite its inspirational beginning, his visit to the Vatican left a poor impression on him, but at the time he kept that

to himself. His colleagues, dazzled by his treatises and his performances in his lecture hall, would have been astounded to

learn that he had never shed the pagan superstitions infused in him even before he had reached the age of awareness—that

a part of him was still haunted by pagan nightmares of werewolves and griffins crouched beneath writhing treetops under a

full moon, of trolls and warlocks feasting on serpents’ hearts, of men transforming themselves into slimy

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

incubi and coupling with their own sisters while in a cave Brunhilde dreamed of the dank smell of bloodstained axes.

Luther was peculiar in other ways. His fellow monks spoke of the devil, warned of the devil, feared the devil. Luther

saw

the devil—ran into apparitions of him all the time. He was also the most anal of theologians. In part, this derived from

the national character of the Reich. A later mot had it that the Englishman’s sense of humor is in the drawing room, the Frenchman’s

sense of humor is in the bedroom, and the German’s sense of humor is in the bathroom. For Luther the bathroom was also a place

of worship. His holiest moments often came when he was seated on the privy (

Abort

) in a Wittenberg monastery tower. It was there, while moving his bowels, that he conceived the revolutionary Protestant doctrine

of justification by faith. Afterward he wrote: “These words ‘just’ and ‘justice of God’ were a thunderbolt to my conscience.

… I soon had the thought [that] God’s justice ought to be the salvation of every believer. … Therefore it is God’s justice

which justifies us and saves us. And these words became a sweeter message for me. This knowledge the Holy Spirit gave me on

the privy in the tower.”

Well, God is everywhere, as the Vatican conceded four centuries later, backing away from a Jesuit scholar who had gleefully

translated explicit excretory passages in Luther’s

Sammtiche Schriften

. The Jesuit had provoked angry protests from Lutherans who accused him of “vulgar Catholic polemics.” Yet the real vulgarity

lies in Luther’s own words, which his followers have shelved. They enjoy telling the story of how the devil threw ink at Luther

and Luther threw it back. But in the original version it wasn’t ink; it was

Scheiss

(shit). That feces was the ammunition Satan and his Wittenberg adversary employed against each other is clear from the rest

of Luther’s story, as set down by his Wittenberg faculty colleague Philipp Melanchthon: “Having been worsted … the Demon departed

indignant and murmuring to himself after having emitted a crepitation of no small size, which left a foul stench in the chamber

for several days afterwards.”

Again and again, in recalling Satan’s attacks on him, Luther uses the crude verb

bescheissen

, which describes what happens when someone soils you with his

Scheiss

. In another demonic stratagem, an apparition of the prince of darkness would humiliate the monk by “showing his arse” (

Steiss

). Fighting back, Luther adopted satanic tactics. He invited the devil to “kiss” or “lick” his

Steiss

, threatened to “throw him into my anus, where he belongs,” to defecate “in his face” or, better yet, “in his pants” and then

“hang them around his neck.”

A man who had battled the foulest of fiends in

der Abort

and

die Latrine

was unlikely to be intimidated by the vaudevillian Tetzel. Yet Luther’s reply to the jubilee agent was not as dramatic as

legend has made it. He did not “nail” a denunciation of the pope on the door of Frederick’s Castle Church. In Wittenberg,

as in many university towns of the time, the church door was customarily used as a bulletin board; an academician with a new

religious theory would post it there, thus signifying his readiness to defend it against all challengers.

Luther’s timing was canny, however. He took advantage of another tradition, the elector’s annual display of his relics on

All Saints’ Day, November 1. This always brought a crowd. Therefore at noon on October 31, 1517, he affixed his (

Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum (Disputation for the Clarification of the Power of Indulgences

) alongside the postulates of other theologians. He did something else. He prepared a German translation to be circulated

among the worshipers who would gather in the morning. And he sent a copy to Archbishop Albrecht, sponsor and secret beneficiary

of Tetzel’s carnival act.

Luther’s theses—he had posted ninety-five of them—were preceded by a conciliatory preamble: “Out of love for the faith

and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions will be discussed at Wittenberg under the chairmanship of

the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology.” It did not occur to him that his position was heretical.

Nor was it—then. The pontiff, he agreed, retained the right to absolve penitents, “the power of the keys.” He simply argued

that peddling pardons like Colosseum souvenirs trivialized sin by debasing the contrition.

However, he then lodged an objection, one Rome could not ignore. The papal keys, he pointed out, could not reach beyond the

grave, freeing an unremorseful soul from purgatory or even decreasing its term of penance there. And while he absolved the

Holy See from huckstering indulgences, he added a sharp, significant observation, which, in retrospect, may be seen as the

first warning flash of the fury he had bottled up within since his hideous childhood. It was, in fact, a direct criticism

of the Apostolic See—breathtaking because it could only be interpreted as the premeditated act of a heresiarch, and thus,

a capital offense. He wrote: “This unbridled preaching of pardons makes it no easy matter, even for learned men, to rescue

the reverence due the pope from … the shrewd questionings of the laity, to wit: ‘Why does not the pope empty purgatory for

the sake of holy love and of the dire need of the souls that are there, if he redeems a … number of souls for the sake of

miserable money with which to build a church?’ ”

T

HE SALE

of indulgences plunged. Fewer and fewer quarter-florin coins rang in the pontiff’s bowl. The jubilee had virtually collapsed;

Tetzel’s spell had been broken. Luther was the new spellbinder—divine or satanic, for opinion was deeply divided—and accounts

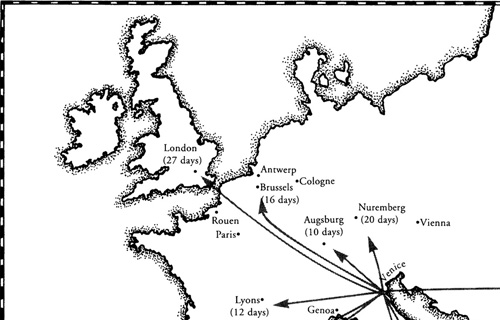

of his audacity spread across the continent with what was, in the early 1500s, historic speed.

As long as a year would pass before the tidings of great events reached the far corners of Europe. Except for the flatbed

presses, which moved at a lentitudinous pace, communications as we know them did not exist. Information was usually carried

by travelers, and trips were measured by the calendar. The best surviving timetables start from Venice, then the center of

commerce. A passenger departing there could hope to enter Naples nine days later. Lyons was two weeks away; Augsburg, Nuremberg,

and Cologne, two or three weeks; Lisbon seven weeks. With luck, a man could reach London in a month, provided the weather

over the Channel was cooperative. If a storm broke in midpassage, however, you were trapped. The king of England, leaving

Bordeaux under fair skies, did not appear in London until twelve days later.

Yet if news was electrifying, it could pass from village to village and even across the Channel, borne word-of-mouth. That

is what happened after Luther affixed his theses to the church door. Before the first week in November had ended, spontaneous demonstrations supporting or condemning him had erupted throughout Germany. Luther had done the unthinkable—he had flouted

the ruler of the universe.