A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (76 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

The Foreign Office had already issued instructions to detain Morgan’s vessel. But by some mysterious chance, the telegram remained in an out-box until after the port’s telegraph station closed for the day. The delay enabled the

Japan

to escape in the early hours of April 1, 1863.

51

Eight days after leaving England, off the coast of Brittany, Matthew Maury’s cousin Commander William Lewis Maury hoisted aloft the Confederate flag, and the

Japan

began its service as CSS

Georgia.

—

The appearance on the high seas of a third Confederate commerce raider ratcheted up the already high tension between the United States and Royal navies. The U.S. blockading squadron at Mobile, for example—which was still smarting from the embarrassment of having allowed CSS

Florida

to escape—started firing live rounds at passing Royal Navy vessels, each time claiming to have mistaken the unambiguous appearance of a British warship for a civilian blockade runner.

18.4

Conversely, British frigates patrolling the Caribbean were as unhelpful as possible toward the U.S. vessels trying to chase down blockade runners.

Admiral Milne, commander-in-chief of the Royal Navy’s operations in North America and the West Indies, was annoyed by his officers’ failure to maintain a strictly neutral stance. He despised the blockade runners and had ordered the fleet to refrain from giving them any assistance. Sometimes the so-called offense against the United States was simply tactless behavior, such as the fraternization between British crews and CSS

Alabama

when she sailed through Jamaican waters in January. But at other times, Milne detected more than a hint of partisanship. In February he removed HMS

Petrel

from Charleston after Captain George W. Watson and his officers became far too friendly with the blockaded townspeople.

53

The last straw was a clearly biased report by Watson about the weakness of the blockading fleet. Milne upbraided him for “mixing himself so conspicuously and unnecessarily with the Confederate authorities,” and ordered Watson to a remote part of the Caribbean. “I cannot trust him either at Nassau or on the American coast,” Milne complained on March 20 to Sir Frederick Grey of the Admiralty.

54

Milne also punished the captain of HMS

Vesuvius,

who had agreed to transport $155,000 in specie past the blockade at Mobile because, allegedly, it was interest owed to bondholders in Britain. (Fearful of the reaction in Washington, Lyons promptly dismissed the British consul who had arranged it.)

Milne made it his general rule to adopt a lenient approach regarding complaints about American harassment of “innocent” cargo ships. He also held firm even when the U.S. Navy widened its net to include merchant ships sailing between the West Indies and the Gulf of Mexico. The chief destination of these ships was Matamoros, a miserable, drought-ridden town on the Mexican border about thirty miles from the mouth of the Rio Grande. Powdery white dust covered every surface in Matamoros, including the hair and clothes of the inhabitants, making them look like the walking dead. The town would have dissolved back into the scrubland were it not directly across the river from Brownsville, Texas, another miserable little town whose existence was saved by the Civil War.

These two places, more than fifteen hundred miles from Richmond, were the only open gates into the Confederacy. The narrow, winding Rio Grande was a neutral river, and so, according to international law, it could not be blockaded. At first the North paid little attention to Matamoros. It was situated in a barren waste that spread for hundreds of miles; there were no port facilities or roads, and its only connection to Brownsville was a rickety ferryboat. But even with these obstacles, cotton sellers were prepared to risk their lives hauling long wagon trains across the Texas plains and over the river. By early 1863, nearly two hundred ships a month were calling at Matamoros, bringing supplies to the Confederacy and leaving with cotton.

Although he could not admit it publicly, Russell was anxious for the sake of the British cotton industry that this tiny chink in the blockade should stay open. He ordered Lyons to protest the U.S. Navy’s habit of seizing any British ship heading toward Mexico. There was no way of proving whether the guns and matériel were destined for the South or for the beleaguered Mexican government, whose twelve-month resistance against a French invasion force was showing signs of fatigue. But Milne was loath to interfere with the practices of the U.S. Navy; HMS

Phaeton

was already cruising the gulf as a friendly reminder of British neutrality. The only help that Milne was prepared to give to British merchantmen was the advice to anchor on the Mexican side of the Gulf, where the U.S. Navy was powerless to molest them.

The fate of several British merchant ships was already worrying the Foreign Office—and the readers of

The Times

—when U.S. admiral Charles Wilkes once again exercised his uncanny ability to create an international crisis. Learning that a British-owned merchant ship called the

Peterhoff

was leaving the Danish island of St. Thomas to sail to Matamoros, Wilkes ordered USS

Vanderbilt

to stop her as soon as she left the harbor. As the

Vanderbilt

approached, one of the

Peterhoff

’s passengers was observed throwing a large packet into the water. Her captain was nowhere to be seen, since he was busy burning papers in his cabin. The captured ship was brought to Key West in Florida on March 10, 1863, where the British vice consul said that the vessel could not possibly have been involved in anything so low as blockade running since Captain Stephen Jarman was a lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve. Moreover, she had been transporting the Lloyd’s insurance agent for Matamoros and a bag of mail from the Post Office. The return of the mail became an instant cause célèbre in England. The poisonous combination of Charles Wilkes and British property provoked

Trent

-like hysteria, with the press insisting that national honor was at stake.

55

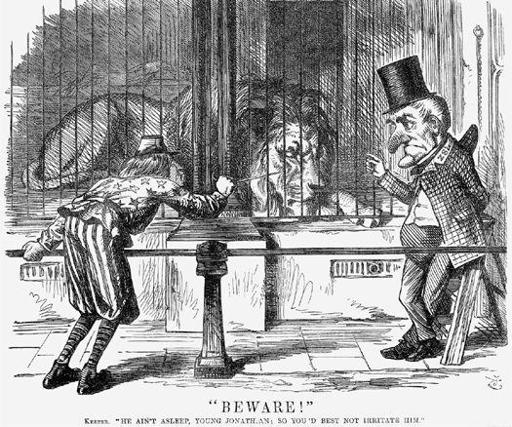

Ill.35

Punch warns the United States not to irritate the British lion, May 1863.

Lyons warned Russell that the mood of the Northerners was just as violent.

56

Whatever their disagreements over the war and the merits of abolition, they were united by their resentment toward Britain. “Everybody is furious with England and with everybody and everything English,” Lyons wrote sadly.

57

The Northern press was claiming that the British were building a navy for the Confederates, supplying their armies, lending them money, and providing moral if not actual support to the

Alabama,

the

Florida,

and the

Georgia.

Lyons telegraphed Admiral Milne to make his fleet battle-ready—once again, the signal for war would be “Could you forward a letter for me to Antigua?”

58

Milne complied, though he was fearful that putting his ships on alert would provoke the very collision he was laboring so hard to prevent.

18.1

Monitor ships were different from ordinary ironclads on account of their heavy guns, revolving turrets, and flat bottoms, which enabled them to lie low in the water.

18.2

Henry Adams was like his father in his tendency to exaggerate the division of opinion between the social classes. Friends, neighbors, and even families disagreed with one another, such as the Devonshires at the top of the scale—where Hartington leaned toward the South, and his brother Lord Frederick Cavendish toward the North—and the Collings family at the lower end, where Jesse Collings, a hardware merchant, bombarded the local press with letters in support of the North, and his brother Henry, a commercial sailor, joined the Confederate navy and fought on board CSS

Merrimac.

18.3

The consuls reported on January 9, 1863, for example, “an armed steamer is to leave Liverpool to-morrow with important dispatches from Commodore Maury (who is still in England), Mason, and Slidell. A man by the name of Hope is the bearer of these dispatches and will go out on the steamer.”

18.4

In New Orleans, a young sublieutenant on shore leave from HMS

Galatea

was beaten up and thrown into the stocks. An investigation revealed that he had been strolling down Canal Street singing rebel songs. The dim-witted officer defended his conduct, saying “I did call them stinking cowards but that was nearly all.”

52

NINETEEN

Prophecies of

Blood and Suffering

Blockade running becomes a serious business—Two cautionary tales—Seward is courageous—General Longstreet feeds an army—A murder—Hooker’s “perfect plan”

I

n London, Benjamin Moran laughed sourly when he read the naïve response of the British vice consul in Florida. There was no doubt that Captain Jarman had been blockade running; Moran had in his possession a copy of the subscription letter offered by the

Peterhoff

’s owners, which stated that the purpose of the voyage to the West Indies was to supply arms to the Confederacy in exchange for cotton. Nor could the uproar over Admiral Wilkes’s action disguise the fact that Bermuda and the Bahamas had become the chief supply depots for the South.

The Bahamas was the preferred route for commercial blockade runners because of their proximity to the Southern coast. It took only three days to sail from Nassau to the main Southern ports. The same trip from Bermuda—which was almost nine hundred miles due east of Charleston—took at least five days and sometimes more in poor weather. But by late 1862, Josiah Gorgas, the Confederate chief of ordnance, had realized that Bermuda’s relative inaccessibility was an advantage for his government since the competition for docking facilities and warehouses was less fierce. The Ordnance Department’s small fleet of blockade runners used the tiny island of St. George, which lay at the top end of the archipelago. Its port was closer to the open sea than the main island’s, and the approach from the South was an easy passage through crystalline waters. On the return journey, the ordnance fleet unloaded its cargoes at Wilmington in North Carolina rather than sailing to Charleston, which was expensive and crowded. Though not as convenient as Charleston—Wilmington was twenty-five miles from the sea, on the east bank of the Cape Fear River—the port could be reached via two different approaches and enjoyed the advantage of being guarded by Fort Fisher, whose large guns could hit any blockader attempting to enter the river.

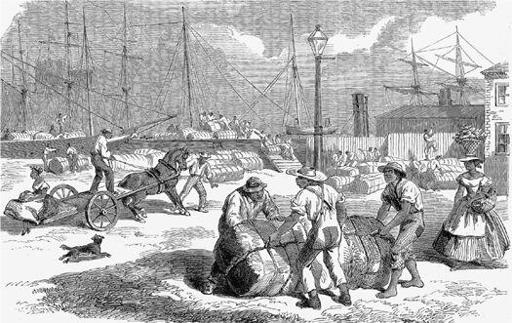

Ill.36

Unloading cotton from blockade runners at the port of Nassau, by Frank Vizetelly.

The supply system between Bermuda and Wilmington was growing so rapidly that in early 1863 the Confederate Ordnance Department appointed Major Norman Walker to oversee its operations on the island. From his headquarters at the Globe Hotel on St. George, the industrious Walker arranged for 80,000 Enfield rifles, 27,000 Austrian rifles, and 21,000 muskets to be shipped in February alone. He also filled orders for steel, copper, and saltpeter and sent hundreds of cases packed with screwdrivers, cartridges, buckles, stirrups, percussion caps, buttons, and all other daily necessities required by the Confederate armies. Soon the U.S. consul in Bermuda reported that Confederate steamers were coming and going with the regularity of mail ships.

1

As he was naturally resented by the locals for his attempts to interfere with this lucrative trade, the consul’s life became a daily round of harassments both petty and great. One morning in March a group of “colored blockade running seamen” took their revenge by loudly singing Confederate songs beneath his window.

2