Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation (4 page)

Read Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation Online

Authors: Mark Pelling

Tags: #Development Studies

It is difficult to estimate the future costs of adapting to climate change. From the more restricted world of disaster management we know that the difference between investing in prevention and the costs of a disaster impact can easily exceed a ratio of 7:1 (DFID, 2004a). The costs of adapting to climate change are more far-reaching. Future demands for adaptation are also to be shaped by the actions we take now to mitigate it. One estimate, by Stern (2006), suggests adaptation costs in the order of 5 to 20 times the estimated costs of containing climate change through mitigation. The economic costs of adaptation are also not evenly distributed worldwide. Using data from past natural disaster events shows that richer nations with an accumulated legacy of physical infrastructure and housing have the most absolute economic exposure. However, these countries also have the assets to adapt (and arguably have substantial power and duty to mitigate, and in this sense have some control over, their own destiny). Poorer countries have less physical assets exposed but economies tend to be more dependent upon primary production and ecosystem services. As a proportion of GDP potential economic losses are highest in low and middle income countries. In addition, it is the same countries – from Africa, Central, South and Southeast Asia and Central America and the Caribbean – that record the highest mortality rates from natural disasters, adding human to economic vulnerability (UNDP, 2004). Past experience and projected risk of human loss through mortality and morbidity are also strongly skewed to poorer countries where income is dependent on primary extraction and where populations are not protected from environmental hazards by safe buildings, infrastructure, health services, and transparent and responsive governance (IFRC, 2010).

Observed data based on losses to past patterns of disaster events is the best guide to current vulnerability and backward looking adaptive capacity, but climate change means past patterns of hazard may not be as useful a guide to the future as had once been assumed; the so-called problem of non-stationarity

(Milly

et al.

, 2008).

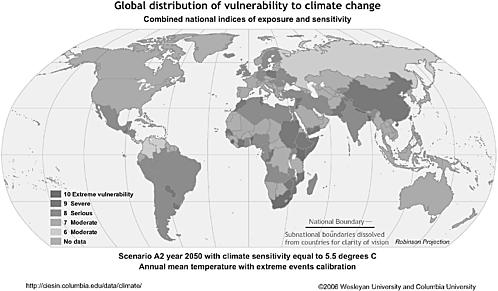

Figure 1.1

shows an example of forward looking assessment of relative vulnerability to climate change and extremes under a warming of 5.5 degrees C. It incorporates adaptive capacity as a component of vulnerability. Vulnerability is calculated based on input variables for human resources (dependency ratios and literacy rates), economic capacity (market GDP per capita and income distribution) and environmental capacity (population density, sulphur dioxide emissions, percentage of unmanaged land). The advantage of this approach is that it is not tied to past experiences of extreme events. Despite this, results largely confirm the burden identified above for poorer countries. High levels of vulnerability are associated with low and middle income countries in South America, southern Asia and Africa. High vulnerability is also found in China and some of Eastern Europe. But this method also suggests North America and Europe are extremely vulnerable, painting a portrait of widespread vulnerability across the globe where adaptive capacity is overwhelmed by climate change even over the next 40 years (Yohe

et al.

, 2006). This is a compelling case for the need for urgent and deep levels of mitigation alongside the need to support adaptation to reduce vulnerability from current and inescapable future climate variability and extremes.

The IPCC (2007) calculates that for the most exposed countries, such as coastal states in Africa, adaptation costs may be as high as 10 per cent of national GDP. For low-lying small island developing states the relative costs are even higher. Oxfam (2008) estimates that at least US$50bn is needed annually to support adaptation in developing countries. UNDP (2007) identifies an additional need of around US$86bn by 2015 (0.2 per cent of developed country GDP) on top of existing overseas development assistance budgets from bilateral and multilateral donors. These are large sums, but not unprecedented. The UNDP (2007) equates its total cost estimate to around 10 per cent of the current military expenditure by OECD countries.

The international architecture for support of adaptation is developing as adaptation rises on the political agenda. The UNFCCC provides one management structure for support of low and middle income countries. Bilateral and multilateral agencies, such as the development banks and other UN agencies, also provide financial and technical support. Investment decisions in the corporate private sector also impact on adaptation, including policy decisions from the insurance and reinsurance sectors, and are likely to increase in importance as businesses in middle and high income countries are forced to adapt. The emerging infrastructure is, however, built around existing poles of power – nation states and the UN system which is beholden to them, or banking interests, with nation states or private investors at the helm. Can these actors be expected to embrace adaptation as anything other than resilience – acts to reinforce the status quo? Indeed should they be encouraged to do so? Asserting more radical change in social and political systems needs to come from below through the actions of people at risk building on existing social and political reform movements.

With the costs of climate change increasing and adaptation being increasingly demanded, meeting the funding gap for adaptation in the short term is a key

Figure 1.1

Global distribution of vulnerability to climate change. Combined national indices of exposure and sensitivity

(Source: Yohe

et al.

, 2006)

challenge. Without additional and earmarked funds for adaptation there is a risk of money being forced from existing overseas development assistance (ODA) budgets. ODA finance is already being squeezed by increased recent demand for humanitarian and disaster reconstruction funding (White

et al

., 2004). Agrawala (2005) has estimated that between 15–60 per cent of official development assistance (ODA) flows will be affected by climate change. This trend is a particular tragedy as ODA is a key mechanism for reducing generic vulnerability to disaster risk and climate change impacts as well as achieving broader human security goals. A range of proposals exists for identifying additional funds. Oxfam (2008) proposes that funding be generated from auctioning a fraction of emissions allocations to developed countries under the post-2012 agreement, including proposed new emissions-trading for international aviation and shipping. Other proposals include increasing the share of the Clean Development Mechanism contributing to adaptation and increasing the role played by private capital through venture capital or commercial loans.

Since its reintroduction into social scientific and policy debates following the Rio Summit, the interests of different analysis have made adaptation a slippery concept. For some, adaptation’s contribution would best be as a tightly defined, technical term (like mitigation in the existing UNFCCC documentation) that can add universal clarity to policy formation including at the international level (for example, Schipper and Burton, 2009). Others, who see adaptation not as a technical category but as a research field, tend to have a wider view. Fankhauser (1998) suggests that adaptation can be synonymous with sustainable development. This challenge was noted as early as 1994 by Burton, just two years after the Rio Summit, and the plethora of interpretations has continued to grow as individual disciplines and intellectual communities have invested adaptation with their own worldviews (Kane and Yohe, 2007).

The adaptation to climate change debate is driven by four questions:

• What to adapt to?

• Who or what adapts?

• How does adaptation occur?

• What are the limits to adaptation?

None of these questions have easy answers.

Climate change itself is agreed to be manifest in at least three interacting and overlapping ways: climate change has come to encompass long-term trends in mean temperatures and other climatic norms, importantly precipitation, and secondary effects like sea-level rise together with variability about these norms from inter-seasonal to periods of a decade with particular implications for infrastructure planning, agriculture and human health, and extremes in variability that can trigger natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes, fires and so on (IPCC 2007). Furthermore, local studies of adaptation make it increasingly clear that while international and national policy makers may seek a clear measurement of impacts and adaptation associated with climate change – the incremental costs of mitigating or adapting to climate change, as the Global Environmental Facility puts it (Labbate, 2008) – on the ground, any meaningful measurement of adaptation needs to accept climate change is contextualised with the other risks (social, economic and political as well as environmental) that shape and limit human well being and the functioning of socio-ecological systems (Pelling and Wisner, 2009). This is the difference between an economic analysis of the farming sector of a country, and understanding the competing choices that shape adaptive capacity and actions for an individual farmer put in the context of the markets and regulatory regimes within which the farmer operates. Both are useful but partial lenses. The overlapping of seasonal and other climatic cycles with variation in baseline climate change and extremes makes it very difficult for specific events to separate out climate change signals from background weather patterns. Both short-term uncertainty in variability and extremes and long-term trends need to be considered (Adger and Brooks, 2003).

Initial work on assessing who or what adapts came from the assessment of regional or national scale agro-economic systems. For example, Krankina

et al.

(1997) refer to boreal forestry management strategies as a means of assisting forests adapt. Here the system of interest was ecological and the management system an intervening variable between it and climate change. This kind of work complements well the scale of resolution available from climate modelling and the existing understanding of ecological adaptation within agricultural sciences, but is less suited to explore well the social processes driving and limiting adaptive decision-making. Economic assessment has also operated well at this scale, seeking to identify the costs (and benefits) of climate change scenarios for agricultural systems and to varying extents factoring in human adaptation. In a review of the economics of climate change literature, Stanton

et al

. (2008) observe the narrow framing used to approach decision making for climate change policy. Harvey (2010) goes further, arguing that a new macro-economic vision is needed to help move past the internal contradiction of contemporary economics that promotes energy intensive growth and so accelerates climate change with consequent growth inhibiting outcomes. Contemporary incentives push for greater and greater economic growth in an attempt to grow our way out of climate change and its attendant risks. The extraction and concentration of wealth that results increases collective vulnerability while simultaneously accelerating climate change associated (and other environments) hazards.

More human-centred analyses have also flourished which seek to identify the human and social characteristics that determine the capacity of communities to face a shock or stress (Adger

et al

., 2005a). Local viewpoints help to contextualise adaptation within development and explain why people are unable or unwilling to take adaptive action (helping to identify the limits to climate change adaptation). From an analysis of two communities in Puerto Rico, Lopez-Marrero and Yarnal (2010) found that concerns for health conditions, family well being, economic factors and land tenure were given more priority by local actors than adaptation to climate change, despite their exposure to flooding and hurricanes. The results show the importance of addressing adaptation within the context of multiple risks, and of people’s general well being.

The diversity of work examining processes of adaptation has benefited from a number of typologies of adaptive action and their coherent synthesis, see Smit

et al.

(2000), Smit and Wandel (2006), Burton

et al.

(2007). Carter

et al.

(1994) distinguished between autonomous (automatic, spontaneous or passive adaptations) that occur as part of the routine of a social system, and planned (strategic or active) adaptations. Smit

et al.

(2000) also add that adaptations may occur unintentionally as an incidental outcome of other actions – further emphasising the importance of contextualising assessments of adaptive capacity and action. The timing of the adaptation relative to its stimulus has led to additional types. Some draw from the disasters community, which uses a staged model of actions for tracking behaviour before and after disasters. Burton

et al.

(1993) distinguish adaptations that prevent loss, spread loss, change use or activity, change location or engage in restoration. More generally, adaptations can be reactive, concurrent (especially important for analysis of adaptation to gradual and ongoing changes in climatic norms) and anticipatory. Adaptive actions can be long- or short-term, and this has come to be associated with a distinction between actions aiming for short-term stability (coping) or longer term change (adaptation) (see

Chapter 2

). Adaptation has also been characterised according to the form of action (technological, behavioural, financial, institutional or informational), the actor of interest (individual, collection), the scale of the actor (local, national, international) and social sector (government, civil society, private sector); and the costs and ease of implementation (Smit

et al.

, 2000). Maladaptation is used to describe those acts that, through bad planning or inadvertent consequences, cause either local or distant consequences that outweigh gains (Smit, 1993).