Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation (6 page)

Read Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation Online

Authors: Mark Pelling

Tags: #Development Studies

Adaptation is a deceptively simple concept. Its meaning appears straightforward: it describes a response to a perceived risk or opportunity. The IPCC defines climate change adaptation as ‘adjustments in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities’ (IPCC, 2008:869).

Complexity comes with distinguishing different adaptive actors (individuals, communities, economic sectors or nations, for example) and their interactions,

exploring why it is that specific assets or values are protected by some or expended by others in taking adaptive actions, and in communicating adaptation within contrasting epistemic communities. It is also important to distinguish between coping and adaptation, and adaptive capacity and adaptive action.

Coping precedes adaptation as a concept in explaining social responses to environmental stress and shock by some 30 years, and continues to be used within disaster studies to describe many of the same processes now captured by adaptation in the climate change community. The latter has to some extent re-invented the wheel in doing this (Schipper and Pelling, 2006). With these two terms in use, approaches have been taken to demarcate separate meanings. For some coping is associated with reversible and adaptation with irreversible changes in behaviour (White

et al.

, 2004). However, work on both adaptation and coping accepts that the transition from reversible to irreversible changes is critical for measuring the collapse of system sustainability (Swift, 1989). In practice, coping and adaptation still exist as parallel concepts serving epistemic communities with different origins but very similar interests and conceptual frameworks (see below). This can be seen by the slowness with which IPCC included the term coping and ISDR the term adaptation in their respective glossaries (ISDR, 2004).

Here adaptation is defined as: the process through which an actor is able to reflect upon and enact change in those practices and underlying institutions that generate root and proximate causes of risk, frame capacity to cope and further rounds of adaptation to climate change. Coping with climate change is defined as: the process through which established practices and underlying institutions are marshalled when confronted by the impacts of climate change.

Adaptation includes both adaptive capacity and adaptive action as subcategories. Capacity drives scope for action, which in turn can foster or hinder future capacity to act. This is most keenly seen when adaptation requires the selling of productive assets (tools, cattle, property) thus limiting capacity for future adaptive action and recovery.

Adaptive capacity has been conceptualised both as a component of vulnerability and as its inverse, declining as vulnerability increases (Cutter

et al.

, 2008). This distinction is important in designing methods for the measurement of adaptive capacity and vulnerability, which are generally conceived of as static attributes, and the subsequent targeting of investments to reduce risk. The distinction is less important for theoretical work and methods aimed at revealing vulnerability or adaptive capacity as dynamic qualities of social actors in history. For these projects more important is the recognition that vulnerability and adaptation interact and influence each other over time, shaped by flows of power, information and assets between actors. The relationship between vulnerability and adaptive capacity varies according to size and type of hazard risk and the position of the social unit under analysis within wider socio-ecological systems. Position matters as vulnerability and adaptive capacity at one scale can have profound and sometimes hidden implications for other scales. For example, a family in Barbados may benefit from living in a hurricane-proof house (low micro-vulnerability) but still be impacted by macro-economic losses should

tourists be deterred by hurricane risk in an island whose economy specialises in tourism with limited diversity (low macro-adaptive capacity).

The predominant understanding of adaptation is that while it is a distinct concept it is part of the wider notion of vulnerability. The IPCC conceptualises vulnerability as an outcome of susceptibility, exposure and adaptive capacity for any given hazard (and inadvertently compounds the definition through use of the term ‘to cope’!):

Vulnerability is the degree to which a system is susceptible to, and unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change, including climate variability and extremes. Vulnerability is a function of the character, magnitude, and rate of climate change and variation to which a system is exposed, its sensitivity, and its adaptive capacity. (IPCC, 2008:883)

Exposure is usually indicated by geographical and temporal proximity to a hazard with susceptibility referring to the propensity for an exposed unit to suffer harm. Adaptation then can either reduce exposure or susceptibility. Adaptive actions to reduce exposure focus on improving ways of containing physical hazard (building sea walls, river embankments, reservoirs and so on); they can also include actions to shield an asset at risk from physical hazard (by seasonal or permanent relocation or strengthening the physical fabric of a building, infrastructure and so on). There is some contention here with individual studies including shielding under exposure or susceptibility. However, this is only problematic when assumptions are not made clear, preventing aggregation of findings (a specific concern for the IPCC which seeks to build knowledge on vulnerability and adaptation from local studies worldwide). Susceptibility can be reduced by a wide range of possible actions including those taken before and after a climate-change-related impact has been felt.

The separation of mitigation and adaptation by the UNFCCC may help international policy formulation, but it is intellectually problematic. Mitigation can most logically be viewed not as a separate domain but as a subset of adaptation. It is an adaptive act aimed at ameliorating or reversing the root causes of the anthropocentric forcing processes behind climate change. Changing lifestyles and technologies to reduce carbon are then acts of adaptation targeted at supporting mitigation. Bridges between adaptation and mitigation are being made. Already the need to consider mitigation when developing adaptation strategy is recognised by the engineering community in the concept of climate proofing (McEvoy

et al.

, 2006). The analysis presented in this book does not include mitigation acts or policy, but does include discussion on the cultural and social norms that shape development worldviews and acts; a line of analysis that is well suited to questions of mitigation and in this way offers an approach that can be developed to connect mitigation to the adaptation agenda.

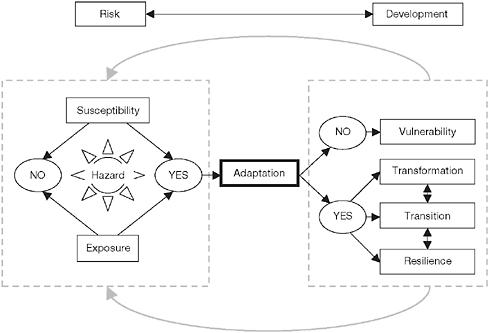

Adaptation occupies a pivotal position in the coproduction of risk and development (see

Figure 2.1

). Through this one phenomenon one can gain insight

into the social mechanisms leading to the distribution of winners and losers and identify opportunities and barriers to change as both risk and development coevolve. Too often, though, research and policy development on adaptation has focused on narrow technical or managerial concerns; for example, in determining water management or sea-defence and building structural guidelines. Wider questions of political regime form, social values and so on that direct technological and social development and risk have been acknowledged as root causes, but put in the background as too intangible or beyond the scope for adaptation work (Adger

et al.

, 2009c). Within the community of social researchers tackling climate change the social root causes are well acknowledged and amongst many policy-makers they are recognised too. Multilateral development agencies and NGOs such as WRI, WWF, Practical Action and CARE are taking a lead and tools are being developed to help policy-makers, who have understood the complexity of the problem but not had access to the tools to begin planning for adaptation.

The possibility that adaptation can inform political as well as managerial and technical discourses and structures is presented in

Figure 2.1

as a distinction between resilience, transition and transformation. Resilience (see

Chapter 3

) refers to a refinement of actions to improve performance without changing guiding assumptions or the questioning of established routines. This could include the application of resilient building practices or application of new seed varieties. Transition (see

Chapter 4

) refers to incremental changes made through the assertion of pre-existing unclaimed rights. This might include a citizens’ group

Figure 2.1

Adaptation intervenes in the coproduction of risk and development

claiming rights under existing legislation to lobby against a development that would undermine ecological integrity and local adaptive capacity. Transition implies a reflection on development goals and how problems are framed (priorities, include new aspects, change boundaries of system analysis) and assumptions of how goals can be achieved. Transformation (see

Chapter 5

) refers to irreversible regime change. It builds on the recognition that paradigms and structural constraints impede widespread and deep social reform; for example, in international trade regimes or the individual values that are constitutive of global and local production and consumption systems. Where adaptation is not undertaken in response to a perceived risk (a hazard event for which a social actor is both exposed and susceptible) vulnerability will remain unchallenged.

The three levels of adaptation are nested and compounding. Nesting allows higher-order change to facilitate lower-order change so that transformative change in a social system could open scope for local transitions and resilience. Compounding reflects the potential for lower-order changes to stimulate or hinder higher-order change. Building resilience can provoke reflection and be upscaled with consequent changes across a management regime, enabling transitional and potentially transformative change – but it could also slow down more profound change as incremental adjustments offset immediate risks while the system itself moves ever closer to a critical threshold for collapse. On the ground mosaics of adaptation are generated from the outcomes of overlapping efforts to build (and resist) resilience, transition, local transformative change and remaining unmet vulnerabilities; mosaics that can change over time as underlying hazards and vulnerabilities as well as adaptive capacity and action change driven by local and top-down pressures.

The discussion of terms so far has been generic with climate change leading potentially to opportunities as well as threats. On the ground opportunities arise for some actors from even the most catastrophic of climate change associated events. This is especially so when accountability and transparency are limited, as they are post-disaster creating gross market distortions: following Hurricane Katrina, a contracting company Shaw charged FEMA US$175 a square foot for temporary roof repairs, material costs were provided by the USA government and workers paid as little as US$2 a square foot (Klein, 2007). Elsewhere increased rainfall and temperatures may extend the growing season, leading to locally increased agricultural productivity, particularly in developed countries that can also capitalise on technological innovation leading to local benefit but further global inequality (UNDP, 2007). There may be more benign opportunities from climate change that need not contribute to greenhouse gas emissions or exaggerate social inequality (such as crop reselection), but these appear trivial compared to present and predicted costs. The annual impact from natural disasters associated with climate change alone accounts for tens of thousands of deaths, millions of people affected and billions of US$ lost, with drought, flooding, temperature shocks and wind storms causing the greatest impacts (Guha-Sapir

et al.

, 2004). By 2080 the number of additional people at risk of hunger could reach 600 million (Hansen, 2007). Climate change threatens the Millennium

Development Goals and most especially the development prospects of a large section of humanity. UNDP (2007) argues that some 40 per cent of the world’s population, over 2.6 billion people, will be consigned to a future of reduced opportunity without action to mitigate and adapt to climate change. With this context, our focus on adaptation is primarily as a mechanism to avoid harm.

The impacts of climate change will be felt directly (weather related and sea-level rise events), indirectly (through the knock-on consequences of reduced access to basic needs as critical infrastructure is damaged or employment lost) and as systems perturbations (the local implications of impacts on global commodity prices or international migration). Adaptation therefore needs to insert itself to ameliorate vulnerability caused by each level of impact. However, as one moves from direct through indirect to systems perturbations, climate change impacts interact with other systems features such as development policy, demography and cultural norms. This makes it increasingly hard to identify and communicate the consequences of climate change in isolation so that adaptation becomes both a climate change specific and more generic human process of development. The vastness of climate change and the multitude of pathways through which it can affect life and wellbeing for any individual or organisation make it almost impossible for ‘climate change’ in a holistic sense to be the target of adaptation. In comparison, international targets for mitigation are relatively simple. Rather, people and agencies tend to adapt to local expressions of climate change – flood events, changing crop yields or disease vector ecologies, often without attributing impacts or adaptation to climate change. This again makes identification, communication and ultimately the development of supporting governance structures for climate change adaptation a challenge unless such efforts are integrated into everyday activities and structures of policy-making.