Adrift (12 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

It's hard to tell when men are remembering things as they were and when they have innocently constructed or elaborated on memories. But every now and then the Geezer would surprise the skeptical. You might get a glimpse of an old newspaper clipping titled, "Local Lobsterman G. Bracy Roller-skates down Cadillac," or spy an old photo of a barnstorming acrobat clothed only in a baggy jumpsuit, with the caption, "Calls himself the Batman." Who is to say what is not true and what is not possible?

Ship ho! I glance up and there she is, close by, a sweetly lined red-hulled freighter with white whale strake and shapely bow slicing her way right for me. It's incredible that I haven't seen her sooner. They must have spotted the raft and are headed over to check it out. I load the flare pistol to satisfy their curiosity. As it shoots skyward and pops, the vessel cuts the distance between us at twelve to fourteen knots. The flare isn't as bright as it would be at night, but the crew can't miss its smoke and flame hanging in the air. If anyone is looking, it is impossible for him not to see me. The raft isn't disappearing into any troughs, and I have the full ship continually in view. I light an orange smoke flare that hisses and wafts a tawny genie downwind, close to the water. My eyes search the bridge and deck for signs of life. The ship is now so close that if a deckhand scurries into view I will be able to tell what he is wearing. But the only thing moving is the ship itself. I pull in the man-overboard pole, extend it high over my head, and wave frantically. I shriek above the soft murmur of the raft gliding over the water, the shush of the ship's bow wave, and the beat of her engine. "Yeoh! Here! Here! Bloody hell can't you see!" I yell as loud as I can until my throat cracks. I know that my voice must be drowned out by shipboard clamor. Still, it is a relief to break the silence. She steams on. Such a lovely ship ... too bad. Within twenty minutes she has disappeared over the horizon.

How many others can possibly pass so close? Most likely none. How many will pass that I will not see? How many won't see me? In this century there are few eyes aboard ships. In heavily traveled sea lanes, where collison is an immediate threat, a good watch is kept. Navy ships also have the manpower and the desire to keep a constant lookout. But in the open ocean, the captain of a merchant ship may keep only one of his few crew on the bridge to take a cursory glance about the horizon every now and then.

Maybe

there's an eye on the radar.

Maybe

the VHF radio is flipped on to channel 16 while the vessel charges blindly over the ocean under the automatic pilot's command. And even if there is a watch, after seeing that no ships are in view he turns his attention back to his novel or girly magazine, or he steps out onto the bridge to take a smoke in the shade. My raft would be hard to spot even if a ship had been notified. A 250-foot red freighter didn't appear to my eyes until it was almost upon me. What chance does my bubble have of being seen? Perhaps I should stay awake at night when flares are most effective. But I must stay awake in the day to properly tend the still. And a good watch at night would cut my precious water supply. I try to calm my frustrations by repeating, "You are doing the best you can. You can only do the best you can." One thing is clear. I cannot rely on others to save me. I must save myself.

The freedom of the sea lures men, yet freedom does not come free. Its cost is the loss of the security of life on land. When a storm is brewing, the sailor cannot simply park his ship and walk away from it. He cannot hide within stone walls until the whole thing blows over. There is no freedom from nature, the power that binds even the dead together. Sailors are exposed to nature's beauty and her ugliness more intensely than most men ashore. I have chosen the sailor's life to escape society's restrictions and I have sacrificed its protection. I have chosen freedom and have paid the price.

The last wisp of smoke lies faint on the horizon where the ship disappeared. Despite my rationalization, I am bitterly disappointed. I am not angry, but I am ready to be enslaved by shoreside life for a while. Words of

The Old Man and the Sea

come to me. "If only the boy were here ... if only the boy." I need a rest, another set of eyes, the companionship of another voice. But even a companion would not improve my chances. There would not be enough water for two of us.

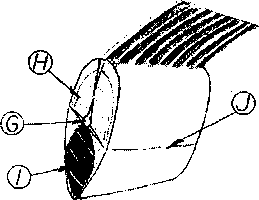

Perhaps flying a kite will increase my visibility. I cut a swatch from the space blanket and make a diamond-shaped bird, using a couple of battens from the piece of mains'l as a cross frame. It's pretty heavy for its size and needs a tail. I can't get it to fly from the raft, but maybe I can perfect it by the time I get to the shipping lanes. It is quite effective as a water gutter. I tie it up to the back of the tent, where it catches most of the spray that dribbles through the observation port. A proper kite would be a valuable piece of emergency equipment, a bright beacon flying hundreds of feet above the ocean, but mine is destined to assist in keeping things dry, which helps me heal.

Again the sun sets, the fish attack. I pump up the raft's slowly deflating tubes, eat my fish sticks, search for rest and find only sleep. Again in the night a shark comes. It rips across the bottom with astounding speed and tears me from comfortable fantasy. As it scrapes under a second time, I strain to detect its form in the depths but cannot. It is gone, and for another windless night the raft flops and awaits the final attack.

Until now I have referred to my raft simply as "the raft." I decide that it must have a name. I have owned two inflatable dinghies in the past, and I jokingly named them

Rubber Ducky I

and

Rubber Ducky II.

It only makes sense to continue the tradition. Therefore, I dub thee

Rubber Ducky III.

In the morning I crawl around on top of

Rubber Ducky,

sliding my hands over the rubber, feeling for signs of deterioration. The bottom feels good, at least as far under as I can reach, but there are several divots in the bottom tube around the gas cylinder. Perhaps they've been there all along, or perhaps a shark has been chewing on my raft. The gas cylinder hanging under the raft still worries me, but I can't think of anything to do about it.

Above the water, the tubes are beginning to road-map with cracks from the baking sun. The exterior handline is so tight in spots that it chafes on the tubes. When the raft was tied to

Sob,

the force from the sea's attack must have yanked it through the anchoring points. With all my might, I try to loosen and readjust it, with no effect. The orange-pigmented waterproofing of the canopy has been bleached, beaten, and washed off. It no longer keeps water out of the raft, and any rainwater picks up small orange particles. Trying to swallow it is like forcing down another man's vomit. If I could have effectively collected water from the past showers, I'd be about six pints richer. I curse it. Robertson says that one can absorb up to a pint of undrinkable fresh water by enema, but I have no way to give myself one.

The sun rises and the bake-off begins again. My past continues its procession before my mind's eye. There is no freedom to get on with my future. I am not dying and I am not finding salvation. I am in limbo.

In my mind, a cool stream winds through tall verdant trees. I look into the bubbling water as it tumbles over a rocky bottom. The smell of fresh biscuits wound around sticks, browning over a campfire, fills my nostrils. It is really just the smell of drying fish.

I see a majestic harbor full of yachts.

Solo

is there. The ragged volcanic peaks of Madeira rise in my mind. Eons ago they grew from the sea bottom and blasted out upon the surface. Catherine and I ride the bus that rattles its way around the torn precipices, on cobbled, snaking roadways carved into the vertical slopes. Villages that are a few miles apart by air are an hour apart by road. A gentle toss will carry a stone thousands of feet down. It takes eight hours to drive thirty miles. Lush, terraced fields stretch from oceanside valleys up the slopes until they reach vertical rock. Farmers harvest grapes, for famous Madeira wine, bananas, and other fruits of every variety, including some found only on this mystical isle. We investigate a village perched high upon a ridge over the sea. Melodies from Catherine's flute intertwine with a northerly breeze that sweeps up the slopes, bringing with it the music of crashing surf. Elegant peaks, soft valleys, and tranquil people combine in a fairy tale setting.

It is Sunday. There is no electricity. No TV football, no video games. The people of the village line the street, occasionally shifting positions with their neighbors to gossip or simply to look on while life passes by. The island's natural wealth allows this tranquility. Water springs everywhere. I want a beer, "

Aberto, senhor?

" He is not supposed to be open, but we are special. The ' bar is the basement of an ancient house. Its damp rock walls cool us. A tap pokes out from one wall. A large wooden cask sits dimly lit in the back. Spiced tomato sauce filled with tender beef boils atop a corner stove. The man gives us beer and fills glasses with wine from the cask. It's new wine from his vineyard. He hands me a sandwich of the spiced meat, too. He welcomes us into his life as if we are old friends, but we do not stay. I must get on to the Canaries.

We originally planned a two-week voyage, but winds have been light. Catherine and I have been together for over a month. She is a good crew, eager to learn, but she expects more. She expects all men to love her. It is an odd turnabout from the usual female complaint: "All my captain wants to do is get me into the sack." To Catherine I am aloof and silent. "You are a hard man," she continually tells me.

It is probably true. Most of the women I've been close to have been very liberated types. I have always respected that, but in turn I've demanded much from them. I have demanded that I should not be subjected to female chauvinism, that I should not be duty bound to do all of the "man's work." So when Catherine has been on watch and a jib or pole has fouled and she has implored me for help, I have snapped at her, "When it is your watch,

you

deal with it!" But I know that my hardness is more than this. My impatience and unkindness stem from deeper roots. Seven years of marriage ending in divorceâand an ensuing hot relationship that left me singedâhave made me tired of the traumas of women and of love. Perhaps it is a fear that I am unwilling to face. Perhaps I have traded my quest for love for the quest to finish what I set out to do. I don't really know, but these are among the secrets that I'm unwilling to share with Catherine, despite her soft French voice and lovable smiles. I only want to sail, write, and draw. If anything, as our voyage lengthens, the more she tries to soften me up, the harder I become. I want my boat back to myself. As if I am afraid of the magic that the tranquility of Madeira is spinning, I set sail after only three days. Was I wrong? Safe harbors ... that is what I want

now.

Why did I push on? Why did I not allow myself to soften?

I'm determined to taste campfire biscuits again, to feel cool streams; I will build another ship and give myself another chance to feel the warmth of human passion. I do not think "if I get home" but only "when I get home."

I was foolish to let those dorados escape. The butcher shop is bare. My stomach churns and growls in anguish. I hunt my companions for days on end. I begin to recognize many. One still trails a fishing line from its mouth, another has a torn fin, another a large gash in its back that is slowly scarring over. There are differences in size and slight variations in color. The females differ markedly from the males. They are slimmer, smaller, with more rounded foreheads. I often see two very distinctive bright green fish that never approach closely. The female is over four feet long, the male even bigger. Dorados up to six feet long, weighing sixty pounds, have been recorded. The emerald elders are as wary of me as I am of them. The youngsters ignore their warnings and come close to the raft, still cautious. They know where I can shoot, and they avoid these areas or sneak by when I'm not looking. They slowly swim into range and then dart this way or that. These fish are not stupid, and they can swim at fifty knots, making them the fastest fish alive. The emerald elders leap yards through the air and land with a thunderous slap. I would not be surprised to see them suddenly take off in flight. It is as if their play is a statement to me: "Behold the magnificence that our race can attain." Yet these fish are modest creatures. They say nothing and swim on.