Adrift (9 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

My onboard still is a dismal failure. The evaporation rate is much too slow and the system too ventilated to allow condensation on the box lid. At least I get the last still to work by tying it close to the raft so that it isn't flung about by waves; however, it chafes there. Why not try it aboard the raft? I pull it up onto the edge of the top tube and tie it in place. The balloon sags a little, but it stays put and the wick isn't touching the plastic. Drainage of the distilled water is also improved, because the distillate collection bag hangs down rather than trailing out horizontally. I watch as pure, clear, unsalted drops begin to collect and drain into the bag. I have her working! And I have three pints of reserve ... possibly I can make it! After eleven days, I have renewed hope. As long as the raft holds together and the still functions, I can last another twenty days. The raft ... Please, no sharks. I am not only worried about their rows of jagged teeth. Their skins are like coarse sandpaper; they can rip my raft apart just by rubbing against it.

I lie back in the healing heat of the sun. There is an abundance of time, a bumper crop of it, in which to think. Dorados and triggerfish nudge the rafts bottom. Baby gooseneck barnacles have begun to flourish on it. The triggers feed on them. I don't know why the dorados are bumping. They begin in the evenings, at about dusk, firmly nudging wherever I or my equipment push into the floor. It is as if they were dogs pushing their begging heads under a human hand for a piece of meat, a scratch behind the ear, or a playmate. I call them my little doggies or doggie heads. The triggers I call butlers. They have that starched-collar look.

The sea lies flat. Clouds sit motionless in the sky as if glued there. The sun beats down, roasting my arid body. The working still may provide just enough water to carry me the three hundred miles to the shipping lanes. The wind has turned. The lanes somehow always seem to be three hundred miles away. As I succumb to drowsiness, fantasies of being picked up by a ship and lying in the cool green grass by the pond at my parents' house race through my head.

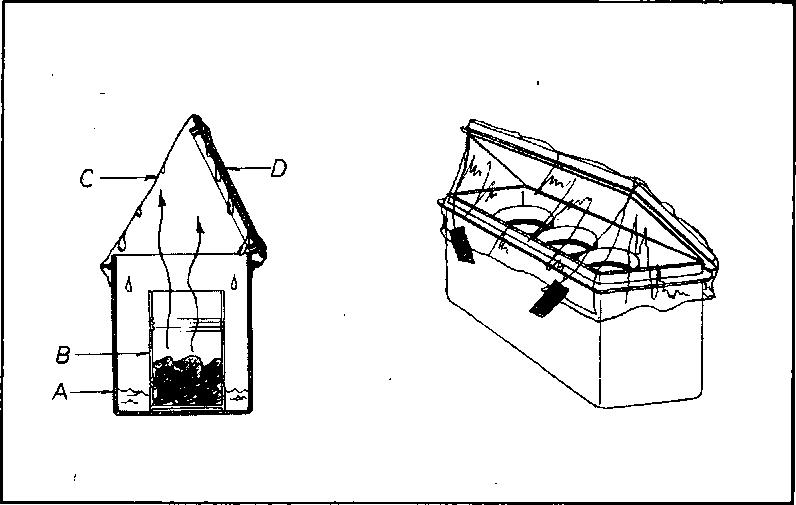

I attempt to make an onboard solar still. Perspective view,

right.

Section,

left:

(A) The Tuppeware box. (B) I place three empty water cans in the box. In each I crumple black cloth from the solar still that I cut up and wet it with seawater. The cloth should soak up more heat and give more surface area for evaporation than seawater simply floating in the cans. Theoretically, fresh water vapor should rise and collect on the plastic tent that I've taped over the front and ends (C) as well as the box lid (D), and then drip down the sides and collect in the box bottom around the outside of the cans. The experiment is a depressing failure. I don't have enough tape to seal the tent to the box thoroughly, and the tape does not stick well to the slippery box. Therefore, excessive ventilation on the inside of the tent prevents moisture from collecting.

The shaking of the raft jerks me from my stupor. I look down. A flat, gray, round-headed beast scrapes its hide across the bottom as it lazily swings around for another bite. It's incredible that the dorados and triggers have not fled the shark at all! Instead, they collect closely around it. I think they have invited him for tea. "Come over to our place and have a taste of this big black crumpet." He slowly swims around to the stern and slides under. Rolling over, belly up, he bites one of the ballast pockets, quaking the raft with his convulsive ten-foot torso. Bless the pockets. He might tear a hole in the floor, but that shouldn't damage the tubes, at least not yet. Should I take a shot and risk losing the spear? He cruises out in front of me just below the surface. I thrust, and the steel strikes his back. It is like hitting stone. With one quick stroke he slithers away, not in any particular hurry. I watch for a long time before collapsing, craving water more than ever.

I thought that the fish would scatter and give me notice of a shark's approach, but now I know that I cannot trust them to warn me of danger. I worry about the gas bottle and line that inflated the raft and that lie under the bottom tube. If that line is bitten through, will the whole raft deflate? Will the bottle lure the sharks to bite into the tube from which it hangs? Worry, worry, worry. It is apprehension that beds with me each night and apprehension that awakens me each day. As darkness comes and I drift off to sleep, I long to be in a place with no anxieties. How repetitious and simple my desires have become.

The raft is lifted and thrown to the side as if kicked by a giant's boot. A shark's raking skin scrapes a squeak from it as I leap from slumber. "Keep off the bottom!" I yell at myself as I pull the cushion and sleeping bag close to the opening. I perch as lightly as possible upon it. Peering into the night, I grasp the spear gun. He's on the other side. I must wait until he comes to the opening. A fin breaks the water in a quick swirl of phosphorescent fire and darts behind the raft, circling in to strike again. A flicker of light in the black sea shows me he is below, and I jab with a splash. Nothing. Damn! The splash may entice him to attack more viciously. Again the fin cuts the surface. The shark smashes into the raft with a rasping blow. I strike at the flicker. Hit! The water erupts, the dark fin shoots out and around and then is gone. Where is he? My heart's pounding breaks the silence. It beats across the still black waters to the stars. I wait.

Gulping a half pint of water, I rearrange my bed so that at the first bump I can be ready at the entrance. Hours pass before I drift again into uneasy sleep.

For two days the going is slow under the baking sky. I go fourteen or fifteen miles each twenty-four hours. Hunger wrenches my insides. My mouth burns. But the still produces twenty ounces of water a day. I begin to rebuild my stock while drinking one pint for each arc of the sun. The calm is also good for visibility. Should a ship pass, the glowing orange canopy will be more easily spotted. However, sharks also visit more frequently in calm weather. The shipping lanes lie over two weeks to the west at this pace. For hours I pore over the chart, estimating minimum and maximum time and distance to rescue.

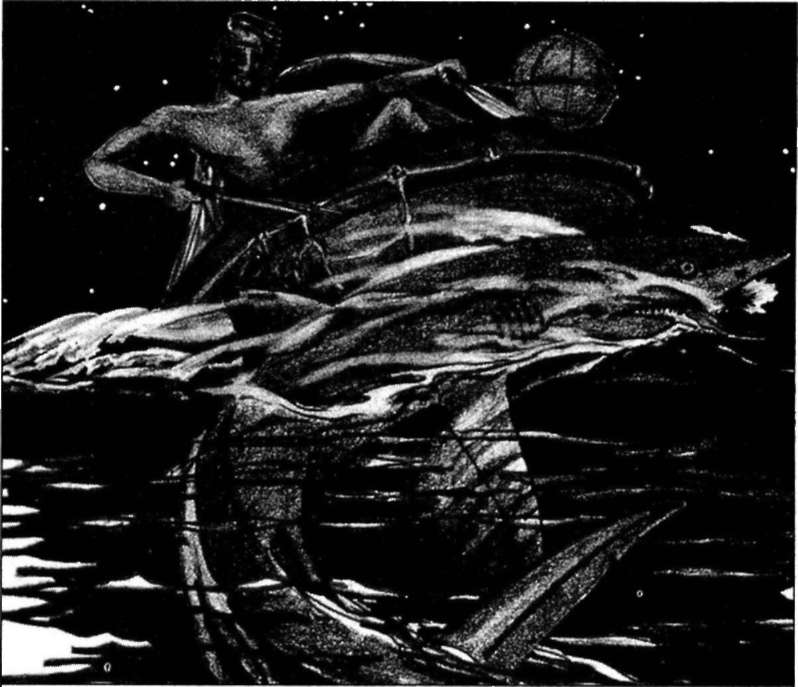

My heart's pounding beats across the still black waters to the stars.

In my thirteen days adrift, I have eaten only three pounds of food. My stomach is in knots, but starvation is more subtle than simply increasing pain. My movements are slower, more fatiguing. The fat is gone. Now my muscles feed on themselves. Visions of food snap at me like whips. I feel little else.

Several triggerfish swim up from astern as the breeze builds. They come up broadside. Once again I aim and fire. The spear strikes and drives through. I yank the impaled fish aboard. Its tight round mouth belches a clicking croak. Its eyes roll wildly. The stiff, rough body can only flap its fins in protest. Food! Lowering my head I chant, "Food, I have food." Shrinkage of the codline around the cutting board has warped a trough into it. I wedge the trigger under the line in the trough and try to strike it unconscious with my flare gun. It's like clubbing concrete. Powerful thrusts with my knife finally penetrate the trigger's armored skin. Its eyes flash, its fins frantically wave about, its throat cracks, and finally it is dead. My eyes fill with tears. I weep for my fish, for me, for the state of my desperation. Then I feed on its bitter meat.

M

Y TRIGGERFISH

proves to resemble a rhinoceros more than a butler. A thick, horny bone protrudes from its back. I pound on the handle butt of my sharp sheath knife, finally driving the point through the skin, which is as tough as cowhide and has a very rough coating that looks like ground-up glass.

FEBRUARY 17

DAY 13

I bury my face in the raw, wet flesh to suck up the brownish-red blood. Intense, revolting bitterness fills my mouth, and I spit it out. Hesitantly, I take an eye into my mouth, crush it between my teeth, and retch. No wonder even sharks steer clear of this fish.

Because of its tough hide, the little ocean rhino must be cleaned from the outside inâskinned, filleted, and finally gutted. My teeth tear at one, bitter, stringy fillet, tough as the proverbial boot, and I hang the other up to dry. Organ meats, especially the liver, are the only palatable morsels to be found. I think of a movie character who is a cranky, miserable old fart at the beginning, but who is finally understood and loved in the end. I have penetrated the distasteful, tough facade of the trig-gerfish to discover a savory richness in its inner being.

Once when I was a small boy in Massachusetts, a hurricane tore across the land. I remember thick oak trees waving about in the wind like blades of grass. My brother had built a sturdy treehouse high atop the limbs of one tree. The storm blew it to pieces. The power of that storm was awesome, but I had heard of stronger forces, atomic forces, that eclipsed such storms. I put five dollars, a jackknife, fishing reel, and associated paraphernalia into a box and secreted it in my desk drawer. If disaster struck, I would be ready. If anyone survived, it would be me. Such are the immortal fantasies of youth.

The small amount of food is little comfort to my bones, which are beginning to protrude from my atrophied muscles. Worse is a deep emptiness in my soul. I'm an ill-adapted intruder in this domain, and I have murdered one of its citizens. Death may be thrust upon me more quickly, more unexpectedly, even more naturally than it came to this fish. My weak physical and frightened emotional selves fear this. My strong rational self acknowledges that it would be simple justice. As I swallow the sweet liver, I search for a savior across the deserted waves. I am quite alone.

The gray overcast sky reflects a calm, bleak sea. Yesterday's sun allowed the solar still to conjure up twenty ounces of fresh water. Its magic will be less potent today. Clouds ease the roasting afternoon sun but deny me maximum water production. Life is full of paradoxes. When the wind blows hard, I move well toward my destination, but I am wet, cold, scared, and in danger of capsizing. When it is calm, I dry out, heal, and fish more easily, but my projected journey lengthens and my encounters with sharks increase. There are no good conditions in a life raft, and no comfortable positions in which to rest. There are only the bad and the worse, the uncomfortable and the less so.

Quick, hard punches batter my back and legs. It is not a shark, but a dorado. I am not surprised. Their nudging has grown more confident, almost violent, like a boxer's jab. Time and again they hit where any weight indents the floor of the raft. Perhaps they are feeding on barnacles. The projection makes it easy for them to get at the little nubs of barnacle meat that have begun to grow under me.

I have missed my targets so many times that I am slow to take aim. Punch, punchâit's a damned nuisance. The dorados circle in from ahead and take a wide sweep around the raft as if in a bombing pattern. I cannot stand up to watch their final approach and simultaneously ready myself with the spear, so I kneel, awaiting my chance to strike. They shoot out in front, to the sideâtoo wide, too deep.

Casually I point the gun in the general direction of a swimming body. "Take that!" Thump. The fish lies stunned in the water. I too am stunned. I hoist him aboard. Foam, water, and blood erupt about his flailing tail. His clublike head twists spasmodically. All my strength goes into keeping the spear tip from ripping into my inflated ship as his heavy, thrashing body whips it about. I leap upon him and pin his head down onto the eighth-inch-thick plywood square that serves as my cutting board. A big round eye stares into mine. I feel his pain. The book says press the eyes to paralyze the fish. My captive's fury increases. Hesitantly I plunge my knife into the socketâeven more fury. He's thrusting loose. Watch the spear tip. There is no time for sympathy. I fumble with my knife, stick it into his side, work it about, find the spine and crack it apart. His body quivers; his gaze dulls with death. I fall back; behold my catch. His body is no longer blue as when in the sea. Instead, my treasure has turned to silver.