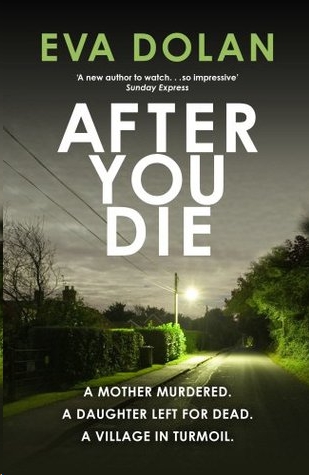

After You Die

Contents

Dawn Prentice was already known to the Peterborough Hate Crimes Unit.

The previous summer she had logged a number of calls detailing the harassment she and her severely disabled teenage daughter were undergoing. Now she is dead – stabbed to death whilst Holly Prentice has been left to starve upstairs. DS Ferreira, only recently back serving on the force after being severely injured in the line of duty, had met with Dawn that summer. Was she negligent in not taking Dawn’s accusations more seriously? Did the murderer even know that Holly was helpless upstairs while her mother bled to death?

Whilst Ferreira battles her demons, determined to prove she’s up to the frontline, DI Zigic is drawn into conflict with an official seemingly resolved to hide the truth about one of his main suspects. Can either officer unpick the truth about mother and daughter, and bring their killer to justice?

Eva Dolan is an Essex-based copywriter and intermittently successful poker player. Shortlisted for the Crime Writers’ Association Dagger for unpublished authors when she was just a teenager, her début novel

Long Way Home

, the start of a major new crime series starring two detectives from the Peterborough Hate Crimes Unit, was published in 2014 to widespread critical acclaim.

Long Way Home

Tell No Tales

‘I’m not scared.’

Nathan repeated it under his breath as he walked, focused on the words, using them to block out all the worse ones buzzing around in his head. The loud and terrifying ones which wouldn’t leave him, the begging and pleading and swearing.

He heard the scream, the sound of her body falling to the floor.

‘I’m not scared.’

A car passed him in a surge of engine roar and aggressive bass, moving so fast that its slipstream tugged at his clothes. He looked up from his feet, watched it disappear as the road dipped, brake lights blinking.

It would be easy to walk out in front of the next vehicle that came. Wait for one of the big lorries that thundered along this road, heading down to the A1. He’d seen it happen on TV. A bang and everything went black.

‘I’m not scared.’

But he was. Too scared to do that, even though he knew it would mean an end to the voices and the danger. Even though everyone would be safe if he was gone.

Nathan kept walking along the hard shoulder, the grass bank rising steeply to the left, as high as a house, blocking out the final flare of the evening sun, casting a shadow deep enough to raise goosebumps on his bare arms and hide the bloodstains on his camo-print trainers.

A car slowed as it approached him and he tensed but kept moving, fighting the urge to turn, knowing not to make eye contact with the driver. If he did that there would be no escaping. They’d see what was wrong with him and then he’d never get away.

The window opened as the car drew up next to him, something rattling under the bonnet, and a woman’s voice asked:

‘Are you alright?’

He sneaked a glance out of the corner of his eye; a small red car, an old woman, grey-haired and posh-looking, with a fluffy white dog on the passenger seat.

‘Does your mother know you’re out?’ she asked.

The scream again, in his head.

‘I’m on me way home,’ he said.

It was a stupid lie. There were no houses here. Nothing but the road cutting between the steep and tangled banks, then the service station on the side of the A1 and the industrial estate beyond that.

‘You shouldn’t be out here on your own at this time of night,’ she said. ‘It isn’t safe for a boy your age.’

‘I’m okay.’

‘Why don’t I take you home?’ she said. ‘I’m sure your mother must be worried sick about you.’

He shook his head, felt his throat tightening, closing up around the words he barely managed to force out. ‘I live there.’

‘Where?’

He pointed across the road towards a gated farm track, still avoiding her eyes. ‘Down there.’

‘Alright. Well, be careful crossing the road, they drive like maniacs along here.’

She pulled away, but slowly and he realised she wasn’t going to leave while he was walking along the hard shoulder. She was probably already taking her mobile out, thinking about calling the police, telling them about the boy out walking alone in the middle of nowhere on a Saturday evening. Children didn’t do that here.

Nathan ran across the road, towards the metal gate, and when he saw it was padlocked climbed over it, scratching his arm on a branch from the hedge. There was a farmhouse ahead of him, barns and tractors, barking dogs.

He began to walk towards it, slow, shuffling steps, and when he’d walked far enough turned and double-backed, peeped around the hedge to check that the woman had gone.

He waited, hands shaking, for a few long minutes, in case she double-backed as well, and when he couldn’t wait any longer climbed over the gate again and started on towards the service station.

There was just enough light from the setting sun to make out where he was going – no street lights here – and he felt safer in the gloom, his tear-stained face and the blood on his trainers hidden.

‘I’m not scared.’

He tried not to think. He knew he couldn’t let the fear overwhelm him again.

The service station spread out in front of him, lit up bright and cheerful, people everywhere, coming out of the fast-food places and the hotel, couples and families, men and women on their way home. They would be like the lady in the car, asking questions, wanting to help him. The wrong kind of help.

Nathan made his way to the petrol station, skirting the main forecourt, and headed to the area where the lorries filled up, looking for one heading in the direction he needed to go. There were a few parked up for the night nearby and he thought it would be easy to cut a slit in the fabric side of one and slip inside, curl up and wait for morning.

Most of them had foreign writing on them, foreign number plates. He hadn’t planned for that. One was from Birmingham, a bakery. Not where he wanted to go but on the way.

As he turned the knife handle around in his pocket, willing himself to make the cut, a heavy hand came down on his shoulder and he flinched away, just managed to stop himself bringing the knife out.

‘What you doin’, son?’ The man was smiling and when Nathan didn’t answer, he cocked his head. ‘You speak English?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Thought you was a stowaway or something.’

‘No.’

‘What you doing hanging around here then? Waiting for your dad?’

‘I need a lift.’

The man looked him up and down and Nathan’s fingers tightened around the knife in his pocket, the perforated steel sticky against his skin. ‘Bit young to be hitch-hiking, aren’t you?’

‘I’m sixteen,’ Nathan said, adding five years on, praying the man would believe him.

He nodded. ‘And not from round this way, I reckon?’

‘No.’

The man pressed his key fob and the bakery lorry’s lights flashed as the doors unlocked. ‘You running away from home?’

‘I’m trying to get home,’ Nathan said.

‘Where’s that?’

‘Manchester.’

‘You don’t sound Manc.’

‘I am.’

The man sighed as he opened the driver’s-side door, paused with one foot on the step. ‘Alright then, young’un. Let’s get you home before you get yourself in trouble.’

Nathan walked around the lorry and found the passenger’s-side door open already, the man leaning across the seat, holding out his hand.

‘You get up alright on your own?’

Nathan hauled himself up and into the cab, smelling the bread in the back, but something else too, sharp and sour.

They’d been driving for a few minutes before the man spoke.

‘You’re not really sixteen, are you?’

‘I am.’

‘I’d say you’re more like eleven or twelve.’

Nathan gripped the hand rest. ‘I’m small for me age.’

‘Don’t worry, son, I’m not going to tell anyone.’ The man laughed and something about the sound put a cold lump in Nathan’s stomach. ‘It’ll be our little secret.’

Through the grimy window he watched fields smear by, the tops of houses gone in seconds, the village he’d left falling away behind them, so quickly that he wanted to shout for the man to stop, turn around, take him home. But it wasn’t his home, never had been and never could be. Not now.

‘I’m not scared.’

1

‘I’m not sure now,’ Anna said, standing in the doorway of the box room, one hand cupped under the bump showing through her tunic. ‘It’s very pink.’

Zigic stopped painting and stepped back from the wall, the ghosts of four darker shades still visible through the first coat of paint he’d put on, ragged patches half a metre square.

‘You liked it an hour ago,’ he said.

‘The light was different then.’

He suppressed a sigh of irritation.

They’d spent most of Saturday looking at colour charts, Anna placing them against the Cath Kidston fabric she’d already picked out for the curtains and the very specific ivory of the new cot he didn’t want to put together yet, sure they were tempting fate by getting the nursery ready when she was only six months gone. He told her to choose whatever colour she wanted, he was just the muscle, and after an exhaustive decision-making process they arrived at this one – Middleton Pink.

‘It didn’t look this bright in the tin,’ she said.

‘Paint always dries lighter.’

‘The first coat’s dry.’ She touched her hand to the wall, showed him her palm. ‘Look, completely dry.’

Zigic dropped the sheepskin roller into the tray, spattering paint across the dust sheets which still bore traces of the emulsion they’d used to decorate the nursery for Stefan in their old house. Five years ago now and seeing the spots and arcs of sky blue he felt a plunging sadness about how quickly the time had passed. He could still remember the red checked shirt Anna wore, knotted above her cumbersome stomach as she knelt down to do the skirting boards, Milan ‘helping’ her with a tiny brush. Didn’t remember the decor choices being such a nightmare then.

This was different though.

This was the little girl Anna had always wanted.

‘Do you want to change it?’ he asked.

She made a non-committal murmur, eyes moving around the room.

‘I don’t mind redoing it,’ he said. ‘But let’s decide now while it’s early enough to go out and buy something else, okay? I might not have another weekend off in a while.’