Agnes Strickland's Queens of England (20 page)

Read Agnes Strickland's Queens of England Online

Authors: 1796-1874 Agnes Strickland,1794-1875 Elizabeth Strickland,Rosalie Kaufman

Tags: #Queens -- Great Britain

One source of trouble to Catharine during the first year of her marriage was poverty. She did not receive half the amount that the marriage treaty allowed her, and was forced to practice the most rigid economy to avoid falling into debt. This she did so successfully that the financiers of the government could not help applauding her for it.

When she was ill one summer, her physician recommended the medicinal waters of Tunbridge Wells; but neither she nor her officers had any money to pay the expenses of such a trip, and it required at least two months before it could be raised.

Catharine of Braganza.

207

[A.D. 1^63.] Previous to Catharine's departure for the wells, she received the good news from her native land that she had eagerly hoped for. The combined troops of Portugal and England had defeated the Spanish army with great loss; and as the battle took place very near Lisbon, it had

THE ORATORY.

been desperately contested by the Portuguese, while the Queen of England awaited the result with breathless anxiety. Colonel Hunt commanded the English forces; and when he led them up a steep hill to attack the troops under

Don John of Austria, the Portuguese general *exclaniied in ecstasy : '* These heretics are better to us than all our saints! "

Queen Catharine was so ill the following autumn that it was universally believed she could not recover. The king repented of his unkindness when he thought she was going to die, and passed many hours at her bedside, bestowing the most loving attentions upon his sick wife, which had so good an effect that she recovered. Her convalescence was very slow, and almost before she was pronounced out of danger she was called upon to receive the French ambassador and another gentleman from the court of Louis XIV., who brought messages of condolence from that monarch on account of the royal lady's illness.

It seems cruel that Catharine should have been disturbed with such ceremonies before she was strong enough to endure them; but we must not forget that she lived in an age when privacy was a luxury unknown to royalty,

When she thought her death was at hand, she made her will, and gave orders for many domestic arrangements. Her only requests to the king were, " that her body might be sent to Portugal for interment in the tomb of her ancestors, and that he would remember the obligation into which he had entered, never to separate his interests from those of the king, her brother, and to continue his protection to her distressed people." Charles promised to obey; but by her recovery his wife spared him the test.

In the last reign we told all about the Roundheads, and the origin of their name. Of course theirs ceased to be the popular party when the Restoration took place; consequently, with a desire to avoid the sneers of the courtiers, they adopted wigs, which after awhile became so fashionable that even those whose long locks had been a subject of vanity to their possessors, had the folly to clip them off

and replace them with wigs or periwigs, as they were called. King Charles fell in with the prevailing style when he found himself growing gray, likewise the Duke of York, whose hair was far too beautiful to be concealed.

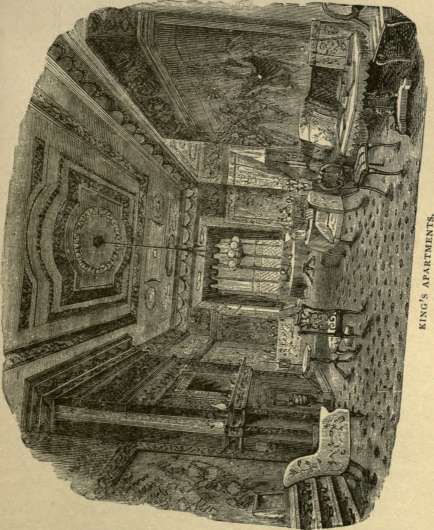

The necessity for economy that forced itself upon the queen soon begot for her the reputation of stinginess, though it was rather a matter of prudence than otherwise. She was obliged to save because she seldom received her full income. Fortunately, her tastes were simple compared with those of her royal spouse ; for while her bedroom furniture at Whitehall was of the plainest description, the only ornaments being sacred pictures and relics, the king's apartments were fitted up with all the extravagance and luxury of an Oriental nabob.

[A.D. 1664.] The summer after her recovery. Queen Catharine appeared in a silver lace gown, and walked through the park to St. James's Chapel, attended by her maids-of-honor, one bright, sunshiny morning, all in the same glittering material. Parasols had not then been introduced into England, so the courtly dames shaded their faces from the bright rays of the sun with gigantic green fans, — a Moorish fashion introduced by Catharine of Braganza at her court. Masks were often worn at that period to protect the complexion, but they were too warm in summer, and the shading fans were by far more comfortable. The trade with India, opened to the English by the queen's marriage treaty, filled the fancy shops with all sorts of gay and beautiful fans, which were put to another use besides that of sunshades. Ladies tpund them very convenient for screens when carrying on a little flirtation ; for a whispered conversation with a courtier behind one, or a bit of court scandal thus imparted, seemed improved by this spicy addition to the secrecy. Addison gives a pretty playful description of the use of the fan in several copies of the " Spec-

tator," with which the belles of the present day are no doubt familiar.

Trade with other countries had increased in England, and her merchants were anxious to push it still further; but Holland proved such a formidable rival in this matter that, notwithstanding the friendly relations that had so long existed between the two countries, Charles saw the necessity for preparing his navy for hostilities.

Lord Sandwich was ordered to sea, and Queen Catharine was so anxious to see the departure of the fleet that she and Queen Henrietta accompanied the king to Chatham for that purpose.

Shortly after this the Spanish ambassador aroused the queen's indignation by demanding the return of Tangier to his government. Of course Charles peremptorily refused; and the queen, out of a feeling of spite, pretended that she could not speak any language but Portuguese and French when addressed by that dignitary. As he knew only his native tongue, she thus spared herself the necessity of a prolonged conversation with her enemy.

Once, on the occasion of a launch at Woolwich, Catharine played her husband a sly trick. She went down from Whitehall with her ladies in her barge; but the water was so rough that they were all dreadfully sea-sick, excepting herself. The king, the Duke of York, the French ambassador, and the attendants went down in carriages by land. After the two parties met on ship>-board, a violent rain and hail-storm detained them for a long time. As soon as it abated, the queen stole ashore with her ladies, took possession of the carriages, in which they returned home; leaving all the gentlemen to make the best of a very rough trip by water.

[A.D. 1665.] The following year one of England's greatest naval victories was won by the fleet under the Duke of York's command.

The rejoicings occasioned thereby were cut short by the breaking out of the most terrible visitation of the plague ever known in England. Death, sorrow, and poverty spread from house to house, until the exceptions were those that did not bear a red cross in token of the existence of disease within. The queen-mother quitted the country, and, as the epidemic increased, the court was removed to Salisbury.

Many people attributed the plague to the appearance of a comet that had been observed a few months before. We of the present day laugh at such an absurd superstition; but in the seventeenth century a visit from one of those heavenly bodies was always contemplated with awe by the ignorant, who were unfortunately in the majority. King Charles was not of the number, for he had a taste for astronomy, and was delighted to have an opportunity of studying the comet in its different phases. For this purpose he spent several nights at the observatory at Greenwich, a building that he had founded, and Queen Catharine stayed with him twice until she saw the curiosity also. She was not gratified the first time, because astronomical calculations were not so accurate as they are at present.

The king opened parliament in the autumn, when they voted him supplies to carry on the Dutch war, which he greatly needed ; for he was at that time paying a thousand pounds weekly out of his own private purse to relieve the sufferings caused by the plague.

[A.Dr 1666.] The following year opened sadly for Catharine, because it brought news of the death of her beloved mother, the Queen-regent of Portugal. All the court put on the deepest mourning, and were directed " to wear their hair plain, and to appear without spots on their faces." This referred to the patches of black plaster that disfigured the court ladies of that period. A few months later Cath-

arine removed with her ladies to Tunbridge Wells again for the summer. This was a favorite resort for the fashionables during the seventeenth century, Queen Catharine having made it so by her patronage. There, under the shadow of spreading trees, the gay company would promenade in the morning while drinking of the waters. On one side of the avenue, formed by the trees, were little shops filled with toys and all sorts of fancy articles; on the other was a market. Neat-looking cottages, built here and there over a mile and a half of ground that surrounded the wells, formed the dwelling-places of the visitors, who would assemble on the green in the evening just before sunset for a dance. After dark they would adjourn to the queen's palace, where all sorts of amusements were indulged in for several hours. Catharine dispensed with ceremony at this watering-place, and endeavored to enhance the enjoyment of everybody by so doing. As a surprise to the king she sent for some actors, who performed comedies for the entertainment of the court. One member of this company was the celebrated Nell Gwynne, a beautiful actress, who afterwards became a lady of the queen's bed-chamber.

While the king and queen, surrounded by their court, were thus engaged making pleasure the business of their lives, the aspect of public affairs was most gloomy. The poverty caused by the ravages of the plague had rendered it impossible to collect taxes, consequently the supplies voted by parliament for the carrying on of the war were not forthcoming. France had formed an alliance with Holland, and England was at war with both powers. Added to these troubles was this: the country was filled with hirelings of exiled Roundheads, who, while pretending to be patriots, were really spie§, dishonorably intriguing to raise an insurrection in England.

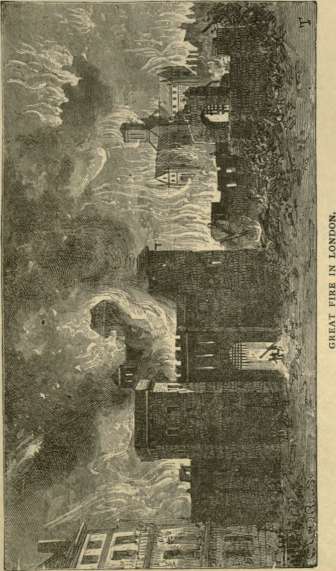

On the second of September a fire broke out in a baker

shop, at the corner of Thames street, and spread with frightful rapidity. It raged for four days, and the air was filled with the shrieks and lamentations of the men, women, and children, who rushed from one place to another after being obliged to desert their homes, knowing not whither to turn in order to save themselves from the devouring flames and the tottering churches and dwellings. The king and the Duke of York worked with the firemen, commanding, encouraging, and rewarding them ; and it was the presence of mind of the latter that stopped the fire at last, by blowing up several houses. This precaution saved the old Temple Church, the Tower, and Westminster Abbey. It was in seasons of danger and disaster that King Charles II. always appeared to the greatest advantage, by displaying a paternal care for the welfare of his subjects. After the fire he caused tents and huts to be erected in the vicinity of London for those who were left homeless, and provided them with food and fuel. He was, besides, remarkably lenient to those who could not pay taxes, because of the poverty occasioned by the plague, though he was thereby deprived of the means to pay his seamen, and obliged to order the ships to lay-by.