Agnes Strickland's Queens of England (24 page)

Read Agnes Strickland's Queens of England Online

Authors: 1796-1874 Agnes Strickland,1794-1875 Elizabeth Strickland,Rosalie Kaufman

Tags: #Queens -- Great Britain

All that remains of this building shows what a splendid one it must have been, but the storms of revolution have passed over it and left it almost in ruins.

The Earl of Peterborough was anxious to get to England with his charge as quickly as possible, but Mary Beatrice became so ill that she was unfit to travel for several weeks. Her disease was a low fever, occasioned by the mental anxiety she had endured for so many weeks. After her recovery the young duchess visited Versailles, where she was received with the highest consideration, and enter-,tained with all the splendor of that court. It was a dreadful ordeal for so young and inexperienced a girl to know just what degree of attention to accord each person without too much condescension on her own part, but particularly so for one who had no taste for the formalities of royalty, and greatly preferred the seclusion of a cloister. But Mary Beatrice excited admiration for her beauty and charming manners, of which the king showed his appreciation by making her some costly presents. She had already received jewels valued at twenty thousand pounds from her unknown husband, which she wore on state occasions while in France.

Mean\vhile a strong party in England had leagued itself, under the leadership of the Earl of Shaftesbury, for the purpose of destroying the Duke of York, and of getting the reins of the government in their own hands. This was no easy matter, because his services in his country's cause, his energy, and his high sense of honor, had rendered him one of the most popular of princes ; but the party opposed to him were ready to resort to any measures, no matter how vile, to gain their end.

Knowing this, the duke had managed his marriage with the utmost secrecy and despatch, because the strongest avowed point of opposition was his adherence to Catholicism, which his alliance with a Catholic princess would naturally stfengthen. So when parliament met, on the twentieth of October, they were perfectly astonished and highly indignant to hear from the king's lips that the duke was already married to the Princess of Modena, who was even then on her way to England. The infuriated Commons petitioned their sovereign " to appoint a day of general fasting, that God might avert the dangers with which the nation was threatened."

Charles told them that they might fast as much as they pleased, though he knew that by so doing they merely desired to show their contempt for what they called the " popish marriage," though the pope had positively withheld his consent to it. The members of the king's own cabinet became alarmed at the threatened storm, and urged his majesty either to forbid the princess to leave Paris or to dismiss his brother from court, and insist upon his leading the life of a country gentleman. Charles indignantly refused both propositions.

The day after parliament met Mary Beatrice landed at Dover, where her husband awaited her on the beach, and all the citizens had collected to get a sight of her.

The duke received her in his arms, and was charmed with her at the outset, as well he might have been ; but she, poor child, was not so favorably impressed with a man old enough to be her father, and showed her aversion plainly. This did not discourage the groom, who treated her with courtly attention, feeling convinced that he should win her heart in time.

In the presence of his suite and the bride's, besides a large number of Dover people, the Duke of York was married to Mary Beatrice according to the church of England rites, and the little ruby ring placed on her finger that day was more highly valued to the end of her life than any jewel the princess possessed.

The second day after the marriage the bride and groom, attended by the Duchess of Modena, and her brother-in-law, the Prince Rinaldo d'Estd, besides the members of their court, set out for London, King Charles went down the river with his court, in the royal barges, to meet the bridal suite, and received his new sister-in-law with every mark of affection ; then he conducted the party to Whitehall, where his queen vied with him in her acts of loving attention to the bride.

Even her enemies were for the time being disarmed when they gazed on the lovely, innocent countenance of the young bride ; and at King Charles's court she was much admired and esteemed.

The Duke and Duchess of York established themselves at St. James's Palace, where all the foreign ambassadors called to congratulate them, and where they held their courtly receptions as regularly as the king and queen did theirs at Whitehall, though on different days. King Charles was devoted to his brother, and soon became warmly at tached to his wife, but a little coolness was early established between Queen Catharine and the Duchess of York in

this way: It had been stipulated in the marriage treaty that the duchess was to have the use of the CathoUc chapel at St. James's which had been fitted up by the queen-mother, Henrietta, for herself and her household. But King Charles, knowing how unpopular any display of her religion at that time would make his brother's wife, influenced Catharine to claim it as one of her chapels, and had a private apartment in the palace fitted up for the devotions of the young duchess and her suite. This was a piece of friendship on the part of the king that was not appreciated by his sister-in-law, who laid the blame on the queen, with whom she felt quite offended.

At the end of the year the Duchess of Modena was called home by some intrigues that had been begun during her absence; but although Mary Beatrice was sorry to part with her, she had by that time begun to love her husband so much that the parting was not so great a trial as it would otherwise have been, and the love that was implanted in her heart developed into a devotion that lasted to the day of her death.

The first years of her married life were passed by the young duchess in a succession of gayeties. She was often annoyed because her husband treated her like a child, but as she was little older than his daughter this is not surprising. In later years circumstances developed the force of her character, and won the respect and admiration that she truly merited.

She had the good sense to study English, and soon became a perfect mistress of the language.

[A.D. 1675.] Mary Beatrice had a little daughter born about a year after her marriage. This was a great pleasure, but it was soon marred by the duke's refusal to have the baby baptized a Catholic. He did not object himself, but explained to his wife that their children belonged to the

nation and would be taken from them if not btought up according to the established church, adding that is was besides the king's pleasure, to which they must submit. The youthful mother appeared to yield, but sent for her confessor, Father Gallis, and had the child baptized on her own bed according to the rites of the church of Rome.

When the king came a day or two later to make arrangements with her and the duke for the christening of their child, Mary Beatrice told him that "her daughter was already baptized." Without paying the slightest attention to this assertion, his majesty ordered the little princess to be borne to the royal chapel, where she was christened by a Protestant bishop, her half-sisters, Mary and Anne, acting as sponsors. The baby was named Catharine Laura after the queen and the Duchess of Modena, and the Catholic baptism was kept a profound secret, though it must have been a subject of annoyance to the king.

A fortnight later some ver}^ severe laws were made against the Catholics. One of them forbade any British subject from officiating as a Romish priest, either in the queen's chapel or elsewhere; another prohibited any adherent of the Catholic, church to set foot in Whitehall or St. James's Palace, the penalty for such an offence being imprisonment. This law of course kept the Duchess of York and the Catholic ladies of her household from the king's palace, but the young mother was so wrapt up in her baby that she was indifferent to almost anything besides. She was happy with her husband also, and lived on terms of close friendship with her step-daughters, who never accused her of the slightest unkindness to them, even in later years, when they would have been pleased to bring any unfavorable accusation against her. But the young mother was soon to be deprived of the infant she loved so fondly, for it died of a convulsion before it was ten months old.

This was, of course, a great sorrow to Mary Beatrice, but she was not permitted to indulge it very long, for before the close of the year she had to attend a feast given by the lord mayor, and a ball at her own palace.

[A.D. 1676.] Another princess was born the next year, and this time there was no secret baptism. That ceremony was performed by Dr. North, Master of Trinity College, and the child was named Isabella. She lived to the age of five years.

[A.D. 1677 ] The following year the marriage between the Princess Mary and the Prince of Orange was solem nized; and it was this union that proved so disastrous to the fortunes of the Duchess of York, her husband, her children.

There was much rejoicing in the household of the Duke when a little prince made his appearance. He was christened with great pomp by the Bishop of Durham, and no less a person than the king himself, assisted by the Prince of Orange, acted as sponsor. Charles bestowed his own name on his nephew, and created him Duke of Cambridge. The little fellow died the following month, and was interred, as his sister had been, in the vault of Mary Queen of Scots, at Westminster Abbey.

The duke grieved more for the death of this boy than he had for any of his children. The Prince of Orange wrote a letter of condolence; but, as he was then plotting against his royal father-in-law, and as the death of the little prince opened the way to the throne for his wife, it is not probable that he was sincere in his expressions of sympathy. But Mary Beatrice was ignorant of this, and when she heard that the Princess of Orange was ill she planned a visit to her, which, after obtaining the king's consent, she undertook, in company with Princess Anne and her lord chamberlain, the Earl of Ossory.* As it was her desire

to ascertain the true sfete of Princess Mary's health, and to afford her comfort, the duchess travelled incognito, and sent a man on before to hire for her a small house not far from the palace. This was done to secure free intercourse among the three ladies without any of the formality required by court etiquette.

[A.D. 1678.] Although the visit was a flying one, the duchess found a storm gathering around her husband on her return which soon compelled him to give up his seat among the state councillors. His friends advised him to retire to the continent with his family; but his proud spirit revolted from any move that would have the appearance of guilt or cowardice. The king urged him to baffle his enemies by returning to the church of England, but he refused to act in opposition to his conscience. Then for the sake of peace, which the " merry monarch" would have purchased at any cost, Charles advised his brother to go abroad before the next session of parliament. James consented, providing the king would command it in writing, but he scorned the idea of running away. The order was given in the form of an affectionate letter, and on the fourth of March the Duke and Duchess of York embarked for Holland. They were not permitted to take their little daughter Isabella to share their exile, which was a great deprivation to both parents.

[A.D. 1679.] The king called on the day of their departure to bid farewell, and was much affected at parting with the brother whom he loved so well. The weather was very stormy, and wiping the tears from his eyes Charles said : "The wind is contrary; you cannot go on board at present."

Mary Beatrice, who considered that her husband was being sacrified to secure his brother's peace of mind, replied with spirit, *' What, sir, are you grieved ? — you who

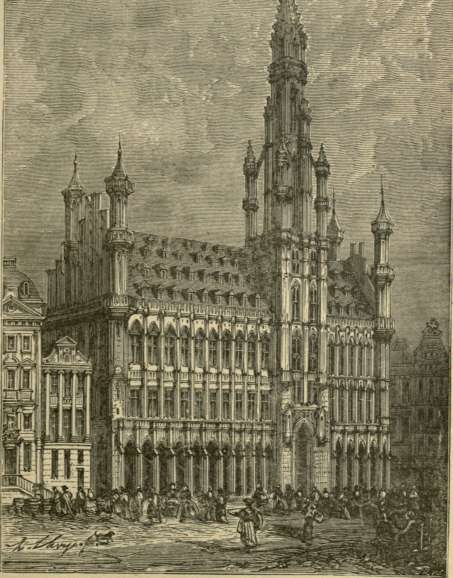

THE HOTEL DE VILLE.

send us into exile ! Of course we must go, since you have ordained it." She regretted this speech later, because she knew that Charles had only yielded to the clamor of her enemies.

The duke and his wife arrived at the Hague a week later, and were received by the Prince of Orange with every demonstration of respect. Later they removed to Brussels, where they occupied the house Charles II. had lived in before the restoration.