Agnes Strickland's Queens of England (47 page)

Read Agnes Strickland's Queens of England Online

Authors: 1796-1874 Agnes Strickland,1794-1875 Elizabeth Strickland,Rosalie Kaufman

Tags: #Queens -- Great Britain

While at this cottage, the victory of Oudenarde was announced to her majesty. When she heard that it had been won at the cost of two thousand lives, she exclaimed : " O Lord! when will all this dreadful bloodshed cease ?"

Nevertheless, etiquette required her to write a letter of congratulation and thanks to the victorious Duke of Marlborough, which she did at once.

Public thanksgiving for the victory took place in the usual way at St. Paul's Cathedral on the nineteenth of August. As her husband was the victor, the Duchess of Marlborough considered herself the heroine of the day, and bustled about to make herself as important as possible. Her office of mistress of the robes imposed upon her several duties, and among others, the arrangement of the queen's jewels as she chose to have them worn. When the royal cortege was approaching the cathedral, the duchess chanced to cast her eyes over the costume of her majesty, and observed that the jewels were absent. This was a mark of disrespect that she would not stand, so she began scolding in such way that the queen lost her temper, and the two ladies quarrelled and abused each other until they got inside the church, when the duchess angrily bade the

queen "to hold her tongue." This was too much. Her majest)'' had borne a great deal from ii^r friend, but such an insult aroused her indignation. Perhaps the duchess repented of her hasty speech ; for a day or two later she took occasion to send the following humble note with a letter from her husband :—

" I cannot help sending your majesty this letter to show how exactly Lord Marlborough agrees with me in opinion that he has now no interest with you, though when I said so in the church last Thursday you were pleased to say it was untrue."

" And yet, I think he will be surprised to hear that when I had taken so much pains to put your jewels in a way that I thought you would like, Mrs. Masham could make you refuse to wear them in so unkind a manner; because that was a power slie had not thought fit to exercise before.

" I will make no reflections on it, only that I must needs observe that your majesty chose a very wrong day to mortify me when your were just going to return thanks for a victory obtained by my Lord Marlborough ! "

No doubt the queen thought, as anybody might, that a great deal of fuss had been made about a trifling matter, for she sent the following reply : —

" After the commands you gave me on the thanksgiving day not to answer, I should not have troubled you with these lines; but, to return the Duke of Marlborough's letter safe into your hands, and for the same reason, I do not say anything lO that or to yours which enclosed it."

What a pity it is that the queen did not always behave with the same dignity, when dealing with the haughty, domineering duchess ! If she had, many a heartache and many an insult she might have spared herself. Another letter, still more meek in its tone, was sent in reply; but

open warfare had been declared between the friends of former years, and the duchess had no chance of ever regaining her sway over her sovereign's heart.

Her husband's ill health was a matter of greater concern to Queen Anne just then than anything else could be; and, within a week after the stormy scene at St. Paul's, she set out with him for the west of England, hoping that change of air might benefit him. They travelled by easy stages until they arrived at Bath, a favorite resort, where Anne often went for her own health.

That autumn a fine statue of the queen that had been modeled by Bird, the sculptor, was finished, and placed at the west door of St. Paul's, where it still stands. Although it is said to be a perfect likeness, it is considered by no means an excellent work of art, notwithstanding its having cost over five hundred pounds. Just when it was erected, there was a report current that the queen intended to free herself from the tyranny of the Duchess of Marlborough. That was enough to strike terror to the hearts of the Whigs; for with their ruler in disgrace, they could hope for no better fate than banishment, — at least from the public treasury, whence they were generously helping themselves. Their only chance then was to calumniate the queen and make her as unpopular as possible, so that when it came to the point their party would be too strong for her to resist. So they accused her of all sorts of vices in circulars that were daily distributed among the populace. One charge brought against her was that of intoxication, because one of her enemies had said " that she got drunk every day as a remedy to keep the gout from her stomach." Had this been a fact, the Duchess of Marlborough would certainly have been one of her first accusers, but even in her most malignant moods she never mentions such a fact. However, the Whig physician. Dr. Garth, wrote an epigram

which was found fastened to the statue the day after it appeared in front of St. Paul's Cathedral. It ran thus :—

'• Here mighty Anne's statue placed we find, Betwixt the daring passions of her mind; A brandy-shop before, a church behind -. But why thy back turned to that sacred place, As thy unhappy father's was to grace ? Why here, like Tantalus, in torments placed, To view those waters which thou canst not taste ? Though, by thy proffer'd globe we may perceive, That for a dram, thou the whole world would'st give."

It must be remembered that this was written by an enemy; very different is the poetry under an engraving of the queen and her consort at the British Museum, and forms a pleasing contrast to the above :—

" The only married queen that ne'er knew strife. Controlling monarchs, but submissive wife, Like angels' sighs her downy passions move, Tenderly loving and attractive love. Ot every grace and virtue she 's possessed — Was mother, wife, and queen, and all the best"

On her return from Bath the queen congratulated herself on her husband's improvement; but he knew that it was only momentary, and when she was preparing for a hunting excursion at Newmarket he begged her not to leave him. He felt that he had not long to live, and he was right, for he died before the close of the month, at Kensington Palace. Queen Anne had been a happy wife for twenty years, and the death of the prince-consort was a dreadful blow, though she had witnessed his declining' health for many months. Even at the moment of her greatest bereavement, the Duchess of Marlborough forced herself into the presence of the queen, and insisted upon leading her from the room after the prince was dead. Anne treated her with excessive coldness, merely submitting to

the arrangements she had made for her removal to St. James's Palace, because she was too miserable to oppose her.

The interment of the prince-consort took place on the thirteenth of November. The funeral was private, which only means that it was performed by torchlight at night, for it was attended by all the ministers and great officers of state. The court went into mourning, and all the theatres were closed for a month.

[A.D. 1709.] The duchess continued to watch Queen Anne very closely, and was shocked when fires were ordered to be made in the apartments occupied by the late prince-consort, also in those below, the two being connected by a private back staircase. They were for her majestj' and Mrs. Masham, and strong suspicions were aroused in the mind of the active watch-dog that this arrangement was effected for the purpose of granting interviews with her political opponents. She, therefore, took the queen to task for such an irregular mode of proceeding, and raising her eyes and hands in holy horror, said : " I am amazed ! " But the queen made no reply, and probably no change in her plans just then, for she was so absorbed in grief that she took no interest in anything for many months. She was not sufficiently recovered in spirits to open parliament the following May, but she issued a general pardon, particularly to those who had been in correspondence with the Court of St. Germain, and it was confirmed. This was for the protection of Lord-treasurer Godolphin as well as herself, for she was always in mortal terror lest the Marlborough family should proclaim to the world the part she had played in the revolution. Therefore she dared not exasperate the duchess, nor could she remove her until the duke had ac-cumulatea wealth sufficient to render the stability of the government a matter of personal interest with him. The

duchess understood this perfectly, and made the queen feel her power, as we have seen.

Another victory won by the Duke of Marlborough forced her majesty to reappear in public. This was Malplaquet; but twenty thousand British subjects had lost their lives on the battle-field, and Queen Anne joined the thanksgiving procession with a heavy heart, and with eyes red and swollen from weeping. She could not rejoice over a victory at such a sacrifice. The details of the war filled her with horror, and she longed to put an end to the dreadful slaughter; but the victorious duke's return gave her little encouragement in that respect, for he demanded of the queen " her patent to make him captain-general for life, because the war would not only last through their lives, but probably forever." Anne was perfectly amazed at this extraordinary speech, but dismissed the subject by answering: "That she would take time to consider it," and afterwards asked Lord-chancellor Cowper: " In what words would you draw a commission which is to render the Duke of Marlborough captain-general of my armies for life ?"

Lord Cowper stared as though he thought her majesty had taken leave of her senses, and then warmly expressed his disapproval of such a proceeding. " Well, talk to the Duke of Marlborough about it," replied the queen, without telling him that she had never intended to make the appointment. Cowper obeyed, and assured the duke " that he would never put the great seal of England to such a-commission." The Duke of Argyle and several other noblemen were secretly brought to confer with the queen on this subject, and she asked what she should do if her refusal to appoint Marlborough captain-general for life should prompt him to make an attack on the crown. The Duke of Argyle replied: " Her majesty need not worry, for he would undertake, if ever she commanded it, to seize

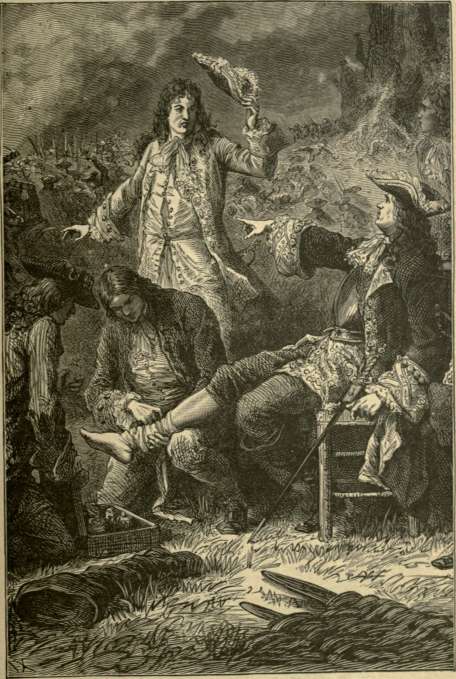

AT MALPLAQLET.

the Duke of Marlborough, at the head of his troops, and bring him before her, dead or alive ! "

It was Harley who brought this secret council together, and the Marlboroughs hated him worse than ever when they discovered it. They had gone a step too far, and the division in their own party in consequence caused the duke to withdraw his request.

Her majesty having expressed her intention to lay aside her mourning at the Christmas festival, which was close at hand, intercourse became necessary between her and the duchess, who was mistress of the robes. This was a signal for the renewal of hostilities, beginning with lodgings and situations for chambermaids and other members of the royal household ; for the tyrant duchess insisted on her right to make every appointment of that sort. Many severe letters passed between her and the queen on this subject, and it became necessary to inform her on one or two occasions that she had rather overstepped the mark when claiming " her rights." The storm was at its height when the duchess discovered that her majesty, without asking permission, had ordered a bottle of wine to be allowed daily to a sick laundress who had washed her laces for twenty years. Thereupon she raved like an angry fishwife, and her voice was raised to such a pitch that the footmen at the back-stairs heard every word she uttered. The queen, unable to contend with such a vixen, rose to leave the room ; but the irate duchess whisked past her, slammed the door, posted her back against it, and informed her royal mistress " that she should hear her out, for that was the least favor she could do her for having set the crown on her head and kept it there." This tirade was kept up for nearly an hour; then Sarah of Marlborough finished by saying " that she did not care if she never saw her majesty again," and flounced out of the room as the queen calmly

replied, " that she thought, indeed, the more seldom the better."

It is hard to comprehend how a sovereign could submit to such humiliating scenes, but she knew that the chief cause of complaint with the duchess regarding the wine arose from the fact of the laundress having once served Mrs. Masham, who, it was supposed, was the instigator of the queen's beneficent act. Even then such petty jealousy, and such absurdly, undignified behavior give a poor opinion to the world of the lofty duchess's head and heart. She and the queen scarcely spoke after this ; but a day or two before Christmas she wrote a letter to her majesty lecturing L^r on the necessity of entering on the religious services of the season with a spirit of meekness and forgiveness for injuries.* Some passages were so insolent that the letter was not answered; but as the queen passed to the altar of St. James's Chapel, she bestowed a gracious smile on the writer.

[A.D. 1710.] The new year opened with the queen at Hampton Court, considering the best means for breaking loose from the trammels of the Whig party, headed by the Marlborough family. It was a difficult step, but she was determined to take it, and for that purpose summoned Harley to her presence in the most secret manner possible. His advice was to begin by filling the post of lieutenant of the Tower, just vacated-by the death of the Earl of Essex, as her majesty chose, without consulting anybody. In consequence, the Earl of Rivers was appointed to this great office, whereupon the duchess flew into a rage, and declared that a man who had borne the nickname of " Tyburn Dick " in his youth, having barely escaped conviction at the criminal bar for robbing his own father, was no fit person for such an honor. But this is how he had managed to obtain it: No sooner did he hear of the death