Agnes Strickland's Queens of England (48 page)

Read Agnes Strickland's Queens of England Online

Authors: 1796-1874 Agnes Strickland,1794-1875 Elizabeth Strickland,Rosalie Kaufman

Tags: #Queens -- Great Britain

of Essex than he hastened to the presence of the Duke of Marlborough with the news, adding a request that the great man would interest himself with the queen to secure the vacant post for him. It was not the duke's way to give a decided refusal, nor did he hesitate to make promises that he had not the slightest intention of fulfilling; so, after complimenting "Tyburn Dick," and loading him with offers of kindness, the duke advised him to " think of something better than the lieutenancy of the Tower, as the place was not worthy of his talent." However, the man was determined, and said : " He was going to ask the queen for the appointment, and would tell her that his grace had no objection." Marlborough, who never dreamed that the queen would take an important step without consulting him, told Lord Rivers that " he might say so if he pleased;" whereupon the petitioner lost not a moment in seeking an audience of the queen, who, on hearing what Marlborough had said, with the adornments Lord Rivers chose to add, made the appointment at once. As the new lieutenant of the Tower passed out of the royal presence he made the duke, who was just entering, a most profound bow, and rubbed his hands with delight as he left the palace. But we know that the duke had not intended that Rivers should succeed Essex, and the object of his present visit to her majesty was to propose the Duke of Northumberland instead. He was amazed to find that he was too late, and made serious complaints to the queen, who asked him, " whether Earl Rivers had asserted what was not true." The duke could not say that he had, and so there was no redress; but, when her majesty followed up this appointment by one for colonel of a regiment. Lord Godolphin was as indignant as the duke himself, and she was forced to withdraw.

Before departing for his campaign the Duke of Marl-

borough sought an interview with the queen, and requested that his wife might be permitted to remain in the country as much as possible, and that as soon as peace was made her resignation might be accepted in favor of her daughters. The queen granted the first part of the request with alacrity, delighted at the prospect of being relieved of the presence of her tyrant, but' made no reply with regard to the daughter's, on whom she intended to bestow no favors whatever.

Now a most important trial took place this year, that created intense excitement, and occupied the court for three entire weeks. It was that of Dr. Sacheverel, a representative of an ancient Norman family, who had been impeached, chiefly on charges connected with the church; but, as this affair is excessively dry and uninteresting, it is only necessary to mention it because of its bearing on the position of Queen Anne. Dr. Sacheverel belonged to her party, and she was so much interested in his trial that she sat to witness it every day in a curtained box at Westminster Hall. At the end of the contest the doctor was sentenced to suspend his preaching for three years, which was almost equivalent to acquittal. The lower classes showed clearly that they were for their "good Queen Anne," and that they were ready to rise in her defence against the Whig ministry whenever she should say the word. This feeling, which was so clearly manifested, encouraged the queen to take measures to free herself from the Marl boroughs and their party. The duchess made several attempts at private interviews, but was always repulsed, until she became convinced at last that Queen Anne would see her only at public receptions, or when official duties required it. The Marlborough family conclave were convinced that their days were numbered when the Tory Duke of Shrewsbury was made lord-chamberlain

of the royal household in place of the Whig Marquis of Kent. This was followed up by the removal of Lord Sunderland from his office of secretary of state. This young man, as son-in-law of the Duchess of Marlborough, had heard her majesty spoken of with so much disrespect that he had on several occasions behaved most rudely, and he was removed for this reason, more than for any adherence to the Whig party.

The colonel whom her majesty had desired to appoint when she met with such" violent opposition was Jack Hill, brother to Mrs. Masham, her favorite bed-chamber woman. She made another attempt, and positively declared that she would not sign a single one of the Duke of Marlborough's numerous commissions until her will was obeyed in this matter. This was alarming, for the duke received payment for these commissions; so he gave in at once and signed Jack Hill's appointment without further parley. Queen Anne forthwith sent the new officer to make an attack on Quebec, as the conquest of Canada was deemed an important measure for the security of the British possessions in America. Much to the delight of the Marlborough party. Jack Hill's attempt was a failure.

The duchess was so angry at the dismissal of her son-in-law that she sent a letter to her husband, which he was to copy and forward to her majesty as though it were expressive of his own wrath, but he tossed it into the fire. But the irrepressible duchess had it intimated to the queen through David Hamilton, one of the court physicians, " that if she persisted in ruining her party all her fond and friendly letters of former days should be published," and forwarded one lest" dear Mrs. Morley " might have forgotten how high her opinion had been of " Mrs. Freeman," at that date. The queen kept her own letter, and demanded all the rest,saying: "She was sure the duchess

did not now value them." Not another one found its way to the queen, for they were weapons too powerful to be lightly parted with.

The next dismissal was that of the queen's long-trusted lord-treasurer, Godolphin. Several of his friends expressed their concern at this move on the part of her majesty. She merely replied, " I am sorry for it, but could not help it," and then turned out Lord Rialton, another of the Marlborough sons-in-law. The office of lord-treasurer was placed in the hands of seven commissioners, with Mr. Harley at their head.

The Duke of Marlborough wrote his wife that he had heard of an assassin being on his way from Vienna to England with designs against the queen's life, and requested that the utmost care might be taken lest he should gain access to the royal presence. Here was a chance for the duchess to ingratiate herself once more in the queen's favor; so she drove post haste to court, and with a most important air demanded admittance, " on a matter of life and death." Her majesty refused to see her, whereupon the duchess sent her husband's letter by a messenger. One of Queen Anne's peculiarities was indifference to personal danger, so without heeding the warning, she merely returned the duke's letter with a line, saying: "Just as I was coming down stairs I received yours, so could not return enclosed until I got back." This was the last written sentence that ever passed between the queen and the duchess.

Many of the ancient nobility who had never approached the English court since the revolution paid their respects to Queen Anne as soon as she had rid herself of the Marl-boroughs. But the principal one of that party still remained, for nobody had the courage to approach the terrible creature with any but flattering news; so it was deter.

mined to await the return of the only person in the world who could manage her, and that was the duke himself.

Meanwhile the daring woman, who retained her office in defiance of sovereign, prime minister, and all the other high officials, drove about town in her magnificent coach, and made visits to different members of her party for the purpose of calumniating the queen. She was not permitted to enter the royal presence, and kept the gold keys that really belonged to the new officials; but she boldly declared ' that her majesty would soon want new gowns, and then she would be compelled to come to her to give orders for them." But she was mistaken, for on the return of the duke in December there was to be an end of her influence with the queen in every particular. On his arrival in London the duke took a hack and drove direct to St. James's, where he had a private half hour's interview with the queen. In his peculiar plaintive tone of voice he lamented his connection wich the Whigs, and told her majesty " that he was worn out with fatigue, age, and misfortunes," and added " that he was neither covetous nor ambitious," — at which she could scarcely suppress a smile. At the close of the interview the queen requested him to tell his wife " that she wished back her gold keys as groom of the stole and mistress of the robes." The duke remonstrated, but the queen merely replied : " It was for her honor that the keys should be returned forthwith."

The duke entreated that this matter might be delayed until after the peace, which must take place the ensuing summer, when he and his wife would retire together. The queen would not. delay the return of the keys one week. The duke fell on his knees and begged for a respite of ten days; the queen compromised, and named three as the utmost limit. Two days later the duke ngain presented

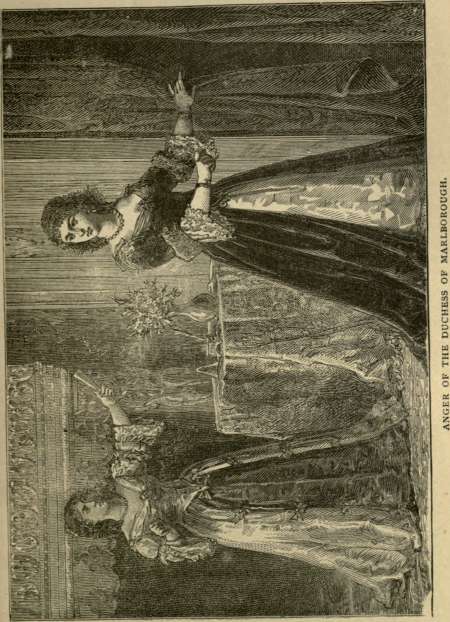

himself at St. James's on urgent business; but her majesty refused to speak with him, unless he had brought the gold keys. Thereupon he returned home to get them, when a stormy scene ensued, which ended by his wife throwing the keys at his head. When the queen received them from the duke's hands, she said, " she valued them more than if he had brought her the spoils of an enemy."

[A.D. 17II.] Early in the following year Queen Anne divided between the Duchess of Somerset and Mrs. Ma-sham the ofhces formerly held by the Duchess of Marlborough, the former being made mistress of the robes and groom of the stole; the latter, keeper of the privy-purse. On the second of May Queen Anne's uncle, the Earl of Rochester, died suddenly of apoplexy.

Although Anne was his own niece, the earl had never concealed from her his opinion that she had no right to the crown she wore; but he had consented to aid her in the government, and was, as we know, made president of the council. But he entertained to the last day of his life the hope that he should see the son of James II. restored to the throne, and was the means of causing several letters to pass between James Stuart, or the Chevalier de St. George, as he was then called, and the queen.

The Duke of Buckingham succeeded Rochester; and, being a relation of the queen's, a most friendly feeling existed between them. Once, after reading a long letter presented by him from her brother, the Chevalier de St. George, in which he set forth his claim to the throne. Queen Anne turned to Buckingham, and asked : " How can I serve him, my lord ? You well know that a papist cannot enjoy this crown in peace. Why has the example of my father no weight with his son ? He prefers his religious errors to the throne of a great kingdom. He must thank himself, therefore, for his own exclusion. All would be easy if he would

join the Church of England. Advise him to change his religion, my lord."

Although Queen Anne spoke thus, she knew that her brother would not renounce Catholicism, and she had no intention of aiding him to the throne unless he did. She favored the succession of the Protestant house of Hanover; but the Princess Sophia, who was the heiress of that line, had emphatically declared that if the young prince and princess of the house of Stuart would become members of the Church of England, their claim should never be disputed, nor would it have been, as future events proved.

Throughout the summer Queen Anne suffered so much from gout that she could scarcely stir from her bed, but she held her receptions all the same, and the crowd was often so great that only those nearest the bed could get sight of her. In the autumn she was better, and received ambassadors from France to negotiate for peace. One evening in October her majesty mentioned publicly at supper " that she had agreed to treat with France, and that she did not doubt but that in a little time she should be able to announce to her people that which she had long desired, — a general peace for Europe."

But she had not yet secured peace at home, for matters took such a turn that the new ministry insisted on the removal of the Duchess of Somerset, and when her majesty returned to the palace from the parliament meeting she asked for the Duchess of Marlborough. One of the latter's friends rushed to her, without a moment's delay, and told her that if she would go to the queen then she might, with a few flattering words, overthrow her enemies, but she indignantly refused. The queen had new ground for complaint against the duchess when she took possession of her new palace, just completed in St. James's Park ; for the apartments she left in the queen's palace were bereft of locks,

bolts, mirrors, marble slabs, and pictures, and looked as though a destructive army had sacked them. The duke lamented the strange conduct of his wife when he got back, but declared " that there was no help for it, and a man must bear a good deal to lead a quiet life at home." But this confession did not prevent his dismissal from the army. He was succeeded by the Duke of Ormond, who was ordered not to gain victories, but to keep the British forces in a state of armed neutrality until peace was concluded.

It was at this time that Mr. Masham was made a peer, because her majesty was urged to it by some of her ministers, but she said that she had never any intention of makmg Abigail a great lady, and feared that by so doing she had lost a useful servant. But Lady Masham promised to continue in the office of dresser to her majesty even though she was a peeress.