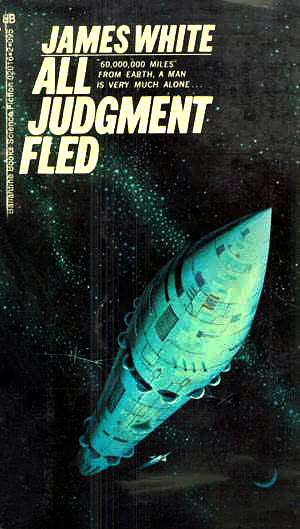

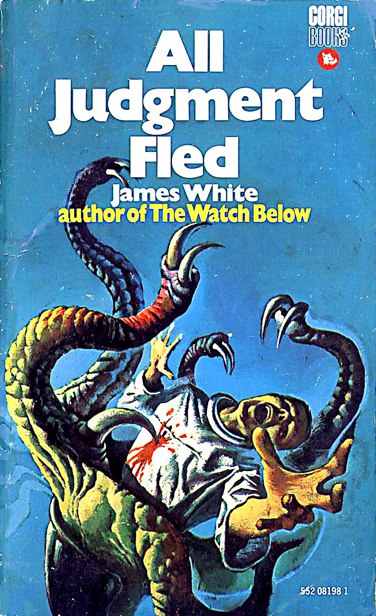

All Judgment Fled

Authors: James White

All Judgment Fled

All Judgment Fledby James White

Sixty million miles from Earth, embroiled in

all the perils of First Contact, astronauts

haven't much time for politicians. Back on

Earth, though, the actions of humanity's

hastily chosen representatives are the very

stuff of politics. The result is stress -- for the

astronauts, and for the men who are supposed

to dictate their actions from Earth. And stress

in these conditions makes a tricky situation

really dangerous. It can cause unnecessary

deaths, it can drive a man mad -- it can also

bring out the unexpected in a man's character.

When the alien ship took up a position in

space some sixty million miles from Earth, it

violated all the laws of motion. Clearly its

drive was something new and unimaginably

important. In any case, it was indisputably

alien, the first such phenomenon to come the

way of startled humanity. There was no time

to lose. Six astronauts were hastily assembled

and sent out as Earth's representatives, to be

the eyes, the ears, and the ambassadors of the

world. They were warned before they went

that they were to be as circumspect as possi-

ble, that all their actions would be reviewed on

Earth and would affect the perennially deli-

cate political situation there. But politics is

the art of the possible. Aliens do not conform

to the rules. They are by the nature of things

unpredictable. Sometimes they are simply

savage . . .

James White has a unique talent for con-

structing believable but utterly alien aliens,

and for wrapping human contact with them in

a cloak of wild adventure. Here he piles ten-

sion on tension, culminating in a splendidly

unexpected but satisfactory climax.

All Judgment Fled

by James White

WALKER AND COMPANY

New York

Copyright © 1969 by JAMES WHITE

Second Printing

This novel first appeared as a serial in If Magazine, © 1967 by

Galaxy Publishing Corporation.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or me-

chanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any infor-

mation storage and retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the Publisher.

All the characters and events portrayed in this story are

fictitious.

Published in the United States of America in 1969 by the

Walker Publishing Company, Inc. by arrangement with

Ballantine Books, Inc.

Published simultaneously in Canada by The Ryerson Press,

Toronto

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 70-86388

Printed in the United States of America

O judgment, thou art fled to brutish beasts,

And men have last their reason.

Shakespeare

in Sagittarius and its presence was blamed on mishandling or faulty

processing. But a second exposure of the same area showed a similar

scratch which began where the first one had left off and traced a

path which was unmistakably curved, indicating that it was altering

its own trajectory and could not therefore be a natural celestial

body. Immediately every instrument which could be brought to bear was

directed at the Ship.

spectro-analysis indicated a highly reflective surface suggestive of

metal and the great bowls of the radio telescopes gathered nothing at

all. By this time the Ship had taken up an orbit some twelve million

miles beyond the orbit of Mars, still without making any attempt to

communicate, and the decision was taken to sacrifice the Jupiter probe

in an attempt to gain more information about the intruder.

Jupiter Probe -- the unmanned observatory for the examination of the

Jovian system which was to have relayed its data to Earth for decades

to come -- was at that time relatively close to the alien ship. It was

thought that if the fuel reserve to be used for maneuvering inside the

Jovian system was used for an immediate and major course correction, the

probe could be made to pass within fifty thousand miles of the stranger.

the vessel which orbited silently and, some thought, implacably, like

some tremendous battleship cruising off the coast of a tiny, backward

island. It made no signal nor did it reply in any recognizable fashion

to those which were being made. For the probe's instruments showed the

object to be metallic, shaped like a blunt torpedo with a pattern of

bulges encircling its midsection, and just under half a mile long.

small, sophisticated dugout canoes were hastily modified and readied

for launching.

far enough into the philosophical implications of this thing. At present

that ship is a Mystery, but once we make contact it will then become a

Problem. There's a difference, you know."

mystery which has been broken down into a number of handy pieces, some

of which are usually related to problems already solved. And far be it

from me to impugn the thought processes of a fellow officer, but your

stand smacks of intellectual cowardice."

not cowardice," Walters returned, "and if we're to begin impugning minds,

it's my opinion that too much confidence -- you can call it bravery if

you like -- is in itself a form of instability which . . ."

brave?" said Berryman, laughing. "It seems to me everyone on this operation

wants to be the psychologist except the psychologist. What do you say,

Doctor?"

idiot it had been who had first likened the horrible sensation he was

feeling in his stomach to butterflies. But he knew that the other two men

were verbally whistling in the dark and in the circumstances he could

do nothing less than make it a trio. He said, "I'm not a psychologist,

and anyway my couch is full at the moment -- I'm in it . . ."

said Control suddenly.

"I have

to tell you that Colonel Morrison's ship had a three-minute hold at minus

eighteen minutes, so your takeoff will not now be simultaneous. Is this

understood? Your own countdown is proceeding and is at minus sixty seconds

. . . now!"

to touch the alien ship is a . . ."

the image of fearless, dedicated scientists exchanging airy persiflage

within seconds of being hurled into the unknown? Your upper lips must

be so stiff, I'm surprised you can still talk with them. Would you agree

that you may be overcompensating for a temporary and quite understandable

anxiety neurosis?

. . ."

Everybody

wants to be

a psychologist!"

no more, and still it increased. Even his eyes felt egg-shaped and his

stomach seemed to be rammed tightly against his backbone. How anything

as fragile as a butterfly could survive such treatment surprised him,

but they were still fluttering away like mad -- until accelerating ceased

and his vision cleared, that is, and he was able to look outside. Only

then did they become still, paralyzed like himself with wonder.

responsibility of brains both human and electronic on the ground. Their

short period of weightlessness ended as the second stage ignited, its

three G's feeling almost comfortable after the beating he had taken

on the way up. With his head still turned toward the port, McCullough

watched the splendor of the sunset line slide past below them to be

replaced by the great, woolly darkness that was the cloud-covered Pacific.

than toward Earth -- Morrison's ship. He knew it was the colonel's ship

because its flare died precisely three minutes after their own second

stage cut out.

made since Apollo -- they were now on a collision course with the

sixty-million-miles-distant Ship. A period of deceleration, already

precalculated, would ensure that the collision would be a gentle one,

if they managed to collide with it at all. For the alien vessel was a

perfect example of a point in space. It had position but no magnitude,

no detectable radiation, no gravitational field to help suck them in if

their course happened to be just a little off.

fuel finding it that they might not be able to return home, was to worry

McCullough occasionally. Usually he tried, as he was doing now, to think

about something else.

picked out by the naked eye -- at least by McCullough's middle-aged,

slightly astigmatic naked eye -- or it was hidden by the glare from the

monsoon season cloud blanket covering Africa and the South Atlantic. But

suddenly the colonel was very much with them.

as clear as the notes of a silver trumpet blowing the Last P -- I mean

Reveille . . ."

oxygen. Have you completed checking your pressurization and life-support

systems?"

possible. Use medication if necessary. At the present time I consider it

psychologically desirable for a number of reasons, so go to sleep before

your nasty little subconsciouses realize they've left home. That's an

order, gentlemen. Good night."

Walters said drily, "Even the colonel wants to be one," and Berryman

added, "The trouble, Doctor, is that your psychologists' club is not

sufficiently exclusive."

belonged to the most exclusive club on Earth, membership of which was

reserved for that very select group of individuals who at some time had

left the aforementioned planet. And like all good clubs or monastic orders

or crack regiments, there were certain rules of behavior to follow. For

even in the present day, members could find themselves in serious trouble,

very serious trouble.

by certain founder members who had been similarly unfortunate. They

were expected to talk quietly and keep control of themselves until all

hope was gone, then perhaps smash their radios so that their wives and

friends would not be distressed by their shouting for the help which

nobody could possibly give them when their air gave out or their vehicle

began to melt around them on re-entry.

Other books

One Song Away by Molli Moran

SS General by Sven Hassel

Scorpion's Advance by Ken McClure

An Angel Runs Away by Barbara Cartland

Masked Desires by Elizabeth Coldwell

The Genesis Plague (2010) by Michael Byrnes

Dangerous by Sylvia McDaniel

The Suicide Shop by TEULE, Jean

Garnet's Story by Amy Ewing

Touched by Death by Mayer, Dale