All That Is Bitter and Sweet (14 page)

We started out from Lincoln, Nebraska, on December 1, World AIDS Day. The eleven-city tour would take us across Iowa and Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Bono, Bobby, and Jamie Drummond, DATA’s chairman and chief organizer, chose to bypass the media-rich, oh-so-sophisticated East Coast and West Coast and focus on the interior, because, as Bono explained, it’s a place of strong communities and families, where the nation’s “moral compass resides.” He told one newspaper reporter, “We came to the heartland to get at the hearts and minds of America.” The plan was to engage people where they worshipped and where they lived, to dispel some of the myths about Africa as a vast, dysfunctional wasteland, and to put a human face on the AIDS catastrophe. We wanted to reach out to unlikely allies, such as blue-collar workers, evangelical Christians, small-town mayors, and regional newspapers, because we believed they would warm to the cause once they understood the depth of the crisis and knew that they could make a difference. As I often said, “It took an Irishman to remind me of President Harry Truman’s quote, that if you give Americans the facts, they’ll do the right thing.”

My job on the “Heart of America” tour was to emcee the events, articulate the problems that needed fixing, recite the grim statistics, and begin to address the issue of faith as the basis for this

cri de coeur

. I would also engage the crowds and make them comfortable with my good old American self before turning them over to the electrifying, hyperverbal Irish rock star who simply blew people’s minds as he exhorted them to greatness.

“This isn’t about charity, it’s about justice!” Bono would say as he took the stage. “We can’t fix every problem, but we must fix the ones we can!” He would take out his guitar and experiment with a song the band was thinking about playing at the Super Bowl, thrilling people with this privileged peek at U2 music in the making. By letting us into his world and opening his heart, he made every one of us want to be better.

There were also appearances by other celebrities and notables, such as Lance Armstrong; Chris Tucker; the famous epidemiologist from Harvard, Dr. Jim Kim (now president of Dartmouth College); nutrition expert Dr. Dean Ornish; and even Nebraskan multibillionaire investor Warren Buffett. Our traveling road show included speakers and performances by the Gateway Ambassadors, a mesmerizing Ghanaian children’s choir, some of them HIV-positive, with whom we prayed as a group before each rally. But we were all very clear that each evening centered on the testimony of Agnes Nyamayarwo, a Ugandan nurse whom Bono had met on a recent trip to Africa. It was her first time in America. Agnes’s story is devastating. She was a devout Catholic who’d had ten children with her husband, an American-trained agronomist. But her husband died of AIDS in 1992, having been infected outside their marriage, and she was left a single mother infected with HIV. In a sadly common African irony, she continued to work as a nurse, caring for others, while she herself had no medications for her HIV-positive status. Her eldest son, Charles, was so stigmatized by his father’s disease that he disappeared from boarding school and was never heard from again. This was perhaps the hardest part of her story to share each evening: not knowing where her boy was. Had he been run off, or fled? Had he been killed by bullies, as has been known to happen? Additionally, Agnes had unknowingly infected her youngest son, Christopher, in utero. She nursed him for two years before he died.

“Excruciating pain gripped my heart like a vise during those long hours, days, weeks, and months prior to his death,” she told one interviewer. “Looking at his deteriorating condition, tears would just flow from my eyes and it is then that he would say, ‘Mummy, why are you crying? I will be okay.’ His innocent face and words have always remained with me and filled many of my waking hours. His determination to get better always returns to haunt me, for I knew even then that without proper medication that he needed, Chris was fighting a losing battle.”

I listened keenly every time Agnes told her story. It was impossible to witness her grace and see her resilience and remain apathetic. Audience members would come up to us later and tell us that it was Agnes who made the crisis seem real, not like something happening to strangers in an alien world. Meeting this one woman made me realize how little I truly knew about the challenges of life in the global South.

When we reached Wheaton College, a private Christian school outside of Chicago, Jamie was nominated to implore me not to talk about condoms. They were afraid of offending the students. Naturally, I wasn’t having any of it.

“These are my people, Jamie,” I said. “I am comfortable with evangelicals. I grew up part Pentecostal.” So I took the stage and shouted, “They don’t want me to talk about correct and consistent condom use! They don’t trust Christians to get it!” The kids were cheering. It was great. They let everyone know they could be devout Christians at a sectarian college and still accept the A, the B,

and

the C of HIV prevention: abstinence; being faithful and delaying onset of sexuality; and correct and consistent condom use with every sexual act. (Eventually, I would add my own D: delay of sexual debut, especially important for girls, who are so often preyed upon by older men.)

Kate Roberts joined us in Chicago, as planned. I liked her immediately. She was an elegant Englishwoman in her mid-thirties, with chestnut hair cut in a chic bob and a graceful carriage that radiated energy and purpose. In fact, I liked her so much that I didn’t mind that the first thing she said to me in our get-to-know-you moment was, “I have to tell you, I loved you in

Pearl Harbor.

” Then, after I pointed out that I was not in that movie, she continued to insist that I was. I thought:

Wow, I think I’ve met my match in this woman!

It’s another thing we still laugh about.

I didn’t realize that Kate had actually come to audition me for the job of global ambassador. Just as I had tried to perform due diligence by researching PSI and YouthAIDS, she in turn wanted to observe me in public and see how I handled the material. Kate accompanied me to the next event, which was a meeting in a South Side Apostolic Faith Church where each member of our group was going to talk to the congregation about HIV. After listening from the sidelines to Agnes’s story, I confessed to Kate how inadequate I felt. I had so much feeling and intensity, but I felt like a bit of a fraud and was scared I’d do something unhelpful. “I don’t have any experience in the field.”

“Then let me tell you a story,” said Kate. She described Mary, a prostituted woman who made her living in a squalid Kenyan brothel. Mary had been hired by PSI/YouthAIDS to be a peer educator for other exploited women, teaching them how to protect themselves and their clients from the spread of HIV. Kate told me that PSI/YouthAIDS tries to change risky behavior and empower people to use condoms—female condoms for exploited prostitutes and male condoms for their clients. But Mary gave Kate an example of the violence that goes on in the highly dangerous world of forced paid sex and how treacherous it can be to try to be safe. One night Mary was trying to persuade a client to use a condom, but instead he pulled a wrapped piece of candy from his pocket and jammed it into her mouth. “Chew!” he ordered. So she chewed the wrapped candy as he glared at her. “See!” the client hissed. “That’s what it’s like using a condom.”

And then he beat her to a pulp and raped her.

I turned away from Kate and walked to the microphone. I was enraged by what I had heard and a powerful sense of humiliation engulfed me. Time and space dissolved, and somehow Mary was with me as I boldly expressed her righteous indignation in America, an anger Mary, as a disempowered African woman, is denied. These were the first, lurching steps I took toward a purpose I could suddenly feel, even if I couldn’t wholly understand it yet: My role was to share the sacred narratives of people who are ignored by this world, to make them real to powerful governments and ordinary citizens who, rightly or wrongly, will listen to me. And it was my own background that modestly qualified me for this newly revealed mission—not just the fame that had accompanied my acting career, but more meaningfully, my very own shame, my very own righteous anger, my very own journey as an abused and neglected girl. While my circumstances were obviously different, I identified powerfully with Mary’s

feelings

. It would take several countries and many brothels and slums to piece it together, but in offering myself to my newfound brothers and sisters everywhere, I met an additional, equally precious child: the girl I had once been.

After the meeting, I sat in a pew. I was overwhelmed by the power of being in a charismatic church with a predominantly African-American congregation that was really “getting it”—recognizing that gender inequality, poverty, exploitation, preventable disease, and all the human rights violations inherent in the HIV emergency are connected to their own everyday lives in America. I had been in a fact-finding, making-sense-of-it-all mode since the beginning of the tour. I was being serious and professional and was intent on doing a good job. But now I was in a safe, faith-filled place where I could give in to all my feelings, and I began to feel the presence of the Holy Spirit. I started to sob. The harder I cried, the more strongly I felt the presence of God. This is an experience I always cherish, one that brings down all my walls and affirms and validates my values—it is a time when I feel so vulnerable and raw, yet totally safe and protected, when I seem to become part of an unfathomable whole. I cried and cried. I can never control what happens when the Holy Spirit comes, and it’s futile to try! I was sitting near Bono, and he gave me an empathetic look that said, “Oh, there she goes!” Kate saw this, too, but didn’t seem concerned. After a while, I pulled myself together and got back on the bus. I was ready for the next step.

“Where do we go first?” I asked Kate.

Chapter 6

OUK SREY LEAK

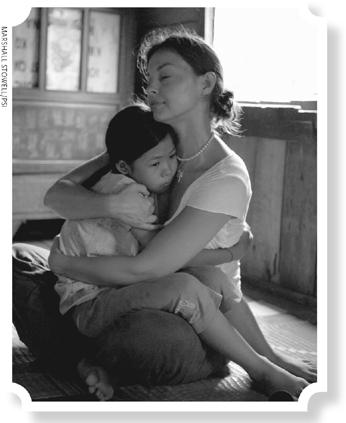

Ouk Srey Leak, the orphan who let me love her.

When your face

appeared over my crumpled life

At first I understood

Only the poverty of what I have.

Then its particular light

on woods, on river, on the sea,

became my beginning in the colored world

—YEVGENY YEVTUSHENKO

, “Colours”