All That Is Bitter and Sweet (11 page)

In the short term, my brief stay in the hospital was a salve. As soon as an IV was in my arm, my fever came down and I started feeling better—although I think my relief was related more to being out of what was for me a toxic environment and having my mental illness acknowledged without judgment. The nurturing care the nurses gave me was profoundly moving. They weren’t treating me as if I were crazy; they were just doing what nurses do—running the bath, checking on me, being kind. I needed that. But I did continue to have spells while in the hospital: emotional meltdowns and impulses to self-harm. I kept them secret from the nurses, because I wasn’t in the habit of identifying and talking about these things with anyone yet, and I was scared they would reject me if I seemed too crazy for them. I was afraid of being in trouble for having an emotional problem.

During all this, I was still hoping to attend President Clinton’s second inauguration in January 1997, to which I was invited because I had campaigned for him and introduced him when he spoke in Kentucky. I even tried on Armani gowns in the hospital while still attached to an IV pole. It was an unrealistic wish.

When I felt well enough to leave the hospital, I took the advice of the therapist friend and moved out of my mom’s house. I rented a beautiful cottage on a farm near Franklin and started taking better care of myself. I had a lot of massages, practiced yoga and breathwork and meditation. One particularly special girlfriend called from L.A. every night at bedtime, knowing that was always the hardest time of day for me. Although I didn’t yet have all the tools I have today, I was instinctively working through my anger to access the pain and grief that was beneath it. And very slowly I began to heal.

In March I made my first trip to Los Angeles in many months. My interest in the outside world was returning and I felt a little stronger emotionally. Although I was still exceedingly vulnerable, it was time to begin reengaging with my professional life after a long winter of depression-induced hibernation. I accepted an invitation to

Vanity Fair

’s Oscar party, thinking that could be a good way to dip in a toe. Valentino came to my hotel room to tie the sash on my dress, and I felt special as I walked out the door and faced the bank of cameras on the red carpet. But at the party, I soon found myself drinking coffee to stay awake. I felt lonely and isolated in a big, festive crowd and decided to leave early. I was actually trying discreetly to slip out when an exuberant friend led me across the room and sat me down next to an elegant man with a strong presence and a shock of gorgeous wavy black hair: Bobby Shriver.

We sat there a bit and chatted. He was drawing little sailboats on his paper napkin, and I assumed that he was one of the idle rich. So I asked somewhat facetiously, with a little aggression, “So do you have a job?’

Bobby was a lawyer, journalist, businessman, and record producer who made Christmas records with artists like Bono, Madonna, and Stevie Wonder to support the Special Olympics, the spectacular organization founded by his mother, Eunice Kennedy Shriver. (His father, Sargent Shriver, had started the Peace Corps, and his sister, Maria, is a superb journalist.) After he ran down the basic résumé, Bobby asked me, “What’s

your

job?”

I said, “Well, acting is my job, but it’s not my vocation.”

“So what’s your vocation?”

I was not up for being coy and could not tolerate what felt like nonsense. Depression can be good for me that way: It helps cut the bull and strips me down to the essence of what matters and what is worth living for—although I sometimes lack the flexibility of choosing the right time and place to share such things. I looked this stranger in the eye and said, “My vocation is to make my life an act of worship.”

He pushed back from the table, excused himself, and went to the bathroom.

I was thinking to myself,

How’s that for an Oscar party line?

But it was the absolute truth, although perhaps more of an aspiration than a reality at the time. Even if I wasn’t doing social justice work, I was always praying, reading, writing, and trying. God was the central fact of my life, the principle around which I tried to organize everything. Bobby later told me he didn’t really have to use the bathroom; he had to compose himself because he was so floored by my response, which he thought was the perfect answer. He came back to the table, and we talked some more about what the God of our understanding might be calling us to do, and service as an expression of God’s love. By the end of the evening we knew we had made a deep, lifelong connection. We tried dating for a short time but found out we were better at being spiritual siblings. We met at yoga classes, and he took me to his Exeter class reunion. When Papaw Ciminella, who was a lifelong racing enthusiast, was dying, I left the hospital long enough to attend the Kentucky Derby with Bobby. When my grief suddenly poured out of me in between the social events of the day, Bobby ended up sitting with me patiently, holding the space for me as I keened. He proved to be a perfect friend and always encouraged me to give more of myself to the sick and the suffering, emphasizing that such work is not about pity, it’s about justice.

Chapter 5

MAKING OF A RABBLE-ROUSER

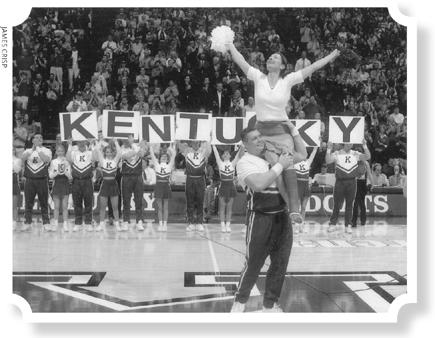

Making the

Y

in

Kentucky

(with a broken ankle) while watching my alma mater’s men’s basketball team.

A man wrapped up in himself is a very small man.

—

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

’ve always had an intense sense of righteous indignation and an urge to speak for the voiceless and oppressed—likely because I felt so invisible and invalidated when I was a child. I could never stand to see anyone being abused, especially my sister, whose childhood was undoubtedly as difficult as mine, although in different ways.

’ve always had an intense sense of righteous indignation and an urge to speak for the voiceless and oppressed—likely because I felt so invisible and invalidated when I was a child. I could never stand to see anyone being abused, especially my sister, whose childhood was undoubtedly as difficult as mine, although in different ways.

By the time I was in college, I was ready to become a full-fledged social activist. At the University of Kentucky, I completed a major in French, four minors, and the full honors program curriculum—but my undeclared major was rabble-rousing, or at least as much rabble-rousing as one could do and still belong to an old, elite social sorority. Tapping into that legacy grounded me in a meaningful way. And I loved the idea of living in the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority house, a beautiful southern home with nice furniture and wallpaper, located in a separate, elegant quadrant of the campus. I moved into a four-woman room and relished the sense of camaraderie.

I was a smart kid who loved learning and earned mostly great grades but because I had attended thirteen different schools during my scattered childhood, I was unevenly educated when I arrived at college. At first I was unsure of myself. I had been told I was smart and special, and I was expected to be fairly perfect and to represent my family in and out of school with charm, poise, consistency, and ease. But I was pretty confused about my alleged gifts: Was I smart? Was I gifted? Was I even capable? One of the things that really threw me was that in my little girl’s mind I had somehow made up that if one were smart, everything should be effortless. If one were talented, one should not have to try hard. As a result, even when I made good grades in high school, I hid a haunting fear that I was worthless and a fraud. But within the “loco parentis” of the campus and my sorority, I soon felt safe enough to be myself.

I attacked academic life at UK in a way that viscerally sparked my mind, spirit, and emotions. I could feel new thoughts germinate and grow, I could feel areas of my brain expand and crackle with earnest life and confidence where previously there had been only fear, guilt, and debilitating shame. In the most meaningful way, I grew up. I discovered the fearless scholarship of gender studies, the enthralling explorations of anthropology. I was lucky enough to gravitate toward spectacular professors, especially feminist ones, who revolutionized my life with their teaching and revelations. I studied the philosophy of agriculture and discovered that despite famines there was never a food shortage, just problems of distribution, political will, poor governance, and apathy that caused millions to starve. I recall sitting at a table and studying so hard, reaching for new ideas, making intuitive connections, that I could feel things fire in my brain. I was turning my gaze both inward and outward; claiming through deeply personal experience citizenship in a much larger world; and slowly starting to recognize my responsibilities and interconnectedness with suffering people everywhere.

Living away from home and family, I was, for the first time in my life, mostly happy. At the student center, I joined every progressive cause I could find, from Amnesty International to the NAACP. I listened, crying, to LPs, brought out of South Africa by friends, of Archbishop Tutu’s Christian antiapartheid message, and I organized demonstrations against my university’s ongoing financial association with apartheid. I led a campus-wide student walkout of classes to protest a university trustee’s use of a racial epithet. I uncomfortably began to face my government’s deep enmeshment with dictators and complicity with gross human rights atrocities worldwide, especially in Central America and sub-Saharan Africa.

The driving urgency of songs on U2 albums like

Boy

and

The Unforgettable Fire

fueled these first forays into human rights and peace activism. It was through their liner notes that I discovered Amnesty International and leverging art and pop culture to protest human rights abuses. When

The Joshua Tree

came out toward the end of my freshman year, I was captivated along with the rest of the world. But I also discovered a tangential personal connection to the band.

Rolling Stone

magazine put U2 on the cover that week, and it was noted in an interview with the band that they were fans of my mother and sister. In particular, drummer Larry Mullen Jr. said he was digging the Judds’ music, playing “Rockin’ with the Rhythm of the Rain” in his car. I was instantly extremely cool around the Kappa Kappa Gamma house.

I traveled to France the summer after my sophomore year with some classmates and a professor to spend six weeks immersed in language, culture, and history, then stayed on “to find myself,” as I told my mother. When I found out that U2 would be playing the Hippodrome de Vincennes, I introduced myself to U2’s management as Wynonna’s little sister, and they kindly gave me a backstage pass. Even though I was comfortable in that milieu from my upbringing, I was swollen with excitement at being backstage. I was nineteen years old and on my own, and Bono, Larry Mullen, all the band members, their spouses, and the crew embraced me. I look back now and can only thank God for putting these people, who have had such a defining, spiritual impact on me, into my life at such an impressionable age. At President Obama’s inauguration, Larry’s wife got to reminiscing about what a little girl I was when she met me. That the same girl had since grown up to host the Inaugural Purple Ball and embrace the world is, in part, a testament to my friendship with the U2 family.