All That Is Bitter and Sweet (8 page)

Best of all was when Mamaw and I would gather up all the soft pillows from the bedrooms and make a nest on her bed. She would cut off the air-conditioning and open all the windows—mountain all the way, she despised air-conditioning, as do I today. Cuddling on her bed, we would play cards, giggle, sing ditties, or just listen to the katydids chirping in the Kentucky twilight. That downy, soft bed was the high altar of my childhood.

Until Nana and Papaw Judd divorced when I was eight, they lived together in the beautiful, classic American house that was filled with generations of smells, love, and comfort. It was roomy and broad, with a front porch complete with a swing I loved, beveled glass windows, a fascinating attic, an alluring basement, and secret places for imaginative children to play. The drawers were still filled with report cards, marbles, toys, and drawings belonging to Mom and her siblings, their books on the shelves. The yard was enthralling, and I often spent hours under the low-hanging limbs of soft evergreens, making a world under there. There was an air of sadness in the house as well, because of the lingering memory of Uncle Brian and the terrible wound his death left in the family, a wound that Nana and Papaw Judd’s marriage ultimately did not survive. Nevertheless, I have wonderful memories of that house, which I regard practically as a member of the family.

The most fun was when Papaw Judd took us way out to the country to visit his family’s home place or to spend time with his sister, Pauline. I worshipped Great-Aunt Pauline, who was a sophisticated, educated woman with a sensitive nature who chose, for love, to live an old-fashioned lifestyle on a poor farm in rural Kentucky. She and Great-Uncle Landon lived in what was to me a gorgeous mountain farmhouse filled with practical furniture that today would be rustic collectibles and decorated with delightful old flowered wallpaper. By the 1970s they had some electricity and one big black telephone in the kitchen, but they still used an outhouse and drew water from a well that had to be boiled on an iron wood-burning stove for cooking and bathing. (It is this home that the press has often conflated with my other homes, writing that I grew up dirt poor without electricity and plumbing.) Great-Aunt Pauline always had at least a dozen dogs on the property, all named after Democrats. She was an amazing cook; everything was raised on the farm or traded for. I remember the oilcloth tablecloth on her kitchen table and the incredible dinners (that’s the noon meal) she would put out. If I could magically have any meal in the world, it would be her fried chicken dinner, buttermilk biscuits, and homemade blackberry jam. She worked from sunup until sundown, completely present in the life she chose. I spent my afternoons on her screened-in porch, just watching, and content by proxy, seeing how much Papaw Judd clearly loved being there, using his pocketknife to cut fresh cucumbers into slices he would salt and share with me.

These are my most precious memories, and I have dreams about them to this day. All children deserve to be cherished in this way. I was lucky to have this reserve of memories to cling to during the rest of the year, of a place where there was no neglect, no fighting, no drug and alcohol abuse to witness, no worries about being anything but a child, where it was okay to be vulnerable and have little-girl needs. Those recollections sustained me and probably saved my life when I was in so much despair that, even as a young child, the only way I could think to make the ache in my heart lessen was to die. They are also why I understand profoundly that every child needs a safe person and a haven. I continue to draw on the unconditional love I was given during those times, both as an essential resource for myself and as a source of love that I am able, when I am at my best, to give away in incredible abundance.

Chapter 3

BUTTERMILK AND MORNING GLORIES

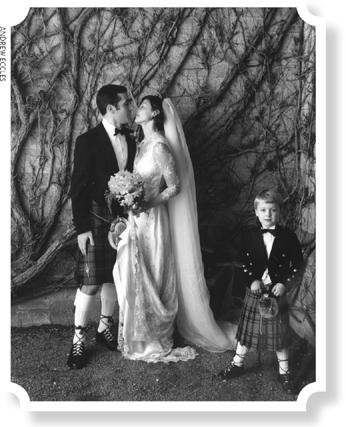

Our wedding day at Skibo Castle in the Scottish Highlands.

I never spoke with God,

Nor visited in heaven;

Yet certain am I of the spot

As if the chart were given.

—

EMILY DICKINSON

, “Time and Eternity, XVII”

he two-hundred-year-old farmhouse where my husband and I live in rural Williamson County, Tennessee, pays homage to the spirit of safety and graceful domesticity that I remember from the beloved sanctuaries of my childhood. The countryside where we live is impossibly lovely, with green rolling hills, open pastures, creek-cut hollows, artesian springs, and beguiling examples of American farm and cottage architecture set along the winding roads. It’s real, not kitschy and packaged, with old farming families and hillbillies living alongside music-business money, poverty mixed with comfort.

he two-hundred-year-old farmhouse where my husband and I live in rural Williamson County, Tennessee, pays homage to the spirit of safety and graceful domesticity that I remember from the beloved sanctuaries of my childhood. The countryside where we live is impossibly lovely, with green rolling hills, open pastures, creek-cut hollows, artesian springs, and beguiling examples of American farm and cottage architecture set along the winding roads. It’s real, not kitschy and packaged, with old farming families and hillbillies living alongside music-business money, poverty mixed with comfort.

When I began to dream of making myself a home I could live in for the rest of my life, a home that would shelter me longer than anywhere I had ever lived before, this was the place the fates seemed to choose for me. In 1993, after the house I was renting in Malibu was destroyed in a wildfire, leaving me stranded, my sister gave me a fabulous fixer-upper of a farmhouse on a piece of her land. I was grateful for her kindness and thought nothing of forgoing Los Angeles to settle into the rural, bucolic life I so dearly love. The property was the original homestead of the Meacham family, who once owned the large farm from which my mother and my sister bought acreage whenever they could afford it. My sister and her kids live within walking distance of my back door, while our mother and her husband of twenty-five years, Larry Strickland, whom we call Pop, live down the road. My father now comes for long visits with his creative, lovely wife, Mollie Whitelaw. Even though I’d spent so much time apart from my family when I was growing up—the chaotic, painful separations of my childhood continued long after the Judds settled in Nashville and became stars—we’re still in one another’s lives, for better or worse. Mostly better. Along the way, these bountiful Tennessee hills have seeped into my soul and given me a home where my heart can finally be safe and find some rest.

It took years to restore the old Meacham place to its former beauty. I pulled from deep memories of comfort, associations of unconditional love, rural living, and elegance. To begin, I jotted down simple notes that became my guiding document, things like “Great-Aunt Pauline and Great-Uncle Landon’s farm; the old home place on South Shore; Nana’s small print floral sheets; quilts; soft, faded velvet, old-fashioned flowery wallpaper; chenille blankets; Mamaw and Papaw’s dining room table; beautiful trims; crafts from Berea.” I had my work cut out for me. The house had only one small bathroom, put in during the 1960s by a local vocational school’s student project. I uncovered and restored five fireplaces and other old-fashioned features that made it so wonderfully period. I salvaged beaded board, leaving splotchy layers of beautiful old hand-painted wallpaper exposed. The onetime smokehouse was converted into a ridiculously charming guesthouse.

My other guiding principle was to make the house completely open to the outdoors. Windows were enlarged, skylights installed. I added floor-to-ceiling glass to the screened sleeping porch, the most lived-in room in the house, from which we look out on wooded hills folding into pastures of native grasses (which I constantly battle my sister’s farm manager to keep from mowing!).

All of my life I’ve drawn solace and inspiration both from wild spaces and lovingly tended gardens. Fern-shaded creeks, fields of Queen Anne’s lace, hills covered with bluegrass, dogwoods, and redbuds—a childhood landscape that imprinted on me as a pastoral ideal and stirs in me the most bittersweet longing.

In restoring the land around my farmhouse, I wanted to re-create my own memories while honoring the history of the place. I replanted the gardens with what I knew various Meachams across the generations had grown, which meant native species that flourish. Morning glories and moon vine cover my porches. Old varieties of hollyhock lean against columns, fences, and gates. Salvia, hostas, zinnias, and pretty much everything else you could think of grow somewhere in my garden, offering riots of color. I went rose mad in London filming

De-Lovely

and have dozens of bushes to prove it. I planted over thirty thousand daffodils—my ongoing gift for two-year-old me, my child’s eyes filled with shy wonder in a faded photograph, admiring a daffodil in Nana and Papaw Judd’s garden forty years ago.