All That Is Bitter and Sweet (31 page)

Back at the hotel, I soothed and calmed myself with normal, stable routines, such as hand-washing my things in the tub. I skipped my stained, caked linen pants, though, and decided I’d retire them dirty with a few other special things I kept in my closet, such as the sandals I wore my first summer in France and the sneakers in which I survived the ashram’s hikes. After so many years of following the liberation struggle, my pants were my own little piece of Soweto’s soil, sun, and soul.

It was finally time to go home. I’d had twenty days in Africa, and provided I had some sleep, I felt I could easily carry on with the work. But I wanted to be at Dario’s race that weekend. His energy beckoned me, and I couldn’t wait to connect with it. I was set to arrive at the track just in time to hustle out to the grid for a bad-airplane-breath kiss before the green flag.

During the transatlantic flight, I discovered an entire Joni Mitchell CD on the in-flight entertainment. I covered my head with my blanket and sang along with “Carey” as loud as I could without attracting attention. Then I listened to “California,” and the earphones made her so present to me, and therefore me so present to myself. I became the person I was when I was eight and “Carey” was my favorite song, or who I was when I was six and I lost my first serious fight, which happened to be with my sister, over the order of verses in “Twisted,” discovering in spite of my fierce conviction that I could be dead wrong. Or who I was in college when I played “California” on my radio show, or who I have been every time I felt the rapture of the rhythm of “Help Me” or reminded Sister on the phone of all the lyrics to “You Turn Me On I’m a Radio,” or who I was each time I drove to the theater while doing

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

, swept away by her brilliant orchestral revisitation of her old material. I felt all I had been, and all I am now, and it was so sweet and so

here

, a beautiful, almost unbearably exquisite

here

, my arc and my life, and the women who have entered it, oh, my hand on Nini’s belly, Sahouly’s incandescent smile turning toward me like a rising half moon, half radiant, half shy.…

“Amelia” affected me deeply tonight:

Me, well, I’ve been to Africa.

Chapter 12

BUMPING INTO MYSELF

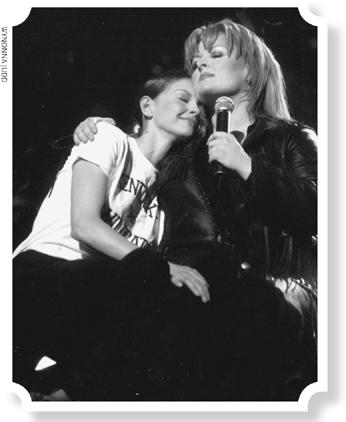

My extraordinary big sister, Wynonna Judd. Of the many gifts she has given me, introducing me to recovery is the greatest.

The spirit is never at rest, but always engaged in progressive motion, giving itself new form.

—HEGEL

, Phenomenology of Mind

n the months after my return from Africa, I should have felt on top of the world. The outer form of my life seemed perfect; I had basically done everything I had hoped to do. My film career was still thriving, and I gave performances of which I was proud in a couple of creative, inspired independent projects. The trip to Africa was a huge success, including

n the months after my return from Africa, I should have felt on top of the world. The outer form of my life seemed perfect; I had basically done everything I had hoped to do. My film career was still thriving, and I gave performances of which I was proud in a couple of creative, inspired independent projects. The trip to Africa was a huge success, including

Tracking the Monster

, the VH1 documentary shot in Madagascar about PSI’s Global Fund–sponsored programs, which was broadcast in eighty-one million homes worldwide, received great reviews, and won an array of awards. In June, I was invited to testify about the AIDS crisis before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in Washington, D.C. I told the committee members that the fight against the HIV/AIDS pandemic was indistinguishable from the fight for gender equality, that there was nothing more important in the struggle against this virus than to urge all societies to reject violence against women and any social norms and cultural practices that cause girls and women to exchange sex for economic survival. I also spoke about PSI’s mission to a roomful of reporters at the National Press Club in Washington, where I looked in awe at the twentieth-century headlines hanging from the venerable club’s walls.

I was finally using my voice to speak out on the political level for the voiceless millions whose lives are affected by the policies being shaped in distant world capitals. Through my work with PSI and other organizations, I was earning a seat at the table, not for me, but for Ouk Srey Leak, Shola, Sahouly, and the women of Soweto whose stories had moved and inspired me to change my life.

My confidence and the smooth exterior of calm and professionalism I presented to the world, however, only disguised the growing chaos I felt inside me. On trips to see grassroots programs, I was focused and single-minded, the harrowing feelings externalized by being in settings rife with egregious examples of trauma and grief. But at home, there was nowhere outside of myself to direct and metabolize my own pain. A familiar, gnawing emptiness haunted my days and nights. I could feel the trapdoor underneath me opening again. I was having trouble modulating my behavior; I’d swing back and forth between being paralyzed and overdoing whatever I undertook. I might be able to confidently lobby archconservative Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell in his chambers, but I couldn’t seem to manage the simple task of finding a comfortable chair for my writing desk. That summer I decided to reorganize our library to accommodate Dario’s ever-increasing haul of trophies, and once I started, I couldn’t stop. I began sorting through all the unsolicited gifts that were piling up around me, writing thank-you notes and deciding what to give away, then alphabetizing all the books within genres, steaming with resentment that I “had” to waste my time processing stuff people randomly sent me that I hadn’t wanted in the first place. I could become irritable and unreasonable without knowing it and was unable to place things in their proper perspective.

I was also concerned about some frustrations I’d had during the making of

Come Early Morning

and a few months later on the set of

Bug

. It wasn’t anything awful, just work relationships that became muddled because I couldn’t seem to make my assistants understand what I was saying. I wondered if I was expressing myself poorly or if they simply weren’t hearing me. I concluded I was the common denominator and that I needed to take a look at my own behavior to tackle these ongoing communication problems.

I had embarked on a program of radical self-investigation through yoga, where teachers like Seane Corn showed me how a practice could heal on the emotional—not just the physical—level. Now I decided to augment it with a series of intensive therapy sessions with a remarkable and gentle counselor and life coach named Ted Klontz, a PhD with wide-ranging experience who was referred by an admired friend. She had said, “I trust Ted with my life.” Her endorsement made an indelible impression on me, as I had the sense that my own life might be at stake—and that I might uncover more than a simple failure to communicate.

The approach Ted began using with me is called “motivational interviewing,” which would rely upon identifying and mobilizing my own intrinsic values and goals to stimulate my desired changes in my behavior and improvements in my feelings. In our conversations, my motivation to change would be elicited from within me, and not imposed from without. Ted guided me as we discussed relationships and behaviors, past and present, validating my reality, gently pointing out my contradictions, letting me catch my own ambivalence, and make my own discoveries. Ted referred to this as helping me “bump into myself,” and it felt more organic and transformative than anything I had ever done before.