All That Is Bitter and Sweet (58 page)

As we said our goodbyes, members of the costume department brought us gifts, rows of glass bracelets and dangly earrings worn by the film’s stars, wrapped in shiny paper. Kate and I oohed and ahhed. I asked them lots of questions. They said they worked nineteen hours a day, slept on set, and had no union. I was shocked. The unfairness and inequity and brutal poverty of India were really beginning to wear me down. Despite the victories of the afternoon, I was finding myself increasingly pissed off at this country. And at my next activity, I was about to become a whole lot angrier.

Chapter 19

A HOLY MESS

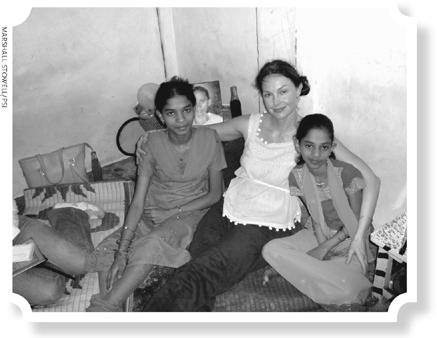

Neelam and Komal, the orphans who asked me to adopt them.

Seek refuge in the attitude of detachment and you will amass the wealth of spiritual awareness. The one who is motivated only by desire for the fruits of their action, and anxious about the results, is miserable indeed.

—Bhagavad Gita,

verse 49

atasha sat in a large chair in the production office, looking very small, frail, gorgeous, and groomed. Her hair was long and lovely in a Veronica Lake–type wave. Her English was fairly good, and she was soft spoken yet clear. The camera was set up to protect her identity, and in postproduction her voice would be modified, too. One of the documentary film’s producers, posing as a sex client, had put feelers out to find a “high-class call girl” I could interview to show how HIV/AIDS is spread to the upper reaches of Indian society by prostituted women who service wealthy clients. That was the story we were looking for; what we found out still gives me nightmares.

atasha sat in a large chair in the production office, looking very small, frail, gorgeous, and groomed. Her hair was long and lovely in a Veronica Lake–type wave. Her English was fairly good, and she was soft spoken yet clear. The camera was set up to protect her identity, and in postproduction her voice would be modified, too. One of the documentary film’s producers, posing as a sex client, had put feelers out to find a “high-class call girl” I could interview to show how HIV/AIDS is spread to the upper reaches of Indian society by prostituted women who service wealthy clients. That was the story we were looking for; what we found out still gives me nightmares.

When Natasha arrived at the address her “escort service” was given and discovered what we were really after, she told us she was a full-fledged sex slave and her life would be at risk if her owner discovered what she was doing. But she wanted to tell her story, if only to help others in her predicament. And we had to pay her fee—12,000 rupees, about $270 U.S.—so that nothing looked odd and she’d have the right sum of money to give her pimp.

When we settled in, she told me she was about twenty-one or twenty-two years old (many Indians can only approximate their age) and had traveled to Mumbai when she was about eighteen to visit some relatives. Her luggage was lost and there had been a lot of confusion about her arrival. She managed to end up at a girlfriend’s apartment to spend the night while she sorted things out. Her friend was going out for the evening and invited her; she was happy to tag along. The friend took Natasha to a hotel. They went up to a guest room, where a man was waiting. The friend smiled and left the room. To her bewilderment, Natasha realized she had been left there to have sex with the man. Fearing physical violence and feeling trapped with no way out, she did. When the man let her go, she went downstairs. Her friend was waiting. She slapped her face. The friend said, “Welcome to the garbage bin.”

In a disastrous piece of timing, the relatives she had been looking for had tracked her down through her friend just as she was leaving the hotel. They put together why she was at such a nice hotel and immediately disowned her as a whore. She had nowhere to go but back to her friend’s apartment, where her fate, trapped in sex, was sealed. Simultaneously, her relatives were spreading this information back home. She was swiftly, irrevocably ostracized by her family there—even though they took the money she sent them.

Natasha told me she was in a hell she could not escape. Her story is a complex puzzle, a combination of truly being trapped

and the commensurately powerful perception of being trapped

. That makes it hard to describe; it also makes my dismay deeper. Here are some questions I asked and her answers:

Why didn’t you then, why don’t you now, just go to the police and explain what happened? Why don’t you tell them about your life now?

“They would be the first to rape me,” she said with a sad smile. “Then they would simply hand me back over, and there would be more trouble when I was returned.”

Why don’t you secretly, however long it takes, stash away a little bit of money and just sneak away, go somewhere else in India, start over? (Yes, I asked a lot of embarrassingly dumb questions from a Western perspective … but I think we all would have.)

“Wherever I go, I will always be

this.

” She sighed. “I will see a former client who will reveal my past, and I will never be accepted anywhere as anything but this.”

This was so troubling. In a country of nearly 1.2 billion, she had sufficiently internalized her victimization and her boss’s fear tactics to believe that wherever she might go on the subcontinent, a former client would identify her and she’d be put back into forced sex. And it might be worse than her current situation. Even though her client’s large fees are immediately taken away from her, she holds back a little to send to her home village to support eleven members of her extended family, the same remorseless family that shunned her. Because they “depended” on her, she said she had to continue earning such high fees. She was trapped by her own mind and didn’t even know it.

Do your clients use condoms?

“Yes, the boss makes sure they understand they must. I am tested for HIV every alternate month.”

Ah, yes, it’s not called organized crime for nothing. A healthy prostitute is a better earner.

Has anyone among you tested positive?

“Yes.”

What happened? Did she receive treatment?

“I don’t know. She disappeared.”

Where do you think you will end up? Is it your fear that when you begin earning less you’ll be dumped at a brothel in Kamathipura?

“I can’t think about that,” she said, her face flashing blind panic. The question so terrified her, I instantly regretted asking it.

When I asked her questions about her daily life, her answers were even more chilling. Natasha said she lived in a three-bedroom apartment with ten others, all of whom shared her predicament. She is on call twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. She never knows when the call will come; she lives knowing at any second she will be sent to have sex with a strange man, and she must do whatever, however grotesque, painful, and degrading, he wants. Her owner is someone she has never seen. In a perverse twist on

Charlie’s Angels

, she hears his voice on the phone as he bosses and threatens her. The pimp is the day-to-day manager of her life, checking on her, spying, supervising, and collecting money. Her clients include Indians and foreigners. I asked her if she had been to the Taj, my hotel, and she smiled. “Oh yes, many, many times.” I felt sick.

Sensing the destroyed condition of her soul, I flailed for something, anything, positive to talk about. “Your English is so impressive, Natasha. You speak wonderfully. I bet you read very well.” She said indeed, she did read some. When I asked what she might envision herself doing as a career, she told me she had long ago dreamed of becoming an Ayurvedic doctor, but insisted that this was now impossible. She did, however, try to surreptitiously teach the others, the little ones, at the apartment to read so that maybe someday they could do something different.

“The little ones?” I asked, a new sickness rising in me.

“I am the oldest,” she said. “The youngest is about fourteen.”

What? How long has she been there?

“She was eleven when I arrived three years ago. The others are fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, around there.”

What does one say to that? How does one react? My time with Natasha was coming to a close. She couldn’t be late without arousing suspicion. The next part for me was incredibly emotional. To know she was walking out of that room and back into her life was a pain the likes of which I have felt only a few times in my life, pain like walking away from forty orphans in a well-meaning but underfunded crèche in a South African slum. It was just so wrong, so very, very wrong. I pulled her close to me and held her and tried to burn myself into her eyes.

I said to her, “Will you believe there is hope for you?”

“No.”

“Natasha, can you believe, then, that I believe? When you are completely hopeless and despairing, will you remember me,

can you believe that I believe

?”

She broke down. “Yes. I will try, I will try. I will try to believe that you believe.”

The time for which we had paid was up. She was crying as she hurried out the door. As a team we raged, sobbed, planned, plotted, and despaired. With Papa Jack guiding us with his New York police and FBI experience, we tried frantically to sort out ways to reach Natasha again, to rescue the children. Every idea was a bust, as each one, given the vulpinic efficiency of organized crime, led to potential danger for Natasha. Their network is so vast, so thorough, so complete—and girls and women are so disposable. It is unlikely we will ever find her. She and the other slaves of her type are a mysterious, inaccessible component of prostituted commercial sex. But we will never forget her. And every day, every minute, every breath, I bless her. I still believe, Natasha, I still believe.

The evening with Natasha made my meeting the next day harder. We passed again through rows and rows and rows of houses, many with modest religious icons or now dead flowers over the crumbling portals, crammed full of people going about their daily lives. In one of these houses Neelam, fourteen, and her sister, Komal, twelve, were waiting for me in matching yellow saris. They were AIDS orphans who lived with an aunt in two low-ceilinged, windowless rooms. Both girls were very small and thin, with long dark hair. Komal’s was lustrous and smooth, Neelam’s was rough, coarse, dry. I wondered if it was from malnutrition. The children each took a hand, brought me in, sat me down. They were eager yet reserved. Indian women sit alongside one another, knees touching, arms draped across each other’s legs. I had picked up on this and gratefully snuggled into a comfortable position with these precious girls. They would never sit in my lap, but they did sidle up to lean on me and let me love on them.