All That Is Bitter and Sweet (61 page)

The organization, which was started by a group of street children—again, the real experts—runs a drop-in center that provides a safe space where the boys can sleep and spend time during the day. It teaches personal hygiene, feeds them, begins literacy training, and offers spiritual direction. They meditate in the mornings, pray before meals. Some of the boys were AIDS orphans, others ran away from abusive homes. I held a ten-year-old and a four-year-old on my lap, darling little things, and we talked about everything under the sun. Both had escaped abuse, preferring the mean streets to the cruelty at home. The older one had been raped about five times. It was unbelievable that he was so honest with me. (I began to realize some of the gender differences within the sexual exploitation of children. Girls are often kept captive and used chronically; boys are used episodically by occasional predators.) I liked it best when we talked about safe touching. I said one should ask first and remember that everyone has the right to say no, and we should each respect another’s “no.” The little one had been taken in by the center within two days of arriving at the rail station. The older one had been addicted to huffing paint fumes, something common among urban, traumatized youth. Often it’s done initially to ward off hunger, but the high also becomes part of the appeal, a way to numb the pain of reality. Amazingly, I could share some simple concepts with him. After we discussed it, he said he believed he was powerless over huffing, that it made his life unmanageable, and that there was a good and loving God, and he could ask his God for help refraining from huffing, one day at a time. (Of course, I don’t think he’ll be permanently fixed, but maybe it’s a tool that will give him relief from time to time.) I asked them if in honor of the special time we spent together they’d look out for one another after I left. Still on my lap, they beamed at each other, squealed “yes!” and showed me how they were going to hug and hold hands.

I wandered around the neighborhood, going deep into the thicket of provisional dwellings, imagining life here day in and day out. I was sitting in a makeshift shanty, on the bare dirt underneath a scrap of canvas, when I heard a kitten crying plaintively. I panicked. It freaked me out so deeply, I knew I had to flee or I was going to stand up and rip the slum down to

find that cat right now now now now

, or I was going to freeze and sit there and listen to this little mewling sound and completely

lose my mind

. I was afraid I was on the verge of going emotionally somewhere far, far away and not coming back. My brain was flooded. Of course, I was transferring the grief of ten thousand and my own triggered, vicarious trauma onto that one kitty cat, and I had just enough sense left to know it. Somehow I stumbled to my feet and started walking away. And then the children of the shelter brought me back to this world. They surrounded me to say goodbye and sent me off with an echoing chant that sounded like bells in the distance:

Oom shanti shanti shanti … oom shanti shanti shanti …

In the car, Marshall asked me if the smell of poop had bothered me when the boys were on my lap. “No,” I said. I hadn’t even noticed.

Mother Teresa of Calcutta, when awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, was asked by a journalist what she intended to do with the million-dollar gift.

“Feed the poor people of India,” she said.

“You couldn’t possibly!” the journalist cried. “Feeding the poor people of India would cost far more than that!”

“Perhaps,” she said. “But my God simply asks that I try.”

And so I try, too. Mainly I try to have a little peace inside, which in some measure I can take out into the world with me. God knows the world needs it. I have carefully examined what happened on this trip to India, my attitude and my resentments toward the treatment of the poor. This is what I have chosen to remember in future trips: Accepting something doesn’t mean I have to like it. It simply allows me to accept reality as it actually is this minute, and then move into the solution, rather than obsessing on the problem. Today, I believe we all need solutions, so I choose the process, again and again, of surrendering, accepting, suiting up, and showing up … and letting go of the outcome.

Although sometimes the outcome lifts my heart.

After I returned home, I was shown a tape of Shahrukh Khan recording a powerful public service announcement for PSI/India. My little orphans Neelam and Komal had been invited to the taping, and they were clearly thrilled to be sitting with the most famous star in India. After he finished, Shahrukh called Neelam to stand beside him and announced that it was his great honor to present her with a scholarship from Ashley Judd and the Rai Foundation that would take care of her education all the way through a master’s degree. As she accepted the certificate, her serious, beautiful, shy face lit up like the rising sun.

Chapter 20

THE WHITE FLOWER OF RWANDA

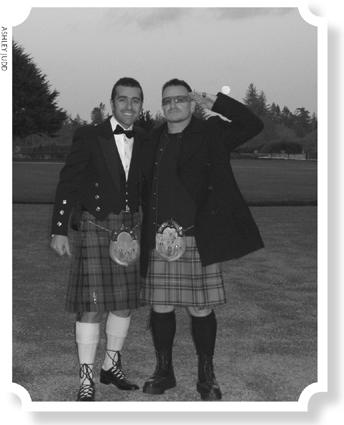

In the Highlands with my Scottish and Irish heroes, on my fortieth birthday.

Si tu me connaissais et si tu te connaissais vraiment, tu ne m’aurais pas tue.

(If you knew me, and if you really knew yourself, you would not have killed me.)

—FELICIE NTAGENGWA

celebrated my fortieth birthday—April 19, 2008—in the Scottish Highlands with Dario’s family and some dear friends, roaring with laughter, running a sack race, and winning the caber toss on the front lawn of Skibo Castle. Five days later, I was in a hotel room in Kigali, Rwanda, gazing out my window at the African sun setting in dazzling shades of orange and red. My last time on this continent, the original home of us all, I was so overwhelmed with emotion that I was nearly distraught. Everything, but everything, provoked a cry: My first African tree! My first African bird! My first African friend! I was returning to my cradle, and everything had the heightened drama of a seeker’s first pilgrimage. This time around, I was grateful to be emotionally sober (not somber—sober includes great mirth). Not that I was casual about this journey; far from it. I was simply … simpler. My gratitude, awe, respect, and even enthusiasm were more nuanced and subtle.

celebrated my fortieth birthday—April 19, 2008—in the Scottish Highlands with Dario’s family and some dear friends, roaring with laughter, running a sack race, and winning the caber toss on the front lawn of Skibo Castle. Five days later, I was in a hotel room in Kigali, Rwanda, gazing out my window at the African sun setting in dazzling shades of orange and red. My last time on this continent, the original home of us all, I was so overwhelmed with emotion that I was nearly distraught. Everything, but everything, provoked a cry: My first African tree! My first African bird! My first African friend! I was returning to my cradle, and everything had the heightened drama of a seeker’s first pilgrimage. This time around, I was grateful to be emotionally sober (not somber—sober includes great mirth). Not that I was casual about this journey; far from it. I was simply … simpler. My gratitude, awe, respect, and even enthusiasm were more nuanced and subtle.

There was tough work to be done on this trip. Rwanda is the most densely populated African country, with more than ten million people squeezed into an area the size of Maryland. It is also one of the poorest and most traumatized places on earth in the aftermath of a long series of genocides, culminating in the unspeakable genocide in 1994, in which eight hundred thousand people were murdered in the space of one hundred days and millions were driven from their homes. PSI is one of the NGOs that the Rwandan government has invited to help it build a community-based health care system as a foundation to lift its people out of abject poverty. As always, I was here to see our grassroots programs and others’ in action—particularly our child survival initiative called Five & Alive—to celebrate what works and the workers who do it, and to help carry the good news back to donors and policy makers that this remarkable country is lifting itself out of the ashes. For example, Rwanda has been outperforming most African countries in meeting its United Nations Millennium Development Goals, which provide a framework and set targets for poverty alleviation, education, child and maternal health, HIV and other disease eradication, and gender equity.

But there is no way to begin to understand the depths of Rwanda’s agony, or its soaring promise, without first plunging into the original heart of darkness. The genocide inescapably informs everything in this country and most certainly the public health mission here. It is the background, acknowledged if unspoken; it has set Rwanda’s stage.

So once again, as I did in Cambodia, I began this journey with a visit to a genocide memorial.

In an angular, sand-colored building surrounded by gardens and graves, the exhibits are divided into three parts: the roots of the genocide, the events of 1994, and the aftermath. The narrative format is so familiar to me: This is what I was. This is what happened. This is what I am now.

The first of three chambers was lined with black-and-white photos from Rwanda’s colonial past. First the Germans and then the Belgians claimed authority over this volcanic plateau southwest of Lake Victoria. According to the accompanying text, Rwandans identified themselves among eighteen clans, of which distinctions like Hutu and Tutsi were

occupational

and not tribal/ethnic at all. The colonists made up that all Tutsis were Nilotic pastoralists and Hutus were Bantu peasant farmers. One of the most enraging images was a 1932 photo of a Belgian priest, for God’s sake,

a priest

, measuring Rwandans’ heads and categorizing them ethnically for registration cards. Once the massacres began in 1994, these registration cards established the delivery system of death for nearly a million people.